At the Zoo

By Jessie Redmon Fauset

Annotations by Catherine Bowlin

MY mother said to me, “Now, mind, To animals be always kind; To every creature, bird or beast, Show courtesy, to say the least!” And then she took me to the Zoo, (She said she’d nothing else to do,) And showed me beasts of many styles, From prairie dogs to crocodiles. And take it from me, when I say I didn’t feel like getting gay, Or doing them a bit of harm. I wouldn’t touch them for a farm.

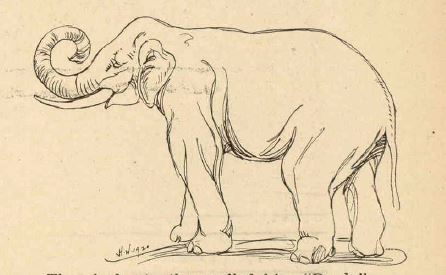

The elephant—they called him “Dunk,” Looked mild, but had a squirmy trunk. The panther and the wolf and bear, Threw into me an awful scare. (The bear looked pretty good, ‘tis true, But s’pose he started hugging you!) The foxes didn’t need their labels— I’d read of them in Aesop’s Fables!

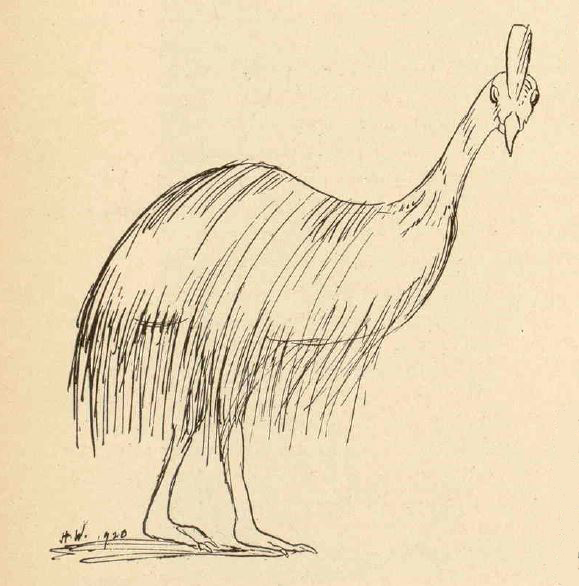

And next I saw a cassowary, [3] Who looked to me a bit contrary. “Of bird and beast, I’ve had my fill,” I said, “Please take me home, I’m ill. I promise to take your advice, You’ll never have to tell me twice.” But after I was home, in bed, I pulled the covers ’round my head, And saw those creatures at the Zoo, And thought, “No wonder that they’re blue, And look so cross and mean and mad, They have enough to make them sad. If I were locked up in a cage, I’d just be in an awful rage.

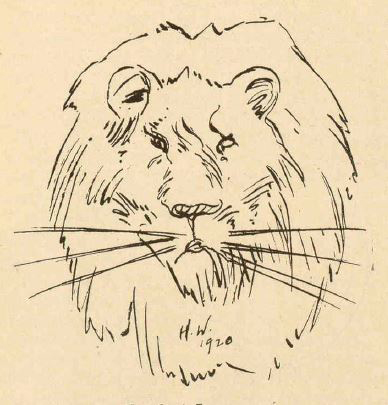

The lion was the first I saw, I just looked at his awful paw And thought, “I’ll never trouble you.” I thought that of the tiger, too; He was a striped all black and real bright yellow. But I could never play with him, His look just made my poor head swim.

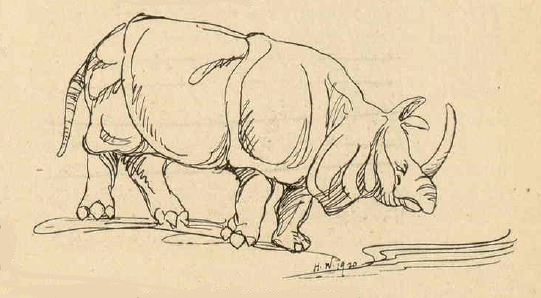

The hippopotamus and his friend, Rhinoceros, stood my hair on end. The python and the anaconda, Just made me grow of kindness, fonder.

I might have liked the dromedary–– [2] But oh, his manner was so airy! And, too, I danced the giraffe, His long neck really made me laugh. My mother said, “Come see the birds, They’re just too nice and sweet for words.” She showed me, first, a horned owl–– That really is an awful fowl! He blinked at me, as though to say, “I’ll bite your fingers. Get away!” And then I say a pelican, With long, sharp duck-bill. Well, he can Be sure I’ll never trouble him, And where he swims, I’ll never swim.

Perhaps they’ve children far away, Or friends who watch for them each day; Perhaps they dream at night, they’re free In forests green and shadowy; And then they wake to dull despair,— And little boys who poke and stare. Right then and there, I charged my mind, To be to all God’s creatures kind. And kind to them I’ll surely be If only they’ll be kind to me!

Fauset, Jessie. “At the Zoo.” The Brownies’ Book 1, no. 3 (March 1920): 85-86.

[2] An Arabian one-humped camel, especially one of the light and swift breed trained for riding or racing

[3] A huge flightless bird related to the emu, with a bare head and neck, a tall horny crest, and one or two colored wattles. It is native mainly to the forests of New Guinea.

Contexts

The goal of this poem’s child narrator is two-fold: to entertain and to teach “a moral lesson that animals have individual sensibilities and merit respect” (Kilcup 302, see full citation below). In the 1920s, American zoos were full of “exotic” species, and “Fauset’s poem both reflects Americans’ interest and questions how they treat nondomestic animals” (Kilcup 302).

Important to note also are the themes of captivity and freedom in this poem. Fauset comments on both the caged animals featured in the poem and the institution of slavery within the context of The Brownies’ Book.

Resources for Further Study

- Hanson, Elizabeth Anne. “Nature Civilized: A Cultural History of American Zoos, 1870-1940.” Dissertation, 1996.

- Horowitz, H. L. “Seeing Ourselves Through the Bars: A Historical Tour of American Zoos.” Landscape 25, no. 2 (1981): 12-19.

- Kilcup, Karen. Stronger, Truer, Bolder: American Children’s Writing, Nature, and the Environment. University of Georgia Press, 2021.