Battle of the Owls

By Joseph M. Poepoe (Kānaka Maoli)

Annotations by Jessica cory

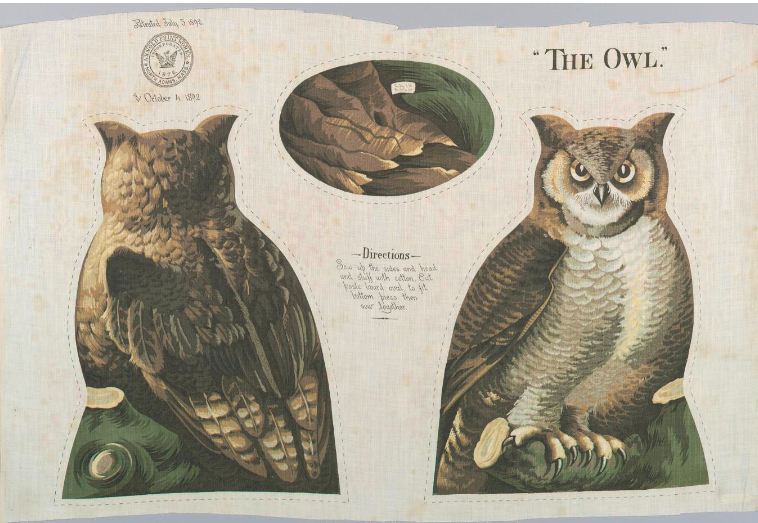

cotton), 1892, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, NY.

The following is a fair specimen of the animal myths current in ancient Hawaii, and illustrates the place held by the owl in Hawaiian mythology.

There lived a man named Kapoi, at Kahehuna, in Honolulu, who went one day to Kewalo to get some thatching for his house. On his way back he found some owl’s eggs, which he gathered together and brought home with him. In the evening he wrapped them in ti leaves[1] and was about to roast them in hot ashes, when an owl perched on the fence which surrounded his house and called out to him, “O Kapoi, give me my eggs!”

Kapoi asked the owl, “How many eggs had you?”

“Seven eggs,” replied the owl.

Kapoi then said, “Well, I wish to roast these eggs for my supper.”

The owl asked the second time for its eggs, and was answered by Kapoi in the same manner. Then said the owl, “O heartless Kapoi! why don’t you take pity on me? Give me my eggs.”

Kapoi then told the owl to come and take them.

The owl, having got the eggs, told Kapoi to build up a heiau, or temple, and instructed him to make an altar and call the temple by the name of Manua. Kapoi built the temple as directed; set kapu[2] days for its dedication, and placed the customary sacrifice on the altar.

News spread to the hearing of Kakuihewa, who was then King of Oahu, living at the time at Waikiki, that a certain man had kapued certain days for his heiau, and had already dedicated it. This King had made a law that whoever among his people should erect a heiau and kapu the same before the King had his temple kapued, that man should pay the penalty of death. Kapoi was thereupon seized, by the King’s orders, and led to the heiau of Kupalaha, at Waikiki.

That same day, the owl that had told Kapoi to erect a temple gathered all the owls from Lanai, Maui, Molokai, and Hawaii to one place at Kalapueo. [3] All those from the Koolau districts were assembled at Kanoniakapueo, [4] and those from Kauai and Niihau at Pueohulunui, near Moanalua.

It was decided by the King that Kapoi should be put to death on the day of Kane. [5] When that day came, at daybreak the owls left their places of rendezvous and covered the whole sky over Honolulu; and as the King’s servants seized Kapoi to put him to death, the owls flew at them, pecking them with their beaks and scratching them with their claws. Then and there was fought the battle between Kakuihewa’s people and the owls. At last the owls conquered, and Kapoi was released, the King acknowledging that his Akua (god) was a powerful one. From that time the owl has been recognized as one of the many deities venerated by the Hawaiian people.

Poepoe, Joseph m. “battle of the owls,” in hawaiian folk tales: a collection of native legends, ed. thomas g. thrum, 200-202. a.c. mcclurg & co., 1907.

[1] Ti leaves are leaves of Cordyline fruticosa, a tree that grows in the Pacific Islands. Its leaves are often used to wrap foods before cooking, similar to how corn husks are used for tamales.

[2] Kapu is a traditional code of conduct that governed many interpersonal, spiritual, and government interactions. By making “kapu days,” Kapoi would create holy days or dedicate them to a higher power. The word contemporarily means “taboo” or “avoid.”

[3] Situated beyond Diamond Head, a volcanic cone on Oahu.

[4] In Nuuanu Valley.

[5] When the moon is 27 days old.

Contexts

This story reminds us that while owls often signify death in some Native American tribes, particular tribal meanings or symbols are not universally true for all Indigenous peoples. It is also important to recognize that these are stories, not just myths. As stories, particularly Native Hawaiian stories (moʻolelos), there are many layers of meaning that a reader outside of that culture may not fully understand. For more information on moʻolelos, check out Kumakahi: Living Hawaiian Culture.

Resources for Further Study

- Joseph Poepoe’s extensive contributions to Kānaka Maoli (Native Hawaiian) intellectual life is well documented in Noenoe Silva’s (Kānaka Maoli) The Power of the Steel-Tipped Pen: Reconstructing Native Hawaiian Intellectual History.