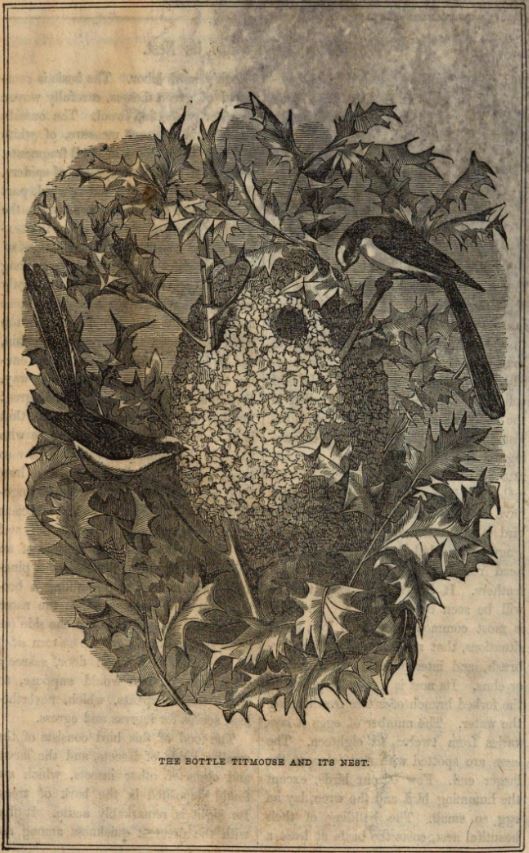

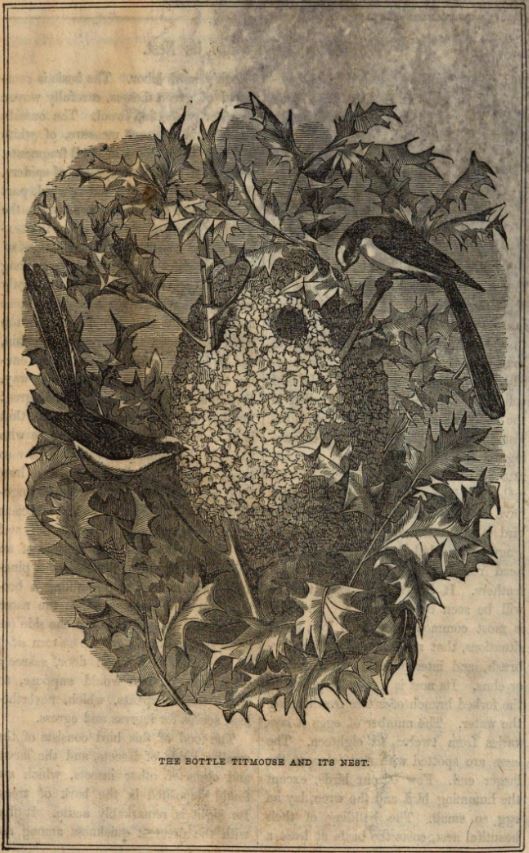

The Bottle Titmouse and its Nest

Author Unknown

Annotations by Jessica abell

There is a great deal of ingenuity displayed by many birds in their manner of building nests. But perhaps there is no bird which constructs one so curious as that species of the Parus vulgarly called Bottle Titmouse, or more familiarly, Bottle Tit. The bird is not a native of the latitude of New York, though it is found, I think, in the southern part of the United States. It will be interesting to the reader to know that it belongs to the same family with the snow-bird, that sings his “chick-a-de-de” so merrily during the winter. The little bird called the Bottle Titmouse, is called in the technical language of the ornithologist, the Parus Caudatus. The engraving on the preceding page is an accurate representation of the male and female of this species, with the nest they have so ingeniously built. This little bird is about five and a half inches in length. The bill is very short, and the head round and covered with rough feathers. It has a very long tail, as will be seen by the picture. The bird is most commonly found in low, moist situations, that are covered with underbrush, and interspersed with tall oaks or elms. Its nest is generally placed in the forked branch of a tree overhanging the water. The number of eggs it lays varies from twelve to eighteen. The eggs are spotted with rust color at the larger end. Few of our birds, except the humming bird and the wren; lay an egg so small. The building of their beautiful nest, costs the birds at least a month’s hard labor. The basis is composed of green mosses, carefully woven together with fine wool. The outside consists, in a great measure, of white and grey tree lichens, in small fragments, intermixed with the egg nests of spiders, from the size of a pea and upward, part of which are drawn out to assist in the weaving process—so that when the texture of the nest is stretched, portions of fine, gossamer-like threads appear along the fibres of the wool. Having neatly built and covered her nest with these materials, she thatches it on the top with tree moss, to keep out the rain, and to hide it from the eye of any enemy that may chance to come that way. Within she lines the nest with a great number of soft feathers—so many, that it is a matter of wonder to those who examine the beautiful structure, how so small a room can hold them, and how they can be laid so closely and ingeniously together, as to afford sufficient space for a bird with so long a tail, and so large a family. The nest is of an oblong shape, not unlike that of a pineapple, and somewhat resembling a bottle, from which circumstance the name of the bird was given. On one side (as some say, uniformly on the eastern side) of the nest, is a small door, scarcely large enough, one would suppose, to admit the occupants, which, nevertheless, serves for ingress and egress.

The food of this bird consists of the smaller kinds of insects, and the larvae and eggs of other insects, which are found deposited in the bark of trees. Its sight is remarkably acute. It flits with the greatest quickness among the branches of trees, while in pursuit of its food.

Knight[1], in his entertaining volume on the “Habits of Birds,” says he once saw a flock of Bottle Tits, just at dusk, in a noisy dispute as to the places where they were to roost respectively. That circumstance is not much to their credit, perhaps, and shows, that with all their intelligence and good qualities, they are not altogether destitute of foibles. The ground was covered with snow at the time—so says the observing man on whose authority the statement is made in Knight’s volume—and they were beginning, no doubt, to be cold, as the night approached, and were making preparations for passing the night in as warm a place as they could find. Then commenced a contest for the best spot, which seemed to be a hollow in the neighboring tree of large size. When they had all assembled on the under bough of the tree, they began to crowd together, fidgeting and wedging themselves between one another, evidently quarreling for the coziest corner.

AUTHOR UNKNOWN. “THE BOTTLE TITMOUSE AND ITS NEST.” THE YOUTH’S CABINET 4, NO. 4 (MARCH 1849): 104-5.

[1] Charles Knight’s The Domestic Habits of Birds was first published in London in 1833.

Contexts

The bottle titmouse is a member of the Parus genus of the Paridae family. This family includes titmice and chickadees. The bottle titmouse is more common in Europe than in the U.S. The author suggests that they can be found in the southern states but are not as common as other titmouse varieties, such as the bridled titmouse which resides in the southwest, the black-crested titmouse in the midwest and eastern and central Mexico, the juniper titmouse in the western U.S., the oak titmouse along the west coast, and tufted titmouse along the east coast.

Resources for Further Study

- The bottle titmouse is now known as the long-tailed tit (Aegithalos caudatus).

- Further information about the bottle titmouse, including its call