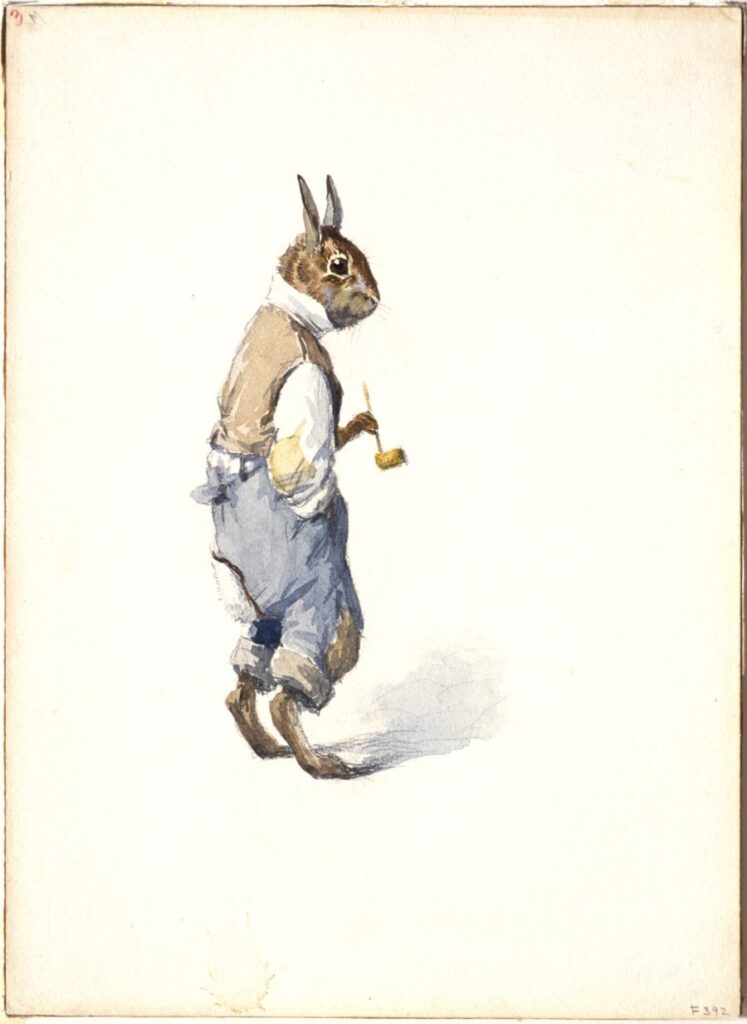

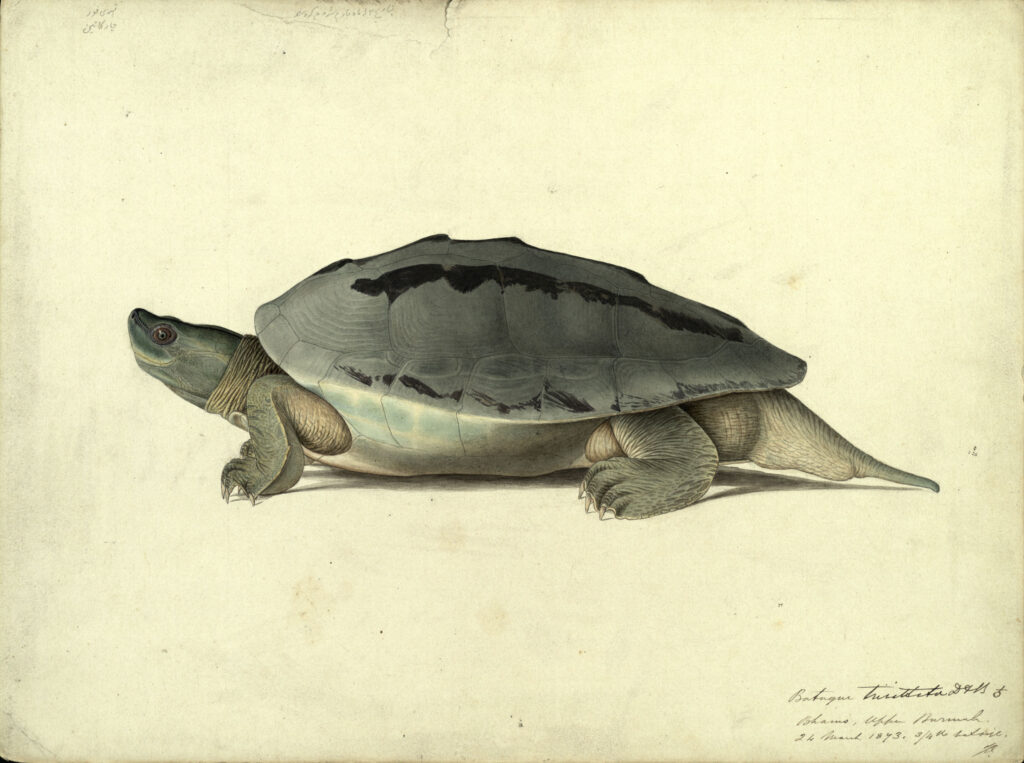

The Hare and the Tortoise

By Anonymous

Annotations by Rene Marzuk

(Original byline: A Negro fairy Folk-Tale From Uganda. Selected by M. N. Work.)[1]

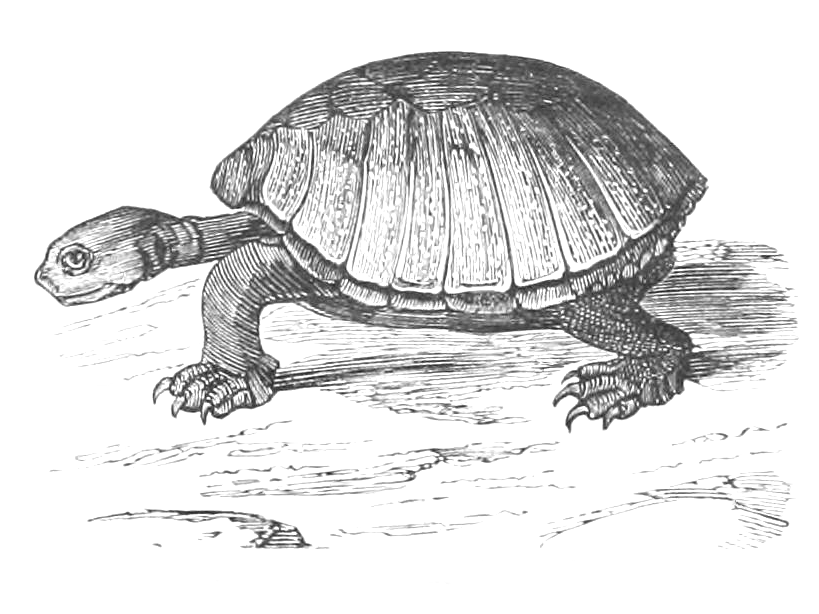

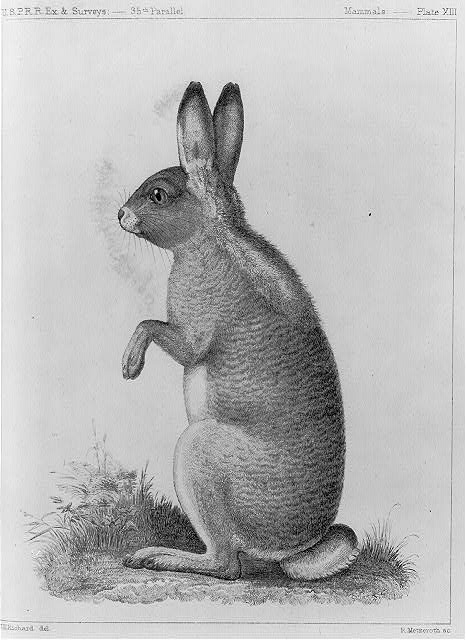

The hare and the tortoise were great friends. One day they decided to search for food. They went to an ant hill and dug a hole in it so as to trap the ants. The next day, as the time drew near for them to visit the hole, the hare said, “Why should an old fool like the tortoise share this feast with me? I can easily outwit him.” So he told his friends to wait in a quiet place for the tortoise and when he came by to seize him and carry him into the tall grass through which he would have great difficulty in pushing his way. His friends did as he requested. They waited and as the tortoise came by they caught him and carried him into the tall grass. In the meantime the hare ate all the ants he wanted and scampered off home.

The tortoise, after a long struggle, managed to get out of the grass. Tired and vexed he made his way to the ant hill, but found no food. He saw there, however, the footprints of the hare, and as it flashed upon him that he had been outwitted, he became angry and said, “Never mind, my cunning friend, I will get even with you for this.”

When he reached home the hare rushed out to meet him and said. “How thankful I am to see you safe. I feared you were killed. I only escaped myself by the merest chance. Three spears just missed me. We must never go back to that ant hill.”

“Have no fear”, said the tortoise. “Our enemies are not likely to come to the same spot again. It will be quite safe for us to go there another day.”

The tortoise, knowing that the selfish hare would sneak off alone to feast on the ants, arranged with his friends to catch the hare when he was busy eating. “Wait for him”, said the tortoise, “and when he has his head deep in the hole pounce upon him, but,” he added, “do not kill him.”

“Oh” said the friends, “we like hare’s meat; we want to eat him.”

“Very well”, said the tortoise, “but if you kill him quickly he will be tough. You must take him home, then make a pot ready half filled with fine oil and salt. Put the hare in the pot leaving a hole in the cover so that you may add cold water from time to time, for if you let the oil get hot you will completely spoil the hare. Be very careful, therefore, not to let it boil.”

The friends did exactly as they were told. They trapped the hare and carried him home. Then they put him in a pot with the best of oil, the proper amount of salt and placed the pot on the fire. Water was added occasionally through the hole made in the cover. After some hours, when all was thought to be ready, the friends, having washed their hands and nicely laid out the dishes, seated themselves expectantly. The pot was placed in their midst and the cover was withdrawn when hoy! presto! out jumped the hare, and to their horror, ran away. As he rushed into his house he found his comrade waiting.

“Dear me” said the tortoise, “Where have you been?”

“Alas! said the hare, “I have been in great danger. I nearly lost my life. I’ve been caught and cooked. It was only by a miracle that I escaped.”

As he said this he began to lick himself. The tortoise, noticing that a look of pleasure rapidly succeeded that of fright, went across to him and also began to lick.

“How delicious”, said he.

“Get away”, said the greedy hare. “You have not been in the pot or through all the trials I’ve been through. Keep off.”

The tortoise, feeling that his cunning had supplied the oil and salt, began to get angry.

“Let me have your shoulder and left side to lick?”

“I will not”, said the hare, more and more enjoying himself.

The tortoise, in great fury, left the house. He had not gone far before he met his angry friends coming to meet him

“What do you mean”? they asked.

“Through your advice we have lost not only the hare, but also our fine oil and salt. When we uncovered the pot the hare jumped out and ran off with the oil and salt all clinging to him.”

The tortoise, in his rage, lost every feeling of friendship for the hare and said, “I will tell you what to do. You arrange a dance and invite the hare and when he is dancing to your tom-tom seize him and this time kill him.”

The dance was arranged. The hare was invited and came. While he was dancing the friends suddenly seized him. To make sure that he would not escape this time they killed him, skinned him and cut him up.

Thus the hare, and because for once, was outwitted of his greediness, miserably perished.

“THE HARE AND THE TORTOISE.” THE CRISIS’ VOL. 12, NO. 6 (OCTOBER 1916): 271-72.

[1] In October of 1912, The Crisis published a nearly identical version of this short story: “Mr. Hare: A Story for Children.” The ending of the current version, selected by Monroe Nathan Work and published four years later in the same magazine, during World War I, is significantly less coddling than that of the 1912 version. While the 1916 hare dies, the one from 1912 survives the tortoise’s revenge.

Contexts

Starting in 1912, the October issues of The Crisis, the official magazine of the NAACP, were dedicated to children. A typical edition of these children’s numbers would contain a special editorial piece and two or three literary works specifically for children, while still including the serious pieces about contemporary issues with a focus on race that The Crisis was known for. These October numbers were sprinkled with children’s photographs sent in by the readers.

In his first editorial for the Children’s number in 1912, W. E. B. Du Bois wrote that “there is a sense in which all numbers and all words of a magazine of ideas myst point to the child—to that vast immortality and wide sweep and infinite possibility which the child represents.”

The success of The Crisis’ children’s number led to the standalone The Brownies’ Book, a monthly magazine for African American children that circulated from January 1920 to December 1921 under the editorship of Du Bois, Augustus Granville Dill, and Jessie Fauset.