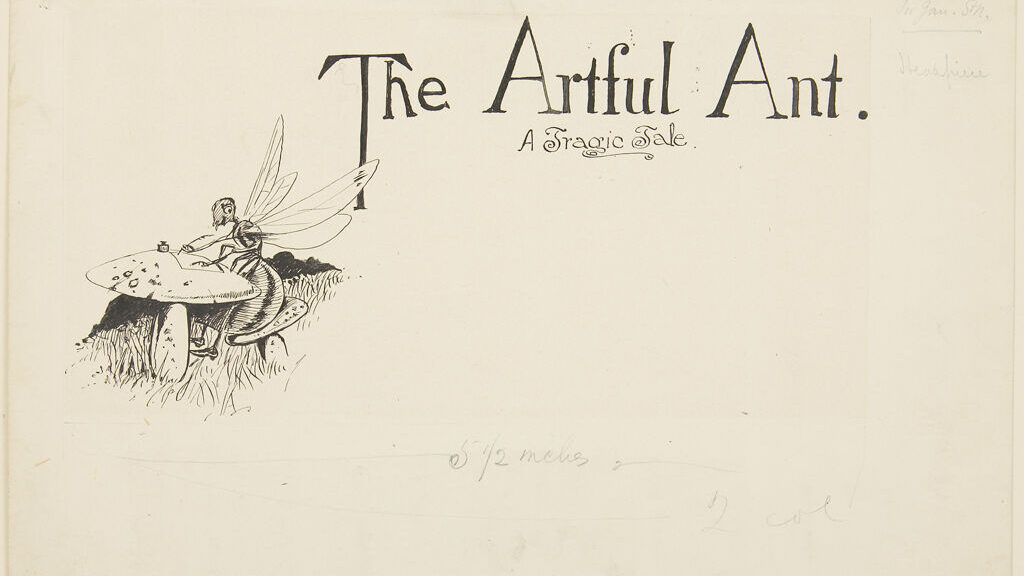

The Artful Ant

By Oliver Herford

Annotations by Rene Marzuk

Once on a time an artful Ant

Resolved to give a ball,

For tho’ in stature she was scant,

She was not what you'd call

A shy or bashful little Ant.

(She was not shy at all.)

She sent her invitations through

The forest far and wide,

To all the Birds and Beasts she knew,

And many more beside.

(“You never know what you can do,”

Said she, “until you 've tried.”)

Five-score acceptances came in

Faster than she could read.

Said she: “Dear me! I’d best begin

To stir myself indeed!”

(A pretty pickle she was in,

With five-score guests to feed!)

The artful Ant sat up all night,

A-thinking o’er and o’er,

How she could make from nothing, quite

Enough to feed five-score.

(Between ourselves I think she might

Have thought of that before.)

She thought, and thought, and thought all night,

And all the following day,

Till suddenly she struck a bright

Idea, which was— (but say!

Just what it was I am not quite

At liberty to say.)

Enough, that when the festal day

Came round, the Ant was seen

To smile in a peculiar way,

As if— (but you may glean

From seeing tragic actors play

The kind of smile I mean.)

From here and there and everywhere

The happy creatures came,

The Fish alone could not be there.

(And they were not to blame.

“They really could not stand the air,

But thanked her just the same.”)

The lion, bowing very low,

Said to the Ant: “I ne’er

Since Noah’s Ark remember so

Delightful an affair.”

(A pretty compliment, although

He really wasn’t there.)

They danced, and danced, and danced, and danced;

It was a jolly sight!

They pranced, and pranced, and pranced, and pranced,

Till it was nearly light!

And then their thoughts to supper chanced

To turn. (As well they might!)

Then said the Ant: “It’s only right

That supper should begin,

And if you will be so polite,

Pray take each other in.”

(The emphasis was very slight,

But rested on “Take in.”)

They needed not a second call,

They took the hint. Oh, —yes,

The largest guest “took in” the small,

The small “took in” the less,

The less “took in” the least of all.

(It was a great success!)

As for the rest—but why spin out

This narrative of woe?—

The Lion took them in about

As fast as they could go.

(And went home looking very stout,

And walking very slow.)

And when the Ant, not long ago,

Lost to all sense of shame,

Tried it again, I chance to know

That not one answer came.

(Save from the Fish, who “could not go,

But thanked her all the same.”)

HERFORD, OLIVER. “THE ARTFUL ANT,” IN ARTFUL ANTICKS, 4-9. NEW YORK: THE CENTURY CO., 1897.

Contexts

In a Life Magazine issue from November 1894, editor Robert Bridges noted that, in Artful Anticks, “when [Oliver Herford] makes rhymes about a kitten, a dormouse, a spider, or a crocodile, you are absolutely certain that he has put himself on such friendly terms with each animal that he is not only able to reveal the quirks of its mind, but draw a picture of them. That is why grown folks will get as much fun out of this book as children.”

Herford was a well-known poet, humorist writer, and illustrator.

Definitions from Oxford English Dictionary:

artful: Skilfully adapted for the accomplishment of a purpose; ingenious, clever. Hence: cunning, crafty, deceitful.

festal: Characteristic of a feast; (hence also) joyous or celebratory in tone; (of a person or group) in a festive or holiday mood.

five-score: Rarely used for “a hundred” (from Shakespeare).

Resources for Further Study

- Read more poems by Oliver Herford in All Poetry.

- Reusable Art features a growing collection of Oliver Herford’s illustrations