How Mr. Crocodile Got His Rough Back

By Julian Elihu Bagley

Annotations by josh benjamin

IT was a bleak November afternoon in New York City. To be more exact it was in Harlem. The snow was falling fast, and between the long row of high dwellings on 135th Street thousands of flakes were whirling, swirling about much the same as goose feathers would whirl if dumped from some high building into a rushing wind. The sun had long since hid his face, while the white fleecy clouds of the morning were fast changing into a cold, cold gray. It was too cold for the kiddies to go out. So in the high windows dozens of them could be seen watching the grown-ups hurrying along the street below. Occasionally some one tripped on the sidewalk. Then the youngsters could be seen tumbling back into their houses in an uproar of laughter.

Among these children was a little curly headed boy named Cless. But Cless had a different purpose from the other boys and girls. He was looking for the letter carrier. For every day Cless received some pretty post card from his father who was then working in a hotel at Palm Beach, Florida.

“What will it be today, and why doesn’t the mail man come on?” thought Cless. Finally the postman turned into 135th Street and made his way to the entrance of the building in which the little boy lived. Cless ran down to meet him. The postman handed him a card. On one side was Cless’ address, on the other a picture of a little colored boy riding a big crocodile. Cless was both disappointed and frightened.

This photo shows part of the Harlem neighborhood.

“Oo-ee! what an ugly thing this is,” he shouted as he turned and walked into the elevator.

“Let me see?” asked the elevator boy.

Cless handed him the card.

“Sure is ugly! And that’s the thing that eats little colored boys. See all them rough bumps on his back? Well, they are the toes of little colored babies sticking up under his skin. That’s Mister Crocodile,” concluded the elevator boy. “He used to have a smooth back before he began to eat little colored babies, but now it’s rough.”

Little Cless was very much frightened, and as soon as the elevator reached his floor he dashed out and went running to his apartment crying: “Granny! Granny! oh Granny, look what daddy sent me today—a big ugly crocodile! And I hear he eats little colored babies. Granny, is it true? Is it true, Granny?”

“Why certainly not, Cless. Who in the world told Granny’s little man such a story?”

“Elevator boy, Granny-elevator boy,” answered little Cless between sobs. And a little later he stopped crying and told his grandmother the story just as the elevator boy had told him.

“It’s no such a thing, it’s no such a thing,” said Granny. “Why don’t you know frogs were the real cause of crocodiles having rough backs?”

“How’s that, Granny? Please tell me—tell me quick, Granny, please,” begged little Cless.

“All right, I’ll tell you,” promised Granny, “for I certainly don’t want my little man scared to pieces with such ugly stories.” Now little Cless felt relieved. He hopped into Granny’s lap, huddled up close to her side and listened to her story of how the crocodile got his rough back.

“A long, long time ago,” she said, “in Africa, down on the River Nile there lived a fierce old crocodile. And this was the first crocodile in the world. Before him there were no others. Now this crocodile lived in a cluster of very thick brush, and, although there were many other animals in the swamp larger than he, he was king of them all. Every day some poor creature was seized and crushed to death between this cruel monster’s jaws. He was especially fond of frogs and used to crush dozens of them to death every day. Now the frogs could hop faster than the crocodile could run and he never caught them in a fair race. But he always got the best of them by hiding in the mud until some poor frog came paddling along and then he would nab him and crush him to death between his big saw-teeth. Of course this was easy, for at that time Mister Crocodile had a smooth, black back, and it was so much like the mud that the frogs could never tell where he was.

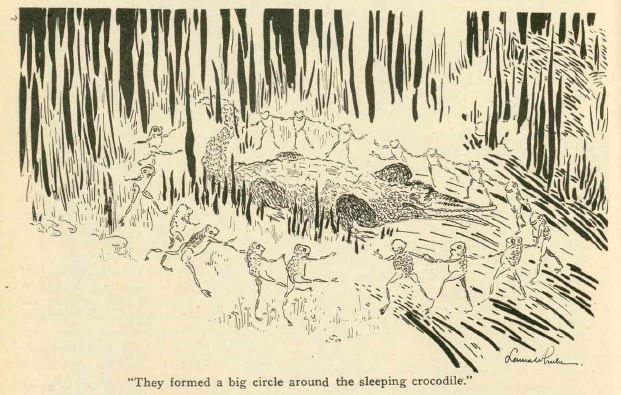

“But one day a happy thought struck Mister Bull Frog who was king of all the frogs in that swamp. He thought it would be a good idea to pile some lumps of mud on the crocodile’s back, and then the frogs could always tell where he was. This plan was gladly accepted by all the frogs in the swamp. So the next time the crocodile crawled into the mud to take his winter nap, Mister Bull Frog and all the other frogs went to the place where the monster lay and daubed a thousand little piles of mud on his back. And when they had finished they could see him from almost any part of the swamp. Now they knew they were safe. How happy they were! They all joined hands, formed a big circle around the sleeping crocodile, and while Mister Bull Frog beat time on his knee the others shouted this jingle so hard that their little throats puffed out like a rubber ball:

‘Ho, Mister Crocodile, king of the Nile,

We got you fixed for a long, long while.

Deedle dum, dum, dum, deedle dum day,

Makes no difference what you say!’

“They shouted this jingle over and over again. And the last time they sang it Mister Bull Frog got so happy he stopped beating time, jumped up in the air, cut a step or two, then joined in the chorus with his big heavy voice:

‘Honkey-tonkey tunk, tunk, tink tunk tunk!

Honkey-tonkey, tunk, tunk, tink tunk tunk!’

And when all the singing and dancing were over the little frogs went home.

“But Mister Bull Frog chose to stay and watch the crocodile. All winter long the crocodile lay in the mud. Nevertheless the Bull Frog kept a close watch over him. Each day the lumps of mud that the frogs had stuck on his back were growing harder and harder.

“At last spring came. The sleepy creature awoke and immediately began to shake his back and flop his tail. But the more he did this the madder he became. Finally he was just whirling ’round and ’round in the mud, biting himself on the tail and groaning, ‘Honk! honk! honk!’ But the lumps of mud had done their work. They were there to stay. And finding it of no use to wiggle he crawled out on the bank of the river and began to look for something to eat. Nothing could be found on the shore, however, so he slipped back into the muddy water to see if he could catch some frogs. In this he failed, for no longer could he hide himself. No matter how much his skin looked like the mud, the little frogs could always tell where he lay by his rough back.

“So ever since that day little frogs have lived in perfect safety along the banks of the River Nile or any other place so far as crocodiles are concerned. And as for Mister Crocodile himself, he has gone on and on even down to this day with his rough scaly back. And this is how he got it Cless,” ended Granny, “and not by eating little colored babies.”

Digital Public Library of America.

Little Cless had followed every word of Granny’s with eager interest. Now he smiled a smile of relief, thanked her for the story, jumped from her lap and skipped out to join the happy group of little children who were still peeping into the street from their windows. Here Cless showed his crocodile to as many children as were close enough to see it. And to those who were nearest he told the story over and over again of how the crocodile got his rough back.

Bagley, Julian elihu. “How Mr. crocodile got his rough back.” The brownies’ book 1, No. 11 (November 1920): 323-25.

Contexts

This issue of The Brownies’ Book was published the same month as the first U.S. presidential election following World War I, which was influenced by the postwar economic recession and reactions to the policies of Woodrow Wilson, who was not nominated for a third term despite requesting the Democratic candidacy. Bagley had served during the war in the U.S. Army, which still featured segregated units.

The mention of Palm Beach ties this story to Bagley’s home state (where he would set his later book of animal folktales, Candle-Lighting Time in Bodilalee), while the mention of Harlem (a district that makes up a large part of northern Manhattan, New York City) is also significant. The Harlem Renaissance was growing, with an influx of returning soldiers and people relocating from around the country, contributing to the new culture. Residences on 135th St. were prominent destinations due to their ownership by African-American realtors.

The story is in the tradition of African-American folktales, which sought to preserve the storytelling traditions that were an important piece of heritage for many Americans. As Henry Louis Gates, Jr. notes in his foreword to The Annotated American Folktales [1], “not only did the captured Africans bring their languages, their music, their gods, and many other salient features of their cultures along with them, they quickly learned to communicate with each other across language barriers not only on their own plantations and other sites of enslavement but across longer distances as well. And the telling and retelling of folktales from Africa, as well as those retold and, in the process, creatively reinvented from African and European sources, along with those invented on the spot, were crucial components of identity-formation and psychic survival under the harshest of circumstances, key aspects in the shaping of an ‘African American’ cultures, a culture built on both African and European Old World foundations, yet one original and new.”

In her introduction to the same book, Maria Tatar explains that “folk narratives, told in the fields and in cabins, are in many ways a significant part of an American vernacular tradition that preserved collective mother wit and wisdom in the form of story. Sometimes they were heard in snatches of conversation or in other bits and pieces of talk, and sometimes they were performed formally as a story—for young and old, rich and poor, men and women, black and white, slaves and masters.”

Resources for Further Study

- This story is included in The Annotated African American Folktales, edited by Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Maria Tatar.

- A brief story on the genesis of The Annotated African American Folktales.

Contemporary Connections

Visitors to 135th St. in Harlem can follow the walk of fame, a series of diamond-shaped plaques set in the sidewalk to commemorate the neighborhood’s famous and influential residents.

[1] Gates, Henry Louis, and Maria Tatar. The Annotated African American Folktales. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W. W. Norton & Company, 2018.