In Flanders Fields: An Echo[1]

By Orlando C. W. Taylor

Annotations by Rene Marzuk

In Flanders fields the poppies blow[2] Between the crosses, row on row That mark the graves where black men lie;[3] Their souls, long wafted to the sky, Look down upon the earth below. E’en while we mourn their loss, we see Their brothers hanged upon a tree By whom they saved. Their pain fraught cry[4] Mounts up to those who stand on high, And watch the scarlet flowered sea In Flanders fields. In Flanders Fields they shall not sleep! No! For their murdered kin they keep A vigil through the day and night, 'Til God Himself shall snatch from sight Such scenes as make our heroes weep In Flanders fields.

TAYLOR, ORLANDO C. W. “IN FLANDERS FIELDS,” IN THE DUNBAR SPEAKER AND ENTERTAINER, ED. ALICE MOORE DUNBAR-NELSON, 144. NAPERVILLE, ILL: J. L. NICHOLS & CO., 1920.

[1] Taylor’s poem references “In Flanders Fields,” a famous memorial poem written by Canadian officer John McCrae during the First World War. McCrae’s original poem helped establish the red poppy as the flower of remembrance.

[2] Flanders Fields, which spans across sections of Belgium and France, was the site of several World War I battlefields.

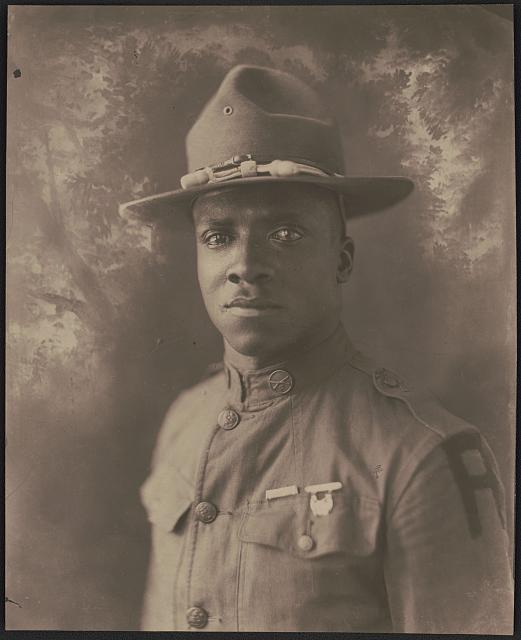

[3] According to the U.S. Department of Defense, more than 380,000 African-Americans served in the Army during World War I.

[4] During 1882 and 1968, 4,743 people were lynched in the U.S. Of them, 3,446 were African Americans.

Contexts

The Dunbar Speaker and Entertainer‘s dedication reads: “To the children of the race which is herein celebrated, this book is dedicated, that they may read and learn about their own people.” In the foreword, Leslie Pinckney Hill, an African American educator, writer, and community leader who graduated from Harvard University in 1903, criticizes the one-sidedness of prevailing reading courses: “In vain may you search their pages—those pages upon which all our reading has been founded—for anything other than a patronizing view of that vast, brooding world of colored folk—yellow, black and brown—which comprises by far the largest portion of the human family.” Hill further writes that Alice Dunbar-Nelson’s book seeks to prove “that the white man has no fine quality, either by heart or mind, which is not shared by his black brother.”

Think of reading this poem out loud. Elocution (or public speaking) was a highly valued and widely taught skill in nineteenth-century America. In her introduction to the Dunbar Speaker, Alice Dunbar-Nelson offers some advice: “Before you begin to learn anything to recite, first read it over and find out if it fires you with enthusiasm. If it does, make it a part of yourself, put yourself in the place of the speaker whose words you are memorizing, get on fire with the thought, the sentiment, the emotion-then throw yourself into it in your endeavor to make others feel as you feel, see as you see, understand what you understand. Lose yourself, free yourself from physical consciousness, forget that those in front of you are a part of an audience, think of them as some persons whom you must make understand what is thrilling you–and you will be a great speaker.”

Resources for Further Study

- Michael E. Ruane, “African American World War I Soldiers Served as a Time Racism Was Rampant in the U.S.,” Washington Post, September 22, 2017.

- Lynching in America is an interactive website structured around Equal Justice Initiative (EJI)’s comprehensive report Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror.

- Clinton Briggs, an African American War World I veteran, was chained to a tree and shot by a group of white men in Arkansas in 1919 after replying that he lived in a free man’s country when a white woman told him that he was not allowed to walk on the sidewalk. His story is one among many.