Miss Katy-did and Miss Cricket

By Harriet Beecher Stowe

Annotations by karen kilcup

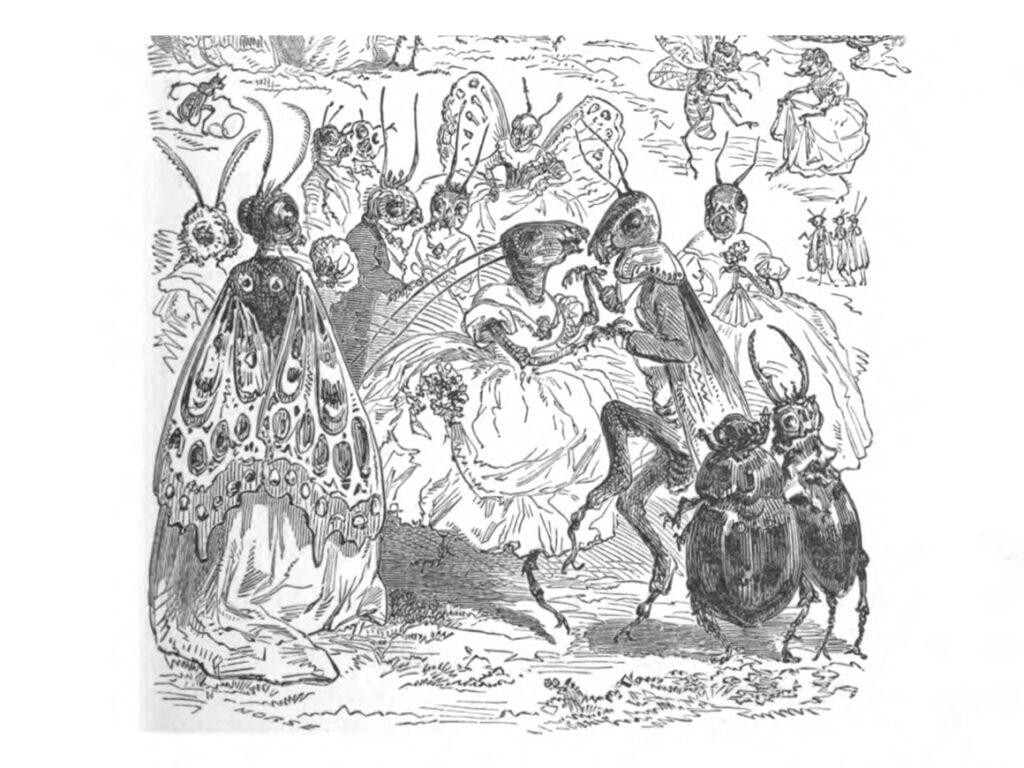

By H.L. Stephens, Harry Fenn, and A.R. Waud. Public domain.

Miss Katy-did sat on the branch of a flowering Azalia, in her best suit of fine green and silver, with wings of point-lace from Mother Nature’s finest web. [1]

Miss Katy was in the very highest possible spirits, because her gallant cousin, Colonel Katy-did, had looked in to make her a morning visit. It was a fine morning, too, which goes for as much among the Katy-dids as among men and women. It was, in fact, a morning that Miss Katy thought must have been made on purpose for her to enjoy herself in. There had been a patter of rain the night before, which had kept the leaves awake talking to each other till nearly morning; but by dawn the small winds had blown brisk little puffs, and whisked the heavens clear and bright with their tiny wings, as you have seen Susan clear away the cobwebs in your mamma’s parlor; and so now there were only left a thousand blinking, burning water-drops, hanging like convex mirrors [2] at the end of each leaf, and Miss Katy admired herself in each one.

“Certainly I am a pretty creature,” she said to herself; and when the gallant Colonel said something about being dazzled by her beauty, she only tossed her head and took it as quite a matter of course.

“The fact is, my dear Colonel,” she said, “I am thinking of giving a party, and you must help me to make out the lists.”

“My dear, you make me the happiest of Katy-dids.”

Now,” said Miss Katy-did, drawing an azalia-leaf towards her, “let us see–whom shall we have? The Fireflies, of course; everybody wants them, they are so brilliant,–a little unsteady, to be sure, but quite in the higher circles.”[3]

“Yes, we must have the Fireflies,” echoed the Colonel.

“Well, then,–and the Butterflies and the Moths. Now, there’s a trouble. There’s such an everlasting tribe of those Moths; and if you invite dull people they’re always sure all to come, every one of them. Still, if you have the Butterflies, you can’t leave out the Moths.” [4]

“Old Mrs. Moth has been laid up lately with a gastric fever, and that may keep two or three of the Misses Moth at home,” said the Colonel.

“What ever could give the old lady such a turn?” said Miss Katy. “I thought she never was sick.”

“I suspect it’s high living. I understand she and her family ate up a whole ermine cape last month, and it disagreed with them.”

“For my part, I can’t conceive how the Moths can live as they do,” said Miss Katy with a face of disgust. Why, I could no more eat worsted and fur, as they do—-.”

“That is quite evident from the fairy-like delicacy of your appearance,” said the Colonel. “One can see that nothing so gross and material has ever entered into your system.”

“I’m sure,” said Miss Katy, “mamma says she doesn’t know what does keep me alive; half a dewdrop and a little bit of the nicest part of a rose-leaf, I assure you, often last me for a day. But we are forgetting our list. Let’s see,–the Fireflies, Butterflies, Moths. The Bees must come, I suppose.”

“The Bees are a worthy family,” said the Colonel.

“Worthy enough, but dreadfully hum-drum,” said Miss Katy. “They never talk about anything but honey and housekeeping; still, they are a class of people one cannot neglect.”

“Well, then, there are the Bumble-Bees.” [3]

“Oh, I doat on them! General Bumble is one of the most dashing, brilliant fellows of the day.”

“I think he is shockingly corpulent,” said Colonel Katy-did, not at all pleased to hear him praised;–“don’t you?”

“I don’t know but he is a little stout,” said Miss Katy; “but so distinguished and elegant in his manners,–something quite martial and breezy about him.”

“Well, if you invite the Bumble-Bees, you must have the Hornets.” [4]

“Those spiteful Hornets,–I detest them!”

“Nevertheless, dear Miss Katy, one does not like to offend the Hornets.”

“No, one can’t. There are those five Misses Hornet,–dreadful old maids!–as full of spite as they can live. You may be sure they will every one come, and be looking about to make spiteful remarks. Put down the Hornets, though.”

“How about the Mosquitos?” said the Colonel.

“Those horrid Mosquitos,–they are dreadfully plebeian! Can’t one cut them?” [6]

“Well, dear Miss Katy,” said the Colonel, “if you ask my candid opinion as a friend, I should say not. There’s young Mosquito, who graduated last year, has gone into literature, and is connected with some of our leading papers, and they say he carries the sharpest pen of all the writers. It won’t do to offend him.”

“And so I suppose we must have his old aunts, and all six of his sisters, and all his dreadfully common relations.”

“It is a pity,” said the Colonel, “but one must pay one’s tax to society.”

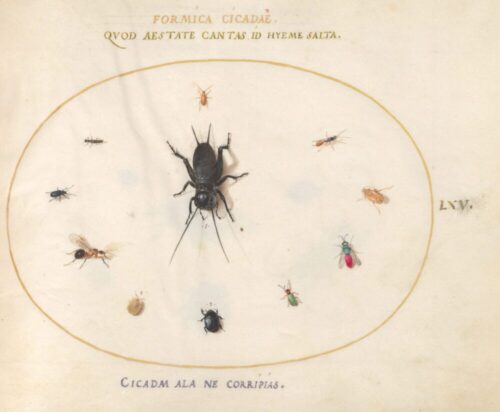

Courtesy National Gallery of Art.

Just at this moment the conference was interrupted by a visitor, Miss Keziah Cricket, who came in with her work-bag on her arm to ask a subscription for a poor family of Ants who had just had their house hoed up in clearing the garden-walks.

“How stupid of them!” said Katy, “not to know any better than to put their house in the garden-walk; that’s just like those Ants!”[7]

“Well, they are in great trouble; all their stores destroyed, and their father killed,–quite cut in two by a hoe.”

“How very shocking! I don’t like to hear such disagreeable things,–it affects my nerves terribly. Well, I’m sure I haven’t anything to give. Mamma said yesterday she was sure she did n’t know how our bills were to be paid,–and there’s my green satin with point-lace yet to come home.” And Miss Katy-did shrugged her shoulders and affected to be very busy with Colonel Katy-did, in just the way that young ladies sometimes do when they wish to signify to visitors that they had better leave.

Little Miss Cricket perceived how the case stood, and so hopped briskly off, without giving herself even time to be offended. “Poor extravagant little thing!” she said to herself, “it was hardly worth while to ask her.”

Pray, shall you invite the Crickets?” said Colonel Katy-did. [8]

“Who? I? Why, Colonel, what a question! Invite the Crickets? Of what can you be thinking?”

“And shall you not ask the Locusts, or the Grasshoppers?”

“Certainly. The Locusts, of course,–a very old and distinguished family; and the Grasshoppers are pretty well, and ought to be asked. But we must draw a line somewhere,–and the Crickets! why, it’s shocking even to think of!”

“I thought they were nice, respectable people.”

“O, perfectly nice and respectable,–very good people, in fact, so far as that goes. But then you must see the difficulty.”

“My dear cousin, I am afraid you must explain.”

“Why, their color, to be sure. Don’t you see?”

“Oh!” said the Colonel. “That’s it, is it? Excuse me, but I have been living in France, where these distinctions are wholly unknown, and I have not yet got myself in the train of fashionable ideas here.” [9]

“Well, then, let me teach you,” said Miss Katy. “You know we republicans go for no distinctions except those created by Nature herself, and we found our rank upon color, because that is clearly a thing that none has any hand in but our Maker. You see?”

“Yes; but who decides what color shall be the reigning color”?

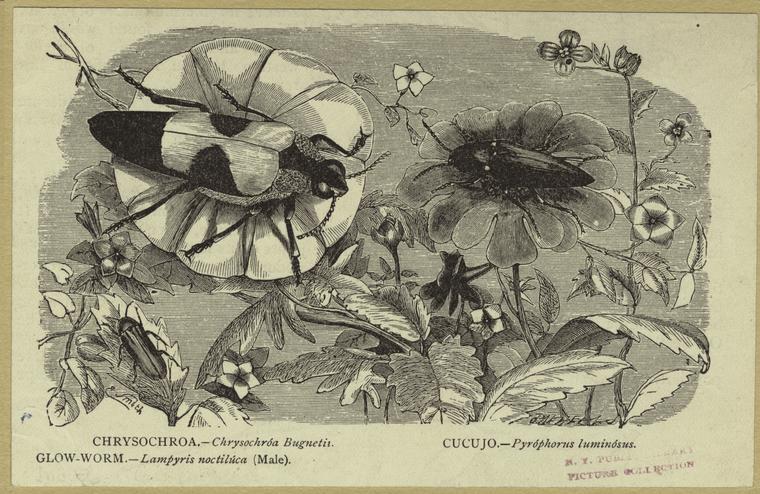

Public domain.

“I’m surprised to hear the question! The only true color–the only proper one–is our color, to be sure. A lovely pea-green is the precise shade on which to found aristocratic distinction. But then we are liberal;–we associate with the Moths, who are gray; with the Butterflies, who are blue-and-gold-colored; with the Grasshoppers, yellow and brown;–and society would become dreadfully mixed if it were not fortunately ordered that the Crickets are black as jet. The fact is, that a class to be looked down upon is necessary to all elegant society, and if the Crickets were not black, we could not keep them down, because, as everybody knows, they are often a great deal cleverer than we are. They have a vast talent for music and dancing; they are very quick at learning, and would be getting to the very top of the ladder if we once allowed them to climb. But their being black is a convenience,–because, as long as we are green and they black, we have a superiority that can never be taken from us. Don’t you see now?”

“O yes, I see exactly,” said the Colonel.

“Now that Keziah Cricket, who just came in here, is quite a musician, and her old father plays the violin beautifully;–by the way, we might engage him for our orchestra.”

And so Miss Katy’s ball came off, and the performers kept it up from sun-down till daybreak, so that it seemed as if every leaf in the forest were alive. The Katy-dids, and the Mosquitos, and the Locusts, and a full orchestra of Crickets made the air perfectly vibrate, insomuch that old Parson Too-Whit, who was preaching a Thursday evening lecture to a very small audience, announced to his hearers that he should certainly write a discourse against dancing for the next weekly occasion. [10]

The good Doctor was even with his word in the matter, and gave out some very sonorous discourses, [11] without in the least stopping the round of gayeties kept up by these dissipated Katy-dids, which ran on, night after night, till the celebrated Jack Frost epidemic, which occurred somewhere about the first of September. [12]

Public domain.

Poor Miss Katy, with her flimsy green satin and point-lace, was one of the first victims, and fell from the bough in company with a sad shower of last year’s leaves. The worthy Cricket family, however, avoided Jack Frost by emigrating in time to the chimney-corner of a nice little cottage that had been built in the wood that summer. [13]

There good old Mr. and Mrs. Cricket, with sprightly Miss Keziah and her brothers and sisters, found a warm and welcome home; and when the storm howled without, and lashed the poor naked trees, the Crickets on the warm hearth would chirp out cheery welcome to papa as he came in from the snowy path, or mamma as she sat at her work-basket. [14]

“Cheep, cheep, cheep!” little Freddy would say. “Mamma, who is it say ‘cheep’?”

“Dear Freddy, it’s our own dear little cricket, who loves us and comes to sing to us when the snow is on the ground.”

So when poor Miss Katy-did’s satin and lace were all swept away, the warm home-talents of the Crickets made for them a welcome refuge.

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s “Miss Katy-Did and Miss Cricket.” First published in Our Young Folks 2, no. 5 (May 1866): 286-93. Collected in Stowe’s single-author volume Queer Little People (Boston: Fields, Osgood, 1869), 39-47.

[1] Katydid: A type of large green American grasshopper. Azalia: Stowe references the flowering azalea, a type of rhododendron. Point-lace: a very fine lace made using only a needle and thread (OED).

[2] Convex Mirror: A mirror that curves “outward like the exterior of a sphere.”

[3] Fireflies blink intermittently for courtship purposes and can fly very high.

[4] Butterflies and moths belong to the same insect family; clothes moths’ larvae feed on wool, fur, and feathers.

[5] Bees are “champion pollinators,” and according to the U.S. Forest Service, there are “over 4000 species of native bees.” Bumblebees are “common native bees and important pollinators in most areas of North America.” Hornets, a type of stinging wasp, are also important pollinators.

[6] Stowe envisages mosquitos as society newspaper critics; she also jokes about their numerousness. Plebeian: “one of the common people”; ordinary, with the implication of crudeness.

[7] Katy’s visitor is named after the biblical Kezia, Job’s second daughter. She is associated with beauty and (indirectly) equality, because Job gave his daughters an inheritance equal to that which he gave his sons.

Ants are “social insects that are great lovers of nectar”–like many that Stowe mentions, they are important pollinators. They often gather around gardens and paths.

[8] Stowe probably references the black field cricket, an American species, rather than the house cricket, which was introduced from Europe. The reference below to crickets’ musical ability mirrors the “musical ability of the male.”

[9] France was known for its relative openness to racial difference. The country had abolished slavery in 1794, the earliest nation to do so, but Napoleon reinstated that horror in France’s colonies. The French antislavery movement finally succeeded in 1848. In “Collective Degradation,” historian Geroge M. Frederickson comments that “Post-1848 France did not have a domestic color line for the simple reason that no significant black population had been allowed to develop there” (11). See also Krishan Kumar, “English and French National Identity,” esp. 422.

[10] Opposition to dancing in the U.S. began with the Puritans, who believed it promoted sinfulness; in the nineteenth century, some traditional ministers continued condemning the practice.

[11] Sonorous: loud and impressive. Discourse: a formal talk; here, suggesting a sermon.

[12] Jack Frost: the personification of winter, which Stowe signifies by the first date of a hard frost in her native New England. The figure, also associated with Old Man Winter, appeared widely in American literature and popular media.

[13] Stowe is probably referencing Charles Dickens’s novella, A Cricket on the Hearth, which he published for Christmas 1845. This love story features a cricket that protects the family. Contemporary companies sell brass hearth crickets as emblems of good fortune.

[14] Here the story’s focus changes from the insects to the human family that live with the Cricket family; “little Freddy” is the son.

Contexts

Many of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s contemporaries credited her most famous work, Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), with propelling the abolitionist movement and helping end slavery. That bestselling novel, which sold thousands of copies on its first day and more than 300,000 during its first year in print, has long been controversial, particularly among African Americans, for its racist depiction of its hero. In 1949, James Baldwin published an essay titled “Everybody’s Protest Novel,” attacking the book, and in 2016, Nobel Prize winner Toni Morrison critiqued how the book romanticized and sanitized slavery. Scholars have shown how Uncle Tom’s Cabin retold the real-life story of Josiah Henson, a formerly enslaved African American who escaped to Canada and lived to the age of 93. More recent scholars such as Henry Louis Gates, Jr. have urged that we rethink our views on the novel.

Like most nineteenth-century American writers, including Nathaniel Hawthorne, Stowe wrote for children; this writing is unfamiliar to most readers. The appearance of “Miss Katy-did and Miss Cricket” in Our Young Folks reveals her importance to American parents and children. Published only a year after the Civil War had ended, the story uses insects to teach both natural history and moral values. Stowe anthropomorphizes the insects, attributing to them characteristics that mirror how humans see them: thus, the Mosquitos are “sharp,” the Moths eat furs and wool; the Bees are “corpulent,” and the Hornets are “spiteful.” Miss Katy-did’s conversation with Colonel Katy-did exposes how arbitrary American social and racial hierarchies were. Here the author sharply criticizes those who consider themselves “republicans” and yet are more interested in fashion and associating with the “right” members of society than in fostering an egalitarian ethos. Those people included Northern abolitionists. Queer Little People, the book in which Stowe collected “Miss-Katy-did,” contains several stories that focus on animal welfare, including “Aunt Esther’s Rules.”

Stowe’s contemporaries eagerly shared information about insects—pests, pollinators, and beneficial insects generally. Bees were especially important, and they figured regularly in nineteenth-century American children’s literature.

Resources for Further Study

- On Stowe and Uncle Tom’s Cabin:

Brock, Jared. “The Story of Josiah Henson, the Real Inspiration for ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” Smithsonian, May 16, 2018.

Brown, Lois. “African American Responses to Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” Uncle Tom’s Cabin and American Culture. Stephen Railton and the University of Virginia.

Gordon-Reed, Annette. “‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin’ and the Art of Persuasion: How Harriet Beecher Stowe Helped Precipitate the Civil War.” New Yorker, June 6, 2011.

Henson, Josiah. The Life of Josiah Henson, Formerly a Slave, Now an Inhabitant of Canada, as Narrated by Himself. Boston: Arthur D. Phelps, 1849. Documenting the American South. UNC-Chapel Hill, 2001.

Jay, Gregory S. Introduction. White Writers, Race Matters: Fictions of Racial Liberalism from Stowe to Stockett. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Morrison, Toni. “Romancing Slavery.” In The Origin of Others (The Charles Eliot Norton Lectures). Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2017. Chapter 1.

Radsken, Jill. “Slavery’s Chilling Shadow.” The Harvard Gazette, March 3, 2016.

Thompson, Cheryl. “Uncle Tom’s Cabin Historic Site and Creolization: The Material and Visual Culture of Archival Memory.” African and Black Diaspora: An International Journal 12, no. 3 (June 2019): 304-19.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin Reconsidered: A Conversation with Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Hollis Robbins, and Margo Jefferson, Moderated by Thelma Golden. New York Public Library, November 29, 2006. Transcript. Audio.

“Why African Americans Loathe ‘Uncle Tom.’” In Character, NPR, July 30, 2008.

Winks, Robin. “The Making of a Fugitive Slave Narrative: Josiah Henson and Uncle Tom: A Case Study.” In The Slave’s Narrative, ed. Charles T. Davis and Henry Louis Gates, Jr., 112-46. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985.

- On Stowe and children’s writing:

Fielder, Brigitte Nicole. “Animal Humanism: Race, Species, and Affective Kinship in Nineteenth-Century Abolitionism.” American Quarterly 65, no. 3 (September 2013): 487-514.

Ginsberg, Lesley. “ ‘I Am Your Slave for Love’: Race, Sentimentality, and Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Fiction for Children.” In Enterprising Youth: Social Values and Acculturation in Nineteenth-Century American Children’s Literature, ed. Monika Elbert, 97-113. New York: Routledge, 2015.

Kilcup, Karen L. Stronger, Truer, Bolder: American Children’s Writing, Nature, and the Environment. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2021. Chapter 3.Uncle Tom as Children’s Book. Uncle Tom’s Cabin and American Culture. Stephen Railton and the University of Virginia.

Pedagogy

“Teacher Resources,” Celebrating Wildflowers, U.S. Forest Service [this page links to information on pollinators]

Biography of Stowe from the National Women’s History Museum

Biography of Stowe from the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center in Hartford, Connecticut (lots of information on this site!)

Biography of Stowe from the University of Pennsylvania digital library

“Connect the Past to the Present.” Harriet Beecher Stowe Center. Hartford, Connecticut.

“Harriet Beecher Stowe | Author and Abolitionist.” PBS Learning Media, NHPBS. [Grades 3-7, 13+. Lesson Plan.]

“Harriet Beecher Stowe: Uncle Tom’s Cabin | The Abolitionists.” PBS Learning Media, NHPBS. [Grades 8-12. Video]

Stowe’s Ohio home and the Underground Railroad

Stowe’s Maine home and Uncle Tom’s Cabin

Stowe’s publications in the Atlantic Monthly (links), including one on Sojourner Truth

“Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” American Experience. PBS, January 8, 2013.

Perrin, Dr. Tom. “Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Popular Culture: Web Sites.” Houghton Memorial Library, Huntingdon College, 2012.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin Told to Children. Kid Zone! National Center on Improving Literacy.

Contemporary Connections

Holly L. Derr comments that “Orange Is the New Black”s Crazy Eyes and Miley Cyrus’s VMA Performance recall the Harriet Beecher Stowe classic, even if their creators didn’t intend to.”

Derr, Holly L. “The Pervading Influence of Uncle Tom’s Cabin in Pop Culture.” The Atlantic, September 4, 2013.

Eaton, Dr. Alan T. “Beneficial Insects in New Hampshire Farms & Gardens.” UNH Cooperative Extension Service, April 2017.

“The Legend of the Hearth Cricket.” Victorian History. Victorian Trading Co. August 24, 2014.