Mr. Hare: A Story for Children

By Anonymous [1]

Annotations by Rene Marzuk

Mr. Hare and Mr. Tortoise were, of course, great friends. Well, one nice warm day, when the sun was very hot in the thick African forest, they went out together a-hunting food, for they were very hungry. They walked and talked and talked and walked, when suddenly Mr. Tortoise stopped.

“Hello!” said Mr. Tortoise, pointing ahead.

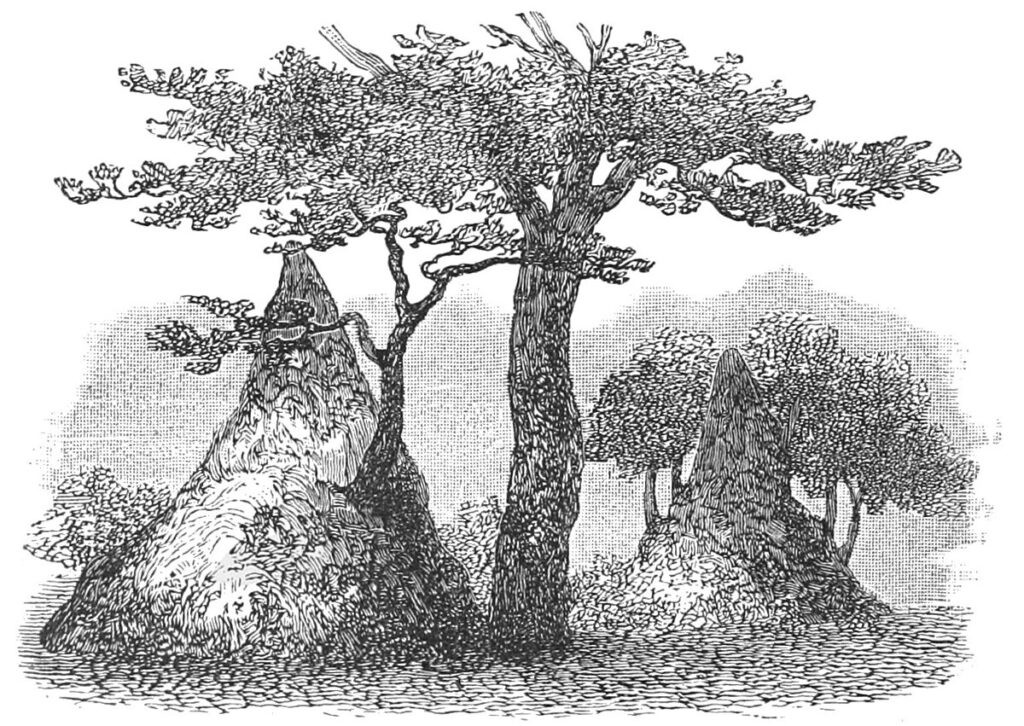

“Well, I never!”[2] answered Mr. Hare, beginning to scamper, for there right before them arose in the air, in one tall, slim column, a nice tall white-ant hill.[3]

Now everybody in Africa knows what sweet morsels fat white ants are, and you can believe that Mr. Hare and Mr. Tortoise were overjoyed at the sight of the hill and lost little time getting to it. Carefully they dug a nice little hole at the bottom of the hill and then sat down patiently to await the coming out of the ants.

As Mr. Hare waited he got so hungry that he began to reckon that after all there would be just about enough ants on that hill for Mr. Hare himself, and it seemed a shame to give up any of this fine food to a great sleepy tortoise.

So greedy Mr. Hare began to look about with one eye, keeping the other on the ant hill. Pretty soon Mr. Tortoise fell sound asleep just as Mr. Hare, pricking up his ears, heard some of his friends going through the forest. He ran quickly to them and asked them to carry the sleepy tortoise into the tall grass, where Mr. Hare knew it would he hard for him to crawl out.

“But be careful not to hurt him,” said Mr. Hare.

When the tortoise was out of the way, Mr. Hare sat down and ate and ate until he could hardly waffle, and then crept off home. Poor Mr. Tortoise, awaking in the tall thick grass, had a long hard journey to get out. When at last, late and exhausted, he arrived at the ant hill, lo! there was nothing left and Mr. Hare was gone.

“So ho! my fine friend,” said Mr. Tortoise, angrily.

“I’ll be even with you yet,” and he crawled off home.

Mr. Hare met him and made a great fuss.

“My dear old fellow!” he cried, “how glad I am to see you safe! I feared you were dead. I myself escaped by the merest chance. Three spears grazed me!” and Mr. Hare pointed to a very small scratch on his soft side.

‘”Humph,” said Mr. Tortoise, busily making his bed.

“We must not go to that ant hill again.” said Mr. Hare, licking his chops.

“Humph,” said Mr. Tortoise as he went to sleep.

Now Mr. Tortoise knew full well that early in the morning Mr. Hare would make a beeline to the ant hill for breakfast. Sure enough, up jumped Mr. Hare at dawn and slipped away. No sooner was he out of sight, however, than up jumped Mr. Tortoise and also crept quickly away to his friends.

“Wait for him.” he told them,” and when he has his head deep in the hole pounce on him.”

But Mr. Tortoise was kind hearted, and he remembered that Mr. Hare had been careful not to let his friends injure him when they carried him to the jungle. So he added:

“But don’t kill him.”

“Oh, but we like rabbit—we want to eat him!” cried the friends.

“Very well,” said Mr. Tortoise, “but if you kill him quickly he will be tough. You must take him home and make a big pot ready, half filled with fine oil and salt and nice herbs. Put Mr. Hare in it, but leave a hole in the cover so that you may add cold water from time to time. For if you let the oil get hot it will spoil the meat. So be very careful and not let it boil.”

The friends of the tortoise did exactly as they were told. Just as Mr. Hare was finishing the nicest breakfast imaginable, and stopping between mouthfuls to chuckle over the outwitting of the tortoise, he was suddenly seized from behind, and despite his frantic struggles hurried through the forest and dropped, splash! into a big pot of oil and herbs. Salt was added and the pot raised on sticks. Soon the crackling of a fire struck the scared ears of Mr. Hare, while Mr. Tortoise’s friends sat around in a circle and discussed the coming meal.

“I certainly do like rabbit,” said one.

“Do you think it as good as elephant steak?” asked another.

“Oh, better—much better,” said a third.

Here Mr. Hare, faint with fear and heat, was just about to give up, when, splash! and through a hole in the cover of the pot came a nice dash of cold water. Mr. Hare revived and looked about cautiously. This program was kept up for some hours, making poor Mr. Hare very nervous, indeed, until at last the patient cooks decided that their meal was ready; and indeed, the oil and herbs were giving off a most tempting smell.

All the feasters washed their hands, laid out the dishes, and, seating themselves in a circle, ran their tongues expectantly over their lips. The pot was placed in the middle and the cover removed, when, presto! out popped the very scared and bedraggled Mr. Hare and leaped into the jungle like a flash leaving a thin trail of oil.

“Dear me!” said Mr. Tortoise, as Mr. Hare rushed gasping into the house, “wherever have you been?”

“Whew!” cried Mr. Hare, “but I surely had a narrow escape. I was nearly murdered. I’ve been caught and cooked, and only by a miracle did I escape,” and he began hastily licking his oily sides.

Mr. Tortoise with difficulty kept back his laughter and watched Mr. Hare lick himself. Mr. Hare kept on licking and Mr. Tortoise crept nearer. Mr. Hare took no notice and Mr. Tortoise perceived that bit by bit the fright on Mr. Hare’s oily face was being replaced by the most emphatic signs of pleasure as Mr. Hare continued to lick himself greedily. Mr. Tortoise was interested, and stepping over quickly he began to lick the other side.

“My! how delicious,” he exclaimed in rapture, tasting the fine oil and salt and the flavor of the herbs.

“Get away!” cried the greedy Mr. Hare. ” You have not been in the pot and boiled. Keep off!”

Mr. Tortoise, feeling that he had had a hand in that oil and salt, began to get angry.

“Let me have your left shoulder to lick,” he demanded.

“I will not,” said Mr. Hare, who was now thoroughly enjoying himself. Mr. Tortoise stormed out of the house in a great fury and almost ran into the arms of his friends. They, too, were in a towering rage.

“What did you mean?” they cried. “Through your advice we’ve lost our hare and all our beautiful oil and salt.”

”Dear me!” exclaimed Mr. Tortoise, losing in his indignation all thoughts of friendship. “This is very, very sad. Now I will tell you what to do. Arrange a dance and invite Mr. Hare. When he is dancing to your tom-toms seize him and kill him.”

And this should have been the end of Mr. Hare. But it wasn’t.

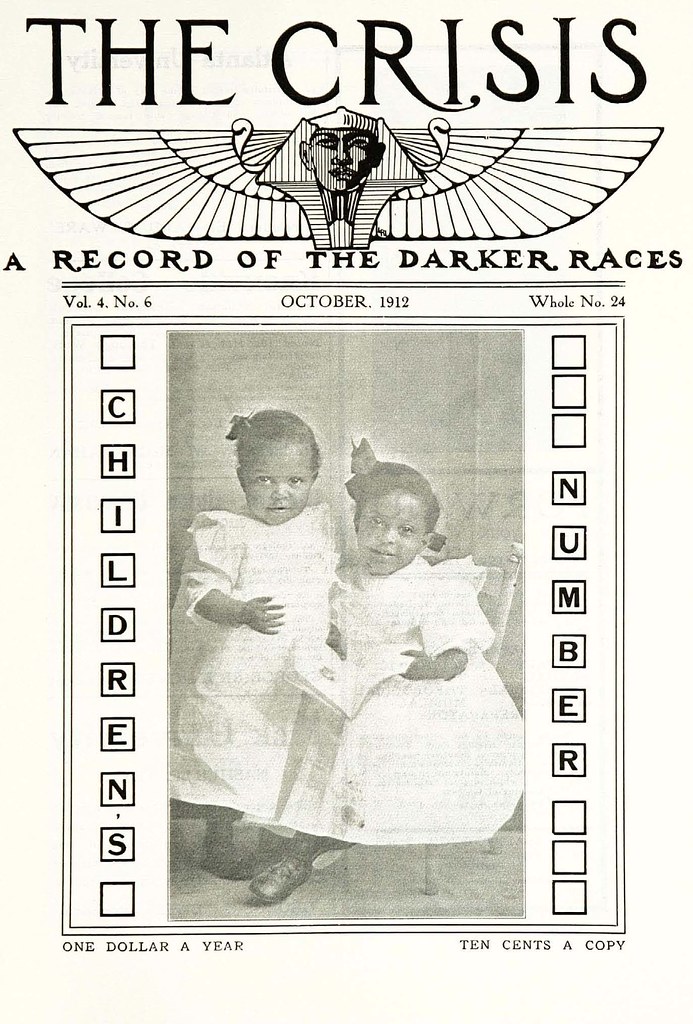

ANONYMOUS. “Mr. Hare: A Story for Children.” the crisis, Vol. 4, No. 6 (October 1912): 292-94

[1] “Mr. Hare: A Story for Children” appeared in the October, 1912 edition of The Crisis under the following byline: “Adapted from the folk tales of the Banyoro Negroes in Uganda, Central Africa, as reported by George Wilson in Sir Harry Johnston’s Uganda Protectorate.”

[2] British colloquial expression used to express surprise or indignation.

[2] White ants are not ants at all, but termites, social insects that build large nests and, due to the damage the cause to wooden structures, are widely classified as pests. Termites are actually edible. A good source of protein, fat and minerals, they probably figured in our ancestors’ diet. Many people eat them today.

Contexts

Starting in 1912, the October issues of The Crisis, the official magazine of the NAACP, were dedicated to children. A typical edition of these children’s numbers would contain a special editorial piece and two or three literary works specifically for children, while still including the serious pieces about contemporary issues with a focus on race that The Crisis was known for. These October numbers were sprinkled with children’s photographs sent in by the readers.

In his first editorial for the Children’s number in 1912, W. E. B. Du Bois wrote that “there is a sense in which all numbers and all words of a magazine of ideas myst point to the child—to that vast immortality and wide sweep and infinite possibility which the child represents.”

The success of The Crisis’ children’s number led to the standalone The Brownies’ Book, a monthly magazine for African American children that circulated from January 1920 to December 1921 under the editorship of Du Bois, Augustus Granville Dill, and Jessie Fauset.