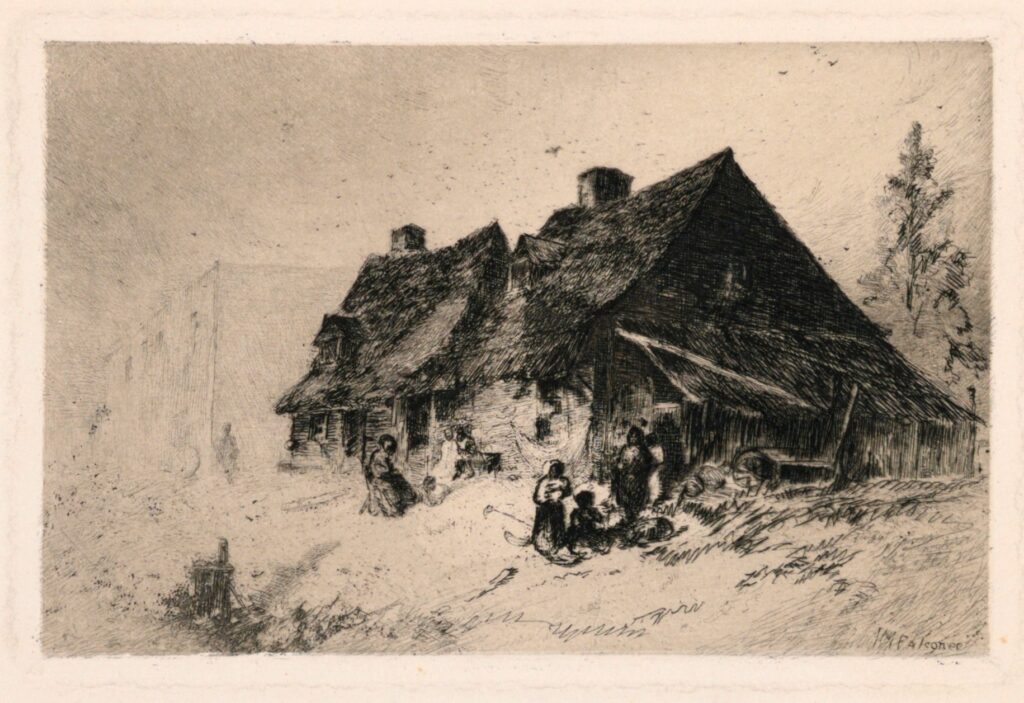

The Mountain Hut

By Rebecca Harding Davis

Annotations by josh benjamin

David, with his uncle and sister, had ridden far into the Balsam Mountains of North Carolina one day, leaving the bridle-path behind them and pushing their way through the underbrush of laurel and rowan, when a storm overtook them.

“There should be a hut on the bank of this stream,” said their uncle, “if my memory does not fail me.c

“I see it,” said David. “But it is more like a piggery than a dwelling for human beings, like most of the houses of these mountaineers.”

“These mountaineers are a kindly, honest folk, whatever their houses may be, and I am never afraid to claim a welcome, which I cannot always say of those who live in cities,” his uncle retorted.

The welcome in this case was given cordially. The hut was built of logs, between which were wide cracks; the rain beat in and ran down the floor.

“I like a plenty of air,” said their hostess, piling up logs on the hearth.

Her bed was a mattress of husks – it filled one corner, a rough pine table another; a heap of sacks full of roots lay piled near the door. The cooking utensils were a coffee-pot and two iron frying-pans. The woman stirred some corn-meal with water, filled one of the pans, put on the lid, and covered it with hot ashes; the other held a sizzling mess of fat pork.

“Yes, we’re very comfortable,” she said, proudly, observing Polly’s curious glances. “Got everything snug and genteel. I’d be powerful sorry to live like some folks.”

David followed his uncle out to the covered shed, where he sat looking at the pelting storm. “I never supposed any human beings lived in such solitude,” he exclaimed. “Why, she has not left the mountain for twenty years; she never has seen a town larger than the village of Waynesville—she did not know there was any larger.” [1]

“Still it is impossible for any living beings to shut themselves off from their kind. If you look a little farther, you will be surprised to find how widely connected this poor lame creature is with the rest of the world.”

“This coffee, which is making such a comfortable smell just now, came to her from the far-off Brazils; black-bearded mulattoes picked it for her on the shores of the Amazon; other slaves in the West Indies grew her the pepper which she is sifting on the meat; English mill-hands in Manchester wove her Sunday calico gown; mild-eyed Chinamen gave her tea; even this hen clucking at my feet came from eggs from Poland. [2]

“There is scarcely a State in the Union which has not its part in this poor little hut. Here is an axe; Pennsylvania gave the iron, Connecticut the handle. Here is sugar from Louisiana, rice from Georgia, shoes from Massachusetts.”

“The world is very liberal to the old woman,” said David, laughing. “She ought to give something in exchange.”

“Perhaps she does. We will look into that presently. I told you that we were all closely bound together. In a well-furnished city house there is scarcely a country in the world which is not represented, if you choose to search it out. You ask what the old woman sends back. Come, let us ask her. What is in this bag, for example?”

“Roots—Angelica,” promptly responded their hostess. “Pays eight cents in the pound, delivered in the village yonder. The doctors use it in the North to cure nervous people. That next bag – – – But set up, set up; dinner’s ready. Fall to, young folks; there’s plenty of it, sech as it is,” hospitably urging great chunks of hot Johnnycake on them and delicious yellow butter. David and Polly “fell to” with good will. [3]

“The other bag, you were about to say?” suggested their Uncle.

“Oh yes; ginseng. I gather heaps of that ‘ere. [4] My son takes it to the store, and it is shipped to New York, and from thar to China. Them poor heathen will pay its weight in gold for some kinds of ginseng. I don’t know what they do with it though.” [5]

“Going to China?” David said, looking respectfully at the sack.

“The Chinese believe that it gives fresh life to mind and body; cures all kinds of diseases. They mix it with dried caterpillars to give to insane people, and with powdered tigers’ skulls for the cure of grief.”

Polly laughed. “And what is in that smaller sack?” she asked.

“That is another root that goes with the ginseng to China. It has a pleasant smell, but I don’t know the name.”

“They burn it before their josses, to ensure themselves long live.”

“There is a queer gummy stuff in the bottle yonder. Does it go to China also?” asked Polly.

“No; that’s balsam. It’s the gum of these trees outside, with the black trunks. You’re nigh five thousand feet above the sea. They won’t grow no lower. They’re a mighty proud tree; and the chestnuts and oaks and sech like can’t grow so high, so you’ll notice on most of these mountings a barren strip between them whar thar’s nothing green.”

“But the bottle of gum? Is it used for mucilage?” asked David.

“No, no,” cried Polly, who had put the bottle to her nose. “I have smelled this often in cough-medicines and plasters and cures for burns.”

“What keen little eyes and nose you have, Polly,” said her brother, “for everything but books. Is she right, uncle?”

“Yes. Although the balsam commonly used in medicine comes from Russia. The supply from these mountains is very small. It sells high?” turning to the woman.

“Ten dollars a quart here, and more ef you kerry it to town. Oh, thar’s a fortune in balsam! [6] Bar-skins is worth a powerful sight of money, wolf-skins not quite so much. My baby (I call him my baby, though he’s twenty-one, bein’ the youngest), he took down some peltry yesterday. Bar, wolf, deer, coon and boomer. They do tell me ladies up North have them bigger skins to cover their coachmen’s feet; but I don’t believe it. They’ve surely got wit to know what fine bedspreads they make.” [7]

The children by this time had finished their dinner. “Here are some strange-looking yellow stones,” said Polly, with an inquiring glance.

“Oh, them rocks? You see a man was around hyar prospectin’ for mines, and he left word with my boy to look out for sech rocks as that, and mark the place. Expects to find gold, I reckon?”

“Something more valuable than gold. This is yellow corundum.”

“What is it used for?”

“This coarse kind is ground to make emery, which Polly sharpens her needles with. The finer corundums are the sapphire and the oriental ruby.” [8]

“Oh!” cried Polly, breathlessly. “Do you mean that rubies are to be found here—here?”

“One was found in the next county worth six thousand dollars,” said the mountaineer. “I suppose the folks that live in towns couldn’t get along very well without us North Carlinyans,” smiling. “We send ‘em lumber and iron and gold and medicine, and even rings for their fingers.”

The rain had eased, and they bade her a cordial good-by, and rode away.

“Instead of being in a solitude, she is quite in the centre of things,” said David, laughing.

“I told you that we were all tied together by fine cords,” said his uncle; “you are just beginning to find out how many of them there are.”

DAVIS, REBECCA HARDING. “THE MOUNTAIN HUT.” THE YOUTH’S COMPANION 58, NO. 27 (JULY 1885): 271.

[1] According to 1890 census data, Waynesville township (a larger area that included the towns of Hazelwood and Waynesville) in Haywood County had a population of 2,506; Waynesville town alone had 455 residents. [10]

[2] The last enslaved people in Brazil were freed on May 13, 1888. British slavery in the Caribbean was slowly ended between 1807 and 1838, French slavery was abolished in 1848, and the Dutch ended it in 1863. Spanish slavery continued in Puerto Rico until 1873 and in Cuba until 1886.

[3] Angelica, also known as wild celery, is in the carrot family and has roots, seeds, leaves, and fruit used for medicine. Johnnycake is a cornmeal flatbread.

[4] Ginseng was a lucrative southern Appalachian crop, particularly from 1860 through the 1880s. The U.S. exported over 6 million pounds in the 1880s. The people who gathered ginseng to sell were called “sang diggers” or “sangers.” [11]

[5] In the 1800s, discrimination against Chinese people was widespread in the U.S., and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was the first major law to restrict immigration.

[6] Balsam resin is similar to sap. In Western N.C., it was often collected from Fraser firs (often called “balsams”) by poking the blisters it forms on the bark. [12] Ten dollars in 1885 would be almost $270 in 2020.

[7] Black bears (“bar”) are common in North Carolina’s Blue Ridge Mountains, as were the now-rare red and gray wolves. State records show the last gray wolf was taken from Haywood County in 1887. “Boomer” was a local term for the red squirrel.

[8] Corundum can be any color, although rubies and sapphires are common. Only diamond and moissanite are harder minerals.

Contexts

Rebecca Harding Davis was a famous, important nineteenth-century American writer for adults, perhaps best known for her short story “Life in the Iron Mills,” which brought the conditions of life for industrial workers to a large audience. She wrote several “local color sketches” in the late 1870s and 1880s, often using the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina as a setting. Davis had seen the mountaineers firsthand and frequently used their existence in remote nature as a contrast with outside visitors, often from northern states. [9]

Definitions from Oxford English Dictionary:

joss: A Chinese figure of a deity, an idol.

mucilage: An adhesive consisting of an aqueous solution; gum, glue. A viscid preparation made from the seeds, roots, or other parts of certain plants by soaking or heating them in water, used medicinally in soothing poultices, tisanes, etc.

Resources for Further Study

- The collected works of Rebecca Harding Davis.

- A brief look at Davis as an early American realist.

- Rebecca Harding Davis: A Life Among Writers by Sharon Harris is an excellent, comprehensive view of Davis’s life and career.

[9] Rose, Jane Atteridge. “Homebound (1875-1889).” In Rebecca Harding Davis, 103-131. Twayne’s United States Authors Series 623. New York, NY: Twayne, 1993. Gale eBooks. Accessed September 21, 2020. https://link-gale-com.libproxy.uncg.edu/apps/doc/CX2322800015/GVRL?u=gree35277&sid=GVRL&xid=f2e89f8f.

[10] https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1910/abstract/supplement-nc.pdf

[11] Manget, Luke. “Sangin’ Io the Mountains: The Ginseng Economy of the Southern Appalachians, 1865-1900.” Appalachian Journal 40, no. 1/2 (2012): 28-56. Accessed September 27, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43489051.

[12] Sidebottom, Jill. “Chapter 2 – Why Fraser Fir?,” 2014. Accessed September 27, 2020. https://christmastrees.ces.ncsu.edu/christmastrees-chapter-2-why-fraser-fir/.