A Legend of the Blue Jay

By Ruth Anna Fisher

Annotations by Rene Marzuk

It was a hot, sultry day in May and the children in the little school in Virginia were wearily waiting for the gong to free them from lessons for the day. Furtive glances were directed towards the clock. The call of the birds and fields was becoming more and more insistent. Would the hour never strike!

“The Planting of the Apple-tree” had no interest for them. Little attention was given the boy as he read in a sing-song, spiritless manner:

"What plant we in this apple-tree? Buds, which the breath of summer days Shall lengthen into leafy sprays; Boughs where the thrush, with crimson breast, Shall haunt and sing and hide her nest."[1]

The teacher, who had long since stopped trying to make the lesson interesting, found herself saying mechanically, “What other birds have their nests in the apple-tree?”

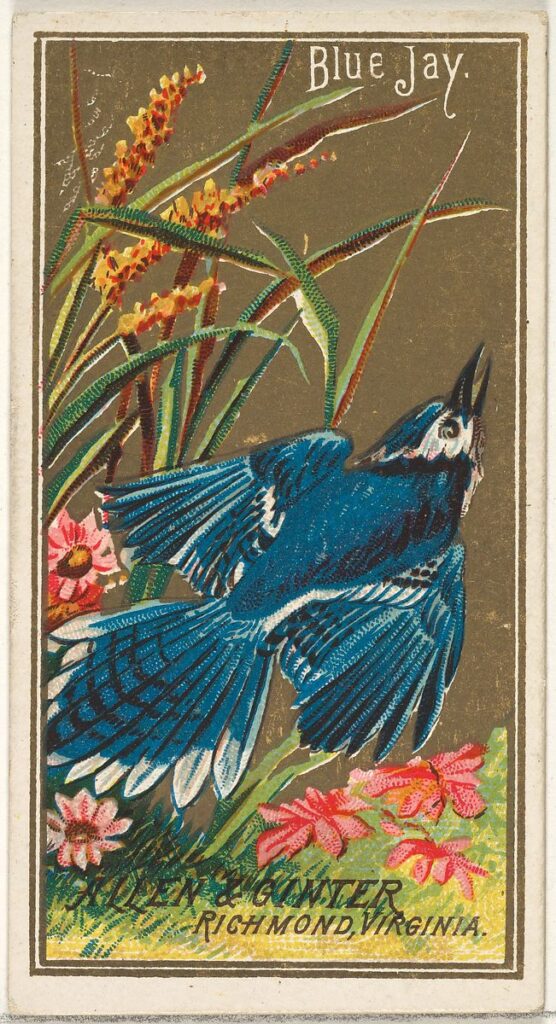

The boy shifted lazily from one foot to the other as he began, “The sparrow, the robin, and wrens, and—the snow-birds and blue-jays—”

“No, they don’t, blue-jays don’t have nests,” came the excited outburst from some of the children, much to the surprise of the teacher.[2]

When order was restored some of these brown-skinned children, who came from the heart of the Virginian mountains, told this legend of the blue-jay.

Long, long years ago, the devil came to buy the blue-jay’s soul, for which he first offered a beautiful golden ear of corn. This the blue-jay liked and wanted badly, but said, “No, I cannot take it in exchange for my soul.” Then the devil came again, this time with a bright red ear of corn which was even more lovely than the golden one.

This, too, the blue-jay refused. At last the devil came to offer him a wonderful blue ear. This one the blue-jay liked best of all, but still was unwilling to part with his soul. Then the devil hung it up in the nest, and the blue-jay found that it exactly matched his own brilliant feathers, and knew at once that he must have it. The bargain was quickly made. And now in payment for that one blue ear of corn each Friday the blue-jay must carry one grain of sand to the devil, and sometimes he gets back on Sunday, but oftener not until Monday.[3]

Very seriously the children added, “And all the bad people are going to burn until the blue-jays have carried all the grains of sand in the ocean to the devil.”

The teacher must have smiled a little at the legend, for the children cried out again, “It is so. ’Deed it is, for doesn’t the black spot on the blue-jay come because he gets his wings scorched, and he doesn’t have a nest like other birds.”

Then, to dispel any further doubts the teacher might have, they asked triumphantly, “You never saw a blue-jay on Friday, did you?”

There was no need to answer, for just then the gong sounded and the children trooped happily out to play.

Fisher, Ruth Anna. “A Legend of the Blue Jay,” IN THE UPWARD PATH: A READER FOR COLORED CHILDREN, ED. MYRON T. PRITCHARD AND MARY WHITE OVINGTON, 218-19. HARCOURT, BRACE AND HOWE, 1920.

[1] American nature poet and journalist William Cullen Bryant (1794-1878) wrote “The Planting of the Apple-Tree,” a poem included in school readers like The Rand-McNally List of Selections in School Readers (1896) and Constructive English for the Higher Grades of the Grammar School (1915).

[2] Blue jays do build nests. However, according to the Audubon Society‘s website, they are very quiet and inconspicuous when around them.

[3] According to folktales and fables that circulated within enslaved communities in the antebellum American South, the blue jay was never seen on Fridays because on those days he was carrying sticks to the devil to pay his debt. In other stories, the bird acted as the devil’s helper or messenger. Some of these accounts appear in Ernest Ingersoll’s Birds in Legend, Fable and Folklore (1923), Martha Young’s Plantation Legends (1902), and others.

Contexts

This short story was included in The Upward Path: A Reader for Colored Children, published in 1920 and compiled by Myron T. Pritchard and Mary White Ovington. The volume’s foreword states that, “[t]o the present time, there has been no collection of stories and poems by Negro writers, which colored children could read with interest and pleasure and in which they could find a mirror of the traditions and aspirations of their race.”

Definitions from Oxford English Dictionary:

- sing-song: To utter or express in a monotonous chant.

Resources for Further Study

- Brief essay posted in The Conversation about the role of African American folklore in the preservation of history and cultural memory.

- An overview of education in Virginia from 1869 to the present helps contextualize the school where Fisher’s story takes place. For example, under the Jim Crow system of education, “[o]ften transportation was provided to white schools but not to black ones. White teachers earned more money than black teachers, and male teachers were paid more than female teachers.”

- A defense of the blue jay, a bird that “birders love to hate.”

Contemporary Connections

Blue jays are protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, passed by the U.S. Congress in 1918.