Animal Life in the Congo

By William Henry Sheppard

Annotations by Rene Marzuk

At daybreak Monday morning we had finished our breakfast by candle light and with staff in hand we marched northeast for Lukunga. [1]

In two days we sighted the Mission Compound. Word had reached the missionaries (A. B. M. U.) that foreigners were approaching, and they came out to meet and greet us. [2] We were soon hurried into their cool and comfortable mud houses. Our faithful cook was dismissed, for we were to take our meals with the missionaries.

Mr. Hoste, who is at the head of this station, came into our room and mentioned that the numerous spiders, half the size of your hand, on the walls were harmless. “But,” said he, as he raised his hand and pointed to a hole over the door, “there is a nest of scorpions; you must be careful in moving in or out, for they will spring upon you.”

Well, you ought to have seen us dodging in and out that door. After supper, not discrediting the veracity of the gentleman, we set to work, and for an hour we spoiled the walls by smashing spiders with slippers.

The next morning the mission station was excited over the loss of their only donkey. The donkey had been feeding in the field and a boa-constrictor had captured him, squeezed him into pulp, dragged him a hundred yards down to the river bank, and was preparing to swallow him.[3] The missionaries, all with guns, took aim and fired, killing the twenty-five-foot boa-constrictor. The boa was turned over to the natives and they had a great feast. The missionaries told us many tales about how the boa-constrictor would come by night and steal away their goats, hogs, and dogs.

The sand around Lukunga is a hot-bed for miniature fleas, or “jiggers.” [4] The second day of our stay at Lukunga our feet had swollen and itched terribly, and on examination we found that these “jiggers” had entered under our toe nails and had grown to the size of a pea. A native was called and with a small sharpened stick they were cut out. We saw natives with toes and fingers eaten entirely off by these pests. Mr. Hoste told us to keep our toes well greased with palm oil. We followed his instructions, but grease with sand and sun made our socks rather “heavy.”

The native church here is very strong spiritually.

The church bell, a real big brass bell, begins to ring at 8 A. M. and continues for an hour. The natives in the neighborhood come teeming by every trail, take their seats quietly, and listen attentively to the preaching of God’s word. No excitement, no shouting, but an intelligent interest shown by looking and listening from start to finish.

In the evening you can hear from every quarter our hymns sung by the natives in their own language. They are having their family devotions before retiring.

Our second day’s march brought us to a large river. Our loads and men were ferried over in canoes. Mr. Lapsley and I decided to swim it, and so we jumped in and struck out for the opposite shore. On landing we were told by a native watchman that we had done a very daring thing. He explained with much excitement and many gestures that the river was filled with crocodiles, and that he did not expect to see us land alive on his side. We camped on the top of the hill overlooking N’Kissy and the wild rushing Congo Rapids. It was in one of these whirlpools that young Pocock, Stanley’s last survivor, perished.

In the “Pool” we saw many hippopotami, and longed to go out in a canoe and shoot one, but being warned of the danger from the hippopotami and also of the treacherous current of the Congo River, which might take us over the rapids and to death, we were afraid to venture. A native Bateke fisherman,[5] just a few days before our arrival, had been crushed in his canoe by a bull-hippopotamus.[6] Many stories of hippopotami horrors were told us.

One day Chief N’Galiama with his attendant came to the mission and told Dr. Simms that the people in the village were very hungry and to see if it were possible for him to get some meat to eat.

Dr. Simms called me and explained how the people were on the verge of a famine and if I could kill them a hippopotamus it would help greatly. He continued to explain that the meat and hide would be dried by the people and, using but a little at each meal, would last them a long time. Dr. Simms mentioned that he had never hunted, but he knew where the game was. He said, “I will give you a native guide, you go with him around the first cataract about two miles from here and you will find the hippopotami.” I was delighted at the idea, and being anxious to use my “Martini Henry” rifle and to help the hungry people, I consented to go.[7] In an hour and a half we had walked around the rapids, across the big boulders, and right before us were at least a dozen big hippopotami. Some were frightened, ducked their heads and made off; others showed signs of fight and defiance.

At about fifty yards distant I raised my rife and let fly at one of the exposed heads. My guide told me that the hippopotamus was shot and killed. In a few minutes another head appeared above the surface of the water and again taking aim I fired with the same result. The guide, who was a subject of the Chief N’Galiama, sprang upon a big boulder and cried to me to look at the big bubbles which were appearing on the water; then explained in detail that the hippopotami had drowned and would rise to the top of the water within an hour.

The guide asked to go to a fishing camp nearby and call some men to secure the hippopotami when they rose, or else they would go out with the current and over the rapids. In a very short time about fifty men, bringing native rope with them, were on the scene and truly, as the guide had said, up came the first hippopotamus, his big back showing first. A number of the men were off swimming with the long rope which was tied to the hippopotamus’ foot. A signal was given and every man did his best. No sooner had we secured the one near shore than there was a wild shout to untie and hasten for the other. These two were securely tied by their feet and big boulders were rolled on the rope to keep them from drifting out into the current.

The short tails of both of them were cut off and we started home. We reported to Dr. Simms that we had about four or five tons of meat down on the river bank. The native town ran wild with delight. Many natives came to examine my gun which had sent the big bullets crashing through the brain of the hippopotami. Early the next morning N’Galiama sent his son Nzelie with a long caravan of men to complete the work. They leaped upon the backs of the hippopotami, wrestled with each other for a while, and then with knives and axes fell to work. The missionaries enjoyed a hippopotamus steak that day also.

Before the chickens began to crow for dawn I was alarmed by a band of big, broad-headed, determined driver ants.[8] They filled the cabin, the bed, the yard. There were millions. They were in my head, my eyes, my nose, and pulling at my toes. When I found it was not a dream, I didn’t tarry long.

Some of our native boys came with torches of fire to my rescue. They are the largest and the most ferocious ant we know anything about. In an incredibly short space of time they can kill any goat, chicken, duck, hog or dog on the place. In a few hours there is not a rat, mouse, snake, centipede, spider, or scorpion in your house, as they are chased, killed and carried away. We built a fire and slept inside of the circle until day.

We scraped the acquaintance of these soldier ants by being severely bitten and stung. They are near the size of a wasp and use both ends with splendid effect. They live deep down in the ground and come out of a smoothly cut hole, following each other single file, and when they reach a damp spot in the forest and hear the white ants cutting away on the fallen leaves, the leader stops until all the soldiers have caught up. A circle is formed, a peculiar hissing is the order to raid, and down under the leaves they dart, and in a few minutes they come out with their pinchers filled with white ants. The line, without the least excitement, is again formed and they march back home stepping high with their prey.

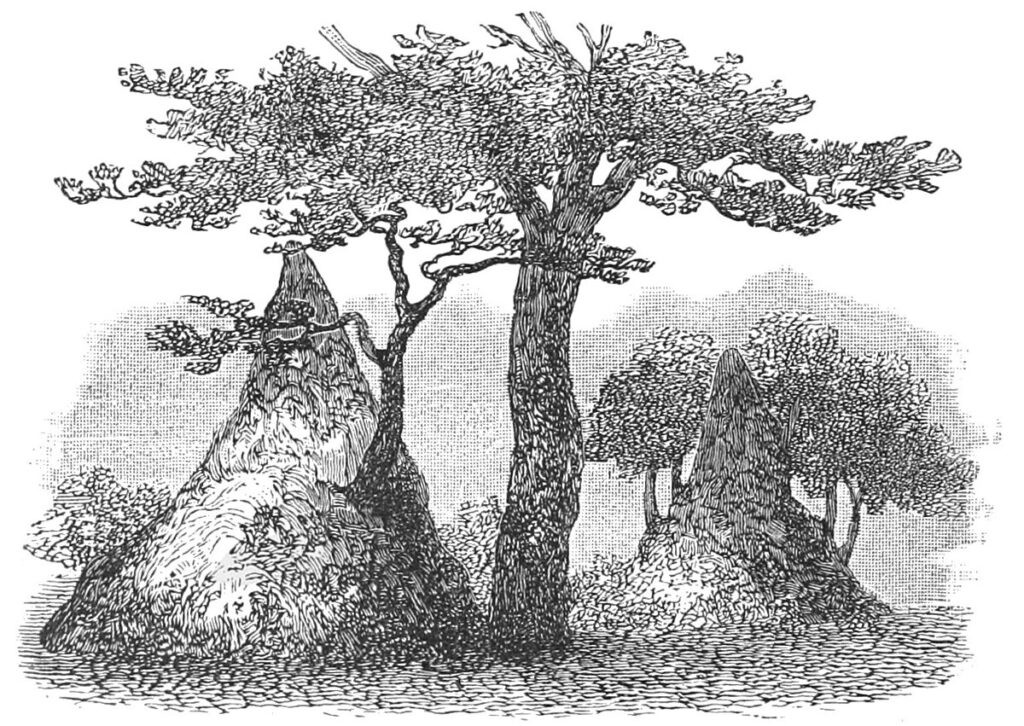

The small White Ants have a blue head and a white, soft body and are everywhere in the ground and on the surface. They live by eating dead wood and leaves.[9]

We got rid of the driver ants by keeping up a big fire in their cave for a week. We dug up the homes of the big black ants and they moved off. But there was no way possible to rid the place of the billions of white ants. They ate our dry goods boxes, our books, our trunks, our beds, shoes, hats and clothing. The natives make holes in the ground, entrapping the ants, and use them for food.[10]

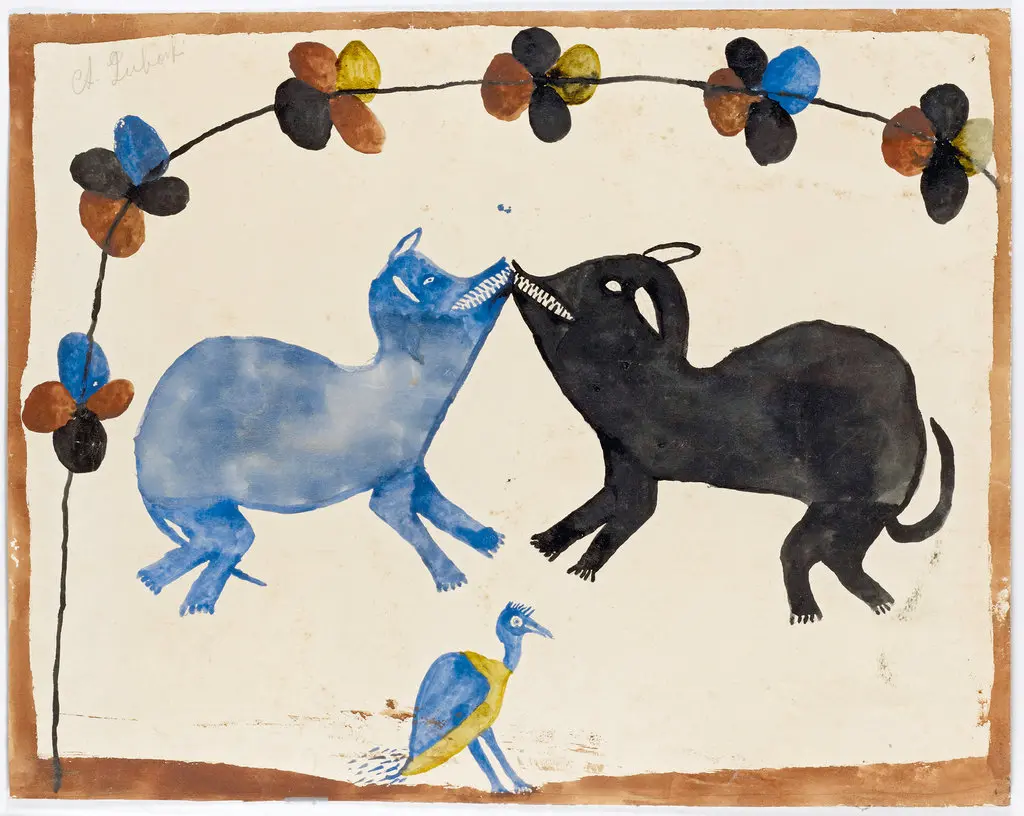

The dogs look like ordinary curs, with but little hair on them, and they never bark or bite. I asked the people to explain why their dogs didn’t bark. So they told me that once they did bark, but long ago the dogs and leopards had a big fight, the dogs whipped the leopards, and after that the leopards were very mad, so the mothers of the little dogs told them not to bark any more, and they hadn’t barked since.[11]

The natives tie wooden bells around their dogs to know where they are. Every man knows the sound of his bell just as we would know the bark of our dog.

There are many, many kinds of birds of the air, all known and called by name, and the food they eat, their mode of building nests, etc., were familiar to the people. They knew the customs and habits of the elephant, hippopotamus, buffalo, leopard, hyena, jackal, wildcat, monkey, mouse, and every animal which roams the great forest and plain, – from the thirty-foot boa-constrictor to a tiny tulu their names and nature were well known.

The little children could tell you the native names of all insects, such as caterpillars, crickets, cockroaches, grasshoppers, locusts, mantis, honey bees, bumble bees, wasps, hornets, yellow jackets, goliath beetles, stage beetles, ants, etc.

The many species of fish, eels and terrapins were on the end of their tongues, and these were all gathered and used for food. All the trees of the forest and plain, the flowers, fruits, nuts and berries were known and named. Roots which are good for all maladies were not only known to the medicine man, but the common people knew them also.

SHEPPARD, WILLIAM HENRY. “ANIMAL LIFE IN THE CONGO,” IN THE UPWARD PATH: A READER FOR COLORED CHILDREN, ED. MYRON T. PRITCHARD AND MARY WHITE OVINGTON, 135-42. NEW YORK: HARCOURT, BRACE AND HOWE, 1920.

[1] Lukunga is a district of Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo’s capital.

[2] ABMU is the acronym for the American Baptist Missionary Union, an international missionary society founded in 1814.

[3] Boa constrictors are endemic to the Americas, not Africa. The biggest snake in Africa is the African Rock Python, which can reach a length of 20 to 30 feet.

[4] The chigoe flea, commonly known as jigger, causes a painful infestation that included borrowing under the host’s skin. Originally from the South America and the Caribbean, jiggers spread to Africa at the end of the 19th century.

[5] The Teke or Bateke people are a Bantu Central African ethnic group mainly located in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The word “teke” means “to buy.”

[6] Male hippopotami are called bulls and female hippopotami are called cows. They are very territorial.

[7] The British Empire adopted the Martini-Henry rifle in 1871 and kept it in service for 47 years. This firearm is sometimes referred to as a weapon of Empire.

[8] Driver ants, which belong to the genus Dorylus, hunt together for prey in massive swarm raids. Due to their ferocity, they effectively “drive” many animals before them.

[9] White ants are not ants at all, but termites, social insects that build large nests and, due to the damage the cause to wooden structures, are widely classified as pests.

[10] Yes, termites are edible! A good source of protein, fat and minerals, they probably figured in our ancestors’ diet and many people eat them today.

[11] The Basenji is a very old breed of dog hound native to central Africa. Although known as “the barkless dog,” they do produce yodel-like vocalizations.

Contexts

Sheppard’s essay was included in The Upward Path: A Reader for Colored Children, published in 1920 and compiled by Myron T. Pritchard and Mary White Ovington. The volume’s foreword states that, “to the present time, there has been no collection of stories and poems by Negro writers, which colored children could read with interest and pleasure and in which they could find a mirror of the traditions and aspirations of their race.”

Definitions from Oxford English Dictionary:

cur: A dog: now always depreciative or contemptuous; a worthless, low-bred, or snappish dog. Formerly (and still sometimes dialectally) applied without depreciation, especially to a watchdog or shepherd’s dog.

Resources for Further Study

- Photographs of driver ants.

- “Basenji History: Behind the “Barkless” Dog of the Congo.”

- Visit the collection of William Henry Sheppard’s papers a the Presbyterian Historical Society’s website.

- Texts written by and about Sheppard at the Log College Press’s website, which collects writings from American presbyterians from the 18th and 19th centuries.

Contemporary Connections

A CNN article on the impact of chigoe fleas (jiggers) in sub-Saharan Africa: “The parasite keeping millions in poverty.”