Black Cat Magic

By Edna M. Harrold

Annotations by Kathryn t. burt

I’m sick and tired of hearing about it, that’s what,” said Carl Gray wearily. “Every time I pick up a newspaper or magazine there’s a whole lot in it about psychical research.[1] Talk about something else.”

“Well you’re foolish and behind the times, that’s all I’ve got to say,” retorted Ray Fulton, hotly. The leading men of the world are taken up with it, and it’s a good thing to know about.

“Why is it a good thing to know about?” sneered Carl.

“Well because it is, that’s why. And if you don’t buy a ticket from me you’re a cheap skate and not my buddy. Work all the week after school at the drug store and then won’t even buy a twenty-five cent ticket!”

Carl assumed an air of indifference he was far from feeling.

“I don’t care how much I work, or what kind of a skate I am; I’m not going to buy any ticket to any lecture.[2] See?”

And without further parley he walked off, complacently jingling his week’s wages in his pocket. Four of these silver dollars were to swell the fund he was saving to pay his expenses at the State University two years hence. The remaining dollar was his spending money for the week. And when one has only a dollar to spend, it behooves one to be as saving as possible, especially when one has a healthy appetite for caramel sodas.

If it had been a lecture on foreign travel now, Carl would not have minded buying a ticket. Of course Ray was his chum, his sworn and chosen buddy and he’d help him in any way he could. But it wasn’t Carl’s fault that Ray had been such a boob as to let some old professor foist a lot of tickets off on him with the promise of a dollar if he sold them all. Let Ray earn his spending money by the honest sweat of his brow as became any sober-minded high school sophomore.

The next morning on his way to school he met Ray again and girded himself for a renewal of hostilities.

“Well, Arbaces,”[3] he said insolently (his class was reading the ‘Last Days of Pompeii’), “how many tickets have you sold now?” As he spoke he tossed his silver dollar high in the air.

“That’s all right about my tickets,” returned Ray with a forced laugh. He saw that Carl had money and was to be treated civilly, at least until he had treated him to one or two sodas. “You know, Carl, I’m just seeing how many tickets I can sell for the money that’s in it. I don’t believe in that rot any more than you do.”

Here both boys turned as one and walked backward nine steps. A black cat had crossed their path. They turned around again, spat, and then looked at each other sheepishly.

“There’s nothing in it that it’s bad luck to have a black cat cross your path,” said Carl the materialist, “I just walked backward because you did.” [4]

“Yes you did not,” jeered Ray. “But I’ll tell you what’s a true fact: If you boil a black cat alive and then chew a certain bone that comes out of its head you’ll be able to do anything in this world that you want to, no matter what it is.” [5]

Carl shouted aloud in derision, “It’s a wonder you wouldn’t chew ten black cat bones then so you could get your geometry lessons,” he shouted. (Carl was the fifteen year old head of his mathematics class.)

“Laugh if you want to but it’s true,” said Ray sullenly. He really didn’t half believe it himself, but he wasn’t going to admit that Carl Gray knew everything.

“Rats,” said Carl. “If that was the truth, there wouldn’t be a black cat left in this town. Everybody would be boiling them alive and eating their bones.”

“It’s not their bones, smarty. It’s just one bone. And everybody don’t know that certain bone, and that’s why everybody can’t do the trick.”

“Well, do you know what certain bone it is?”

“Sure I do.”

“What bone is it, then?”

“It’s a bone in the cat’s head I told you.”

“Yes I know you told me it was a bone in the cat’s head. But a cat’s got more than one bone in its head, and you said it was a certain one. Now which one is it?”

“Well, after school we’ll get a black cat.”

“Where’ll we get one? Besides, it has to be boiled alive. You get me a black cat and boil it alive, and I’ll show you the bone all right.”

“If you want any black cat boiled alive you’ll boil it yourself. It’s bad luck to kill a cat.”

“Well, I can’t show you if I don’t have a cat, that’s all there is to it.”

Conversation languished until the boys reached school. Carl was plunged into thought. He told himself that he didn’t believe in Ray’s silly trick for a moment; he was just betting that the bone couldn’t be found that was all.

That evening when he had finished his work at the drug store he sought Ray’s house. “I say, Ray,” he began, “if we could find a black cat that was dead already couldn’t you boil it and show me that bone?”

“Well, I guess maybe I could. Of course it wouldn’t do you any good to chew the bone of a dead cat but I could show it to you.”

“All right. Tomorrow’s Saturday and I’ll be off at three o’clock. You meet me at the drugstore and we’ll find a cat.”

But next day their search was unavailing, although they looked through alleys and creeks and even went to the edge of the river where the city dumping grounds were. They were just about to give it up when they met the city scavenger, driving his team of fat horses.

“Hey, Mr. Miller, let us look in your wagon, will you? Let us look and see if you’ve got a black cat there,” called Carl, seized with a bright idea. Mr. Miller, always on the alert against just such boyish pranks as this, scanned the pair with a fishy eye and rode off without replying.

“Well, I don’t care,” said Ray with an air of relief, “Let’s go on home, I’m hungry.”

So the boys moved off at a run, and taking a short cut towards home were quite unexpectedly rewarded, for, in an old unused pasture, among tin cans, old buckets and other débris they came upon a defunct feline, black as ebony and swollen to the proportions of a small dog.

With an exultant whoop the boys seized their prize and hurried on. “Now I’ll have to go back to work. But I’ll take this cat and hide it in my woodshed and Monday non when we come home to dinner we’ll boil her then. Mother’ll be away all day and we’ll have the house to ourselves. Say, you carry it a while. It doesn’t smell exactly like cologne, does it?”

It did not and both boys were glad when they had deposited their noisome burden in Carl’s woodshed. By Monday noon Carl’s interest in psychical research had diminished considerably. He had passed a very uncomfortable Sabbath trying to keep his parents from finding out just what caused that peculiarly offensive odor about the premises. But now Ray was on hand and so was the dead cat, so there was nothing to do but go on with the experiment.

Carl lighted the gasoline stove and filled the clothes boiler with water. “We’ll boil it in that and while it’s boiling we’ll eat our dinner,” he told Ray.

Ray nodded and put the cat into the boiler trying not to mind the horrible odor. Then the boys washed their hands and Carl started to place lunch on the table. But the aroma from the boiler became more and more pronounced and Carl began to have serious doubts as to the wisdom of the step they had taken. Visions of an irate mother passed through his mind and he wondered if he would ever be able to get that awful scent out of the clothes boiler.

He looked at Ray. Ray looked sick and said he didn’t believe he wanted any lunch. Carl did not urge him; his own appetite had vanished. For a few terrible minutes they sat still and then the boiler boiled over.

That was the end.

“For the love of the queen,” shuddered Carl, “Help me throw that rotten thing out of here.”

Choking, gasping, and staggering the boys carried the boiler far down the alley and emptied it.

“Shall—shall I show you that bone now?” quavered Ray, forcin ghimself to gaze on the repulsive mass at their feet.

Carl turned savagely. “You shut up that foolishness, right now,” he snapped. “I’ve made a big enough boob of myself hiding a dead cat, let alone messing through it looking for a bone. Don’t you ever come to me with that tale again. D’you hear?”

And he marched off, leaving Ray standing in the alley, a dejected and misunderstood disciple of black cat magic.

Harrold, edna m. “black cat magic.” The Brownies’ Book 2, no. 5 (May 1921): 131-33.

[1] The effort to use scientific procedures and principles to explain psychic experiences, including hypnotism, séances, hauntings, and telepathy (Sommer).

[2] In the early 1900s, professors commonly sold tickets to their scientific lectures, surgeries, or dissection demonstrations (Kirschke and Sintiere 163-64).

[3] The Last Days of Pompeii is a novel by Edward Bulwer-Lytton about the lives of Romans in the city of Pompeii before the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD. Arbaces, the character to which Carl compares Ray, is the villainous sorcerer who murders the heroine’s brother.

[4] Superstitions surrounding black cats are inconsistent. While black cats are associated with witches in England and the United States, some places hold that the appearance of a black cat is lucky. For example, in Yorkshire (England), fishermen kept black cats as pets to ensure the safety of sailors (Radford and Radford).

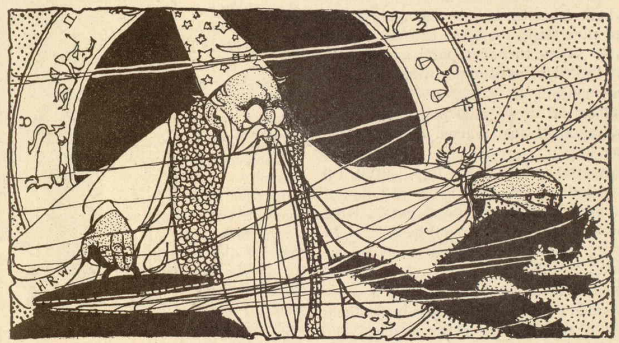

[5] According to Zora Neale Hurston, an American anthropologist and novelist, the black cat bone ritual Carl and Ray attempt will make the spell-caster invisible. Successful completion of the ritual involves fasting for twenty-four hours, catching and boiling a black cat alive, cursing the cat as it dies, and testing the cat’s bones until one tastes bitter.

Contexts

The American Society for Psychical Research (ASPR) was founded in 1885 after the British physicist and parapsychologist Sir William Fletcher Barrett visited the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 1884 (Fichman). Among the society’s founding members were Edward Charles Pickering, Alpheus Hyatt, Henry Pickering Bowditch, and William James. The first president, Simon Newcomb, was a skeptic who “hoped to convince others that, on methodological grounds, psychical research was a scientific dead end” (Moyer 92). However, others in the society had more belief in the possible veracity of phenomena like telepathy and psychological automatisms. The ASPR struggled to maintain funding and interest, and membership fluctuated throughout the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In 1920, after the death of psychologist and ASPR secretary James Hyslop, the society splintered due to differences in belief (Mauskopf).

Resources for Further Study

- Fichman, Martin. An Elusive Victorian: The Evolution of Alfred Russel Wallace. University of Chicago Press, 2004.

- Foreman, Amanda. “The Dark Lore of Black Cats.” Wall Street Journal, 18 October 2018.

- Hurston, Zora Neale. Mules and Men. Harper Perennial, 1990.

- Kirschke, Amy Helene and Phillip Luke Sintiere, eds. Protest and Propaganda : W. E. B. Du Bois, the CRISIS, and American History. University of Missouri Press, 2019.

- Mauskopf, Seymour. “Psychical Research in America.” Psychical Research: A Guide to Its History, Principles & Practices, ed. Ivor Grattan-Guinness. Aquarian Press, 1982.

- Moyer, Albert E. 1998. “Simon Newcomb: Astronomer with an Attitude.” Scientific American 279, no. 4 (1998): 88-93.

- Musser, Judith, ed. “Girl, Colored” and Other Stories: A Complete Short Fiction Anthology of African American Women Writers in The Crisis Magazine, 1910-2010. McFarland, 2010.

- Radford Edwin, and Mona A. Radford. Encyclopedia of Superstitions. Philosophical Library, 2007.

- Sommer, Andreas. “Psychical research in the history and philosophy of science. An introduction and review.“ Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences, 48 (2020): 38-45.

Contemporary Connections

There are several good modern books for children about superstitions:

- History’s Witches: An Illustrated Guide by Lisa Graves

- Invincible Magic Book of Spells: Ancient Spells, Charms and Divination Rituals for Kids in Magic Training by Catherine Fet

- Juju the Good Voodoo by Michelle Hirstius

- Knock On Wood: Poems About Superstitions by Janet S. Wong and Julie Paschkis

- Superstition: Black Cats and White Rabbits—The History of Common Folk Beliefs by Sally Coulthard

- Superstitions: A Handbook of Folklore, Myths, and Legends from Around the World by D. R. McElroy

- The Illustrated History of Magic by Milbourne and Maurine Christopher

- The Junior Witch’s Handbook: A Kid’s Guide to White Magic, Spells, and Rituals by Nikki van de Car

- Witches, Wizards, Seers & Healers Myths & Tales by Diane Purkiss