To the Ant & The Ant’s Answer

By Caroline Howard Gilman

Annotations by Kathryn t. burt

To the Ant

Two little girls carried a piece of sugar for some months, every day, from the breakfast table, to a family of ants, and one of them said thus: Come here, little ant, For the pretty bird can't. I want you to come, And live at my home; I know you will stay, And help me to play. Stop making that hill, Little ant, and be still. Come, creep to my feet, Here is sugar to eat. Say, are you not weary, My poor little deary, With bearing that load, Across the wide road? Leave your hill now, to me, And then you shall see, That by filling my hand, I can pile up the sand, And save you the pains Of bringing these grains.

GILMAN, CAROLINE HOWARD. 1850. “To the ant.” IN A GIFT BOOK OF STORIES AND POEMS FOR CHILDREN, 43-44. New York: C.s. Francis & Co. ProQuest American Poetry.

The Ant’s Answer

Stop, stop, little miss, No such building as this Will answer for me, As you plainly can see. I take very great pains, And place all the grains As if with a tool, By a carpenter's rule[1]. You have thrown the coarse sand All out of your hand, And so fill'd up my door, That I can't find it more. My King and my Queen Are chok'd up within; My little ones too, Oh what shall I do? You have smother'd them all, With the sand you let fall. I must borrow or beg, Or look for an egg[2], To keep under my eye, For help by and by, A new house I must raise, In a very few days, Nor stand here and pine[3], Because you've spoilt mine. For when winter days come, I shall mourn for my home; So stand out of my way, I have no time to play.

Gilman, Caroline Howard. 1850. “The Ant’s Answer.” In A Gift Book Of Stories and Poems For Children, 45-46. NEW YORK: C.S. FRANCIS & CO. PROQUEST AMERICAN POETRY.

[1] A specialized ruler used by carpenters that can be folded up.

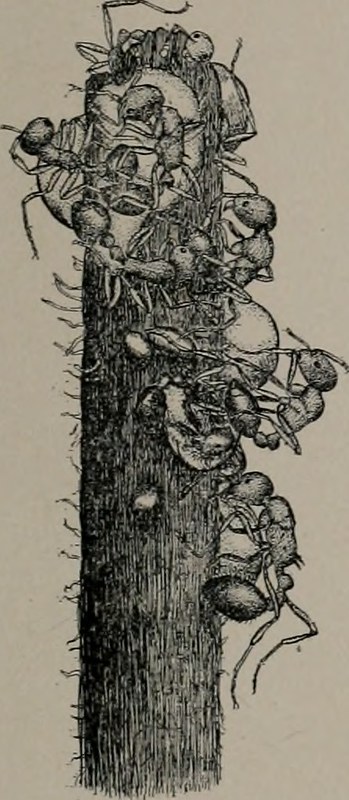

[2] A note from Gilman: “When an ant’s nest is disturbed, there may be seen processions of ants bearing little white eggs, for more than a day. Ants are divided into workers, sentinels, &c., like bees, and they have their King and Queen also.”

[3] To yearn, long, or wish desperately for.

Contexts

In her book, The Poetry of Traveling in the United States, Caroline Howard Gilman expressed ambivalence towards the infrastructural improvements occurring in her town of Charleston, SC. While she recognized “the spirit of utility” in such developments as roads and public walks, she mourned the loss of “spots to verdure and shade, where our children can revel amidst glimpses of nature, instead of struggling through King-Street for sugar plums and ice creams” (33). Howard Gilman also believed that time spent in nature allowed adults and children alike to feel better connected to God, and she urged her readers to take time away from the distractions of the industrialized cities: “Let those who live in cities carry their children, sometimes, to a retreat of idleness; let them pause in the hurry of the locomotive sweep of modern education, and teach them by hillside and rivulet” (158).

Resources for Further Study

- According to Gale L. Kenny, Howard Gilman’s work created for children “an imaginary South that she hoped would be embraced and enacted by her young readers as they grew older” (66). For more about the southern paternalism underlying Howard Gilman’s work, see Kenny’s article “Mastering childhood: Paternalism slavery, and the southern domestic in Caroline Howard Gilman’s Antebellum children’s literature.”

- Gilman, Caroline Howard. 1838. The Poetry of Traveling in the United States. New York: S. Coleman. https://books.google.com/books?id=tggfAAAAMAAJ&vq=nature&source=gbs_navlinks_s.

Pedagogy

In their article, “Learning with Children, Ants, and Worms in the Anthropocene: Towards a Common World Pedagogy of Multispecies Vulnerability,” Affrica Taylor and Veronica Pacini-Ketchabaw argue that children who have encounters with small creatures like ants are more aware of the ‘common world’ they share with other creatures. The authors encourage such interactions and suggest that ant encounters in particular teach children “about the relative power and affect that large and small creatures can exert upon each other” (523). Below are other resources available that can help you facilitate safe interactions between ants and the young people in your life:

- Clark, Hillary. 2019. “Kids & Nature Connections | Explore the interesting world of ants!” Last modified April 10, 2019. https://www.wenatcheeworld.com/lifestyles/family_and_faith/kids-nature-connections-explore-the-interesting-world-of-ants/article_3c92a851-02a1-57fa-a2d8-968ebc47b1f8.html.

- Home Science Tools. n.d. “Ants Science Projects.” Accessed November, 14 2020. https://learning-center.homesciencetools.com/article/ant-science-projects/.