The Sugar Plums

By William Lloyd Garrison

Annotations by Celia Hawley

No, no, pretty sugar-plums! stay where you are!

Though my grandmother sent you to me from so far!

You look very nice, you would taste very sweet,

And I love you right well, yet not one will I eat.

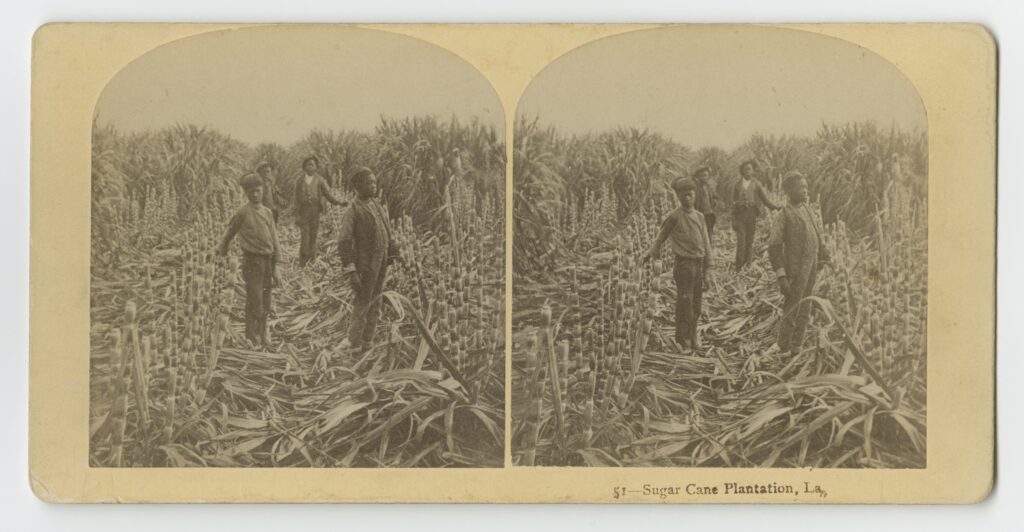

For the poor slaves have labored, far down in the south,

To make you so sweet, and so nice for my mouth!

But I want no slaves toiling for me in the sun,

Driven on with the whip, till the long day is done. [1]

Perhaps some poor slave-child that hoed up the ground,

Round the cane in whose rich juice your sweetness was found, [2]

Was flogged till his mother cried sadly to see,

And I’m sure I want nobody beaten for me.

Thus said little Fanny, and skipped off to play,

Leaving all her nice sugar-plums just where they lay;

As merry as if they had gone in her mouth,

And she had not cared for the slaves in the south. [3]

Garrison, William Lloyed. “The Sugar Plums,” IN Juvenile Poems: For the use of free American children, of every complexion, 18. Boston: Garrison & knapp, 1835.

Contexts

Who Writes for Black Children?: African American Children’s Literature before 1900, Katharine Capshaw and Anna Mae Duane, editors. The book references the Garrison’s Juvenile Poems and includes an excerpt by Garrison in its preface: “If … we desire to see our land delivered from the curse of prejudice and slavery, we must direct our efforts chiefly to the rising generation, whose minds are untainted, whose opinions unfashioned, and whose sympathies are true to nature in its purity.” The editors observe that Juvenile Poems is probably the first American book title that is consciously worded to include all children, regardless of race.

Free Produce Movement: This movement was about boycotting goods produced by slaves in Britain and America, and featured Quakers at its forefront.

Resources for Further Study

- Enterprising Youth: Social Values and Acculturation by Monika Elbert includes Lesley Ginsberg’s essay referencing Garrison’s Juvenile Poems.

- How Sugar Changed the World by Heather Whipps

- Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History by Sidney Mintz

- Smithsonian American Art Museum’s page on Samuel Halpert

Contemporary Connections

PBS Interview: Before cotton, sugar established America’s reliance on slave labor

[1] “Sugar slavery was the key component in what historians call The Trade Triangle, a network whereby slaves were sent to work on New World plantations, the product of their labor was sent to a European capital to be sold and other goods were brought to Africa to purchase more slaves.” Heather Whipps; see resources below.

[2] About sugar cane: “White Gold, as British colonists called it, was the engine of the slave trade that brought millions of Africans to the Americas beginning in the early 16th-century.” Heather Whipps

[3] “The ‘free produce’ movement was a boycott of any goods produced with slave labour. It was seen as a way of fighting slavery by having consumers buy only produce from non-slave labour. The movement was active in North America from the beginning of the abolitionist movement of the 1790s to the end of slavery in the 1860s.” Heather Whipps