The Birds at My Door

By Mary Effie Lee

Annotations by Catherine Bowlin

IF you live in the country, you can have many interesting experiences with birds. One morning, at about seven o’clock, last March, I discovered a fawn-colored screech owl perched disconsolately upon the upper sash of a window which had been left lowered from the top all night. [1] The owl, uttering faint croons, peered about as if trying to discover where he had spent the night. It was many minutes after my finding him, that he fluttered heavily away. My first cry of surprise seemed in no wise to have disturbed him.

Once, at this same window, I found a chimney swift, clinging desperately to the screen. The bird had flown in at the top of the window and landed just inside, against the screen below. He was quivering with fear.

For countless springs, the swifts, or swallows, had taken up their abode in a south chimney of our house. We could hear them often at night, in the brick-walled home. They seemed always to be “cuddling down”, yet never to get quite “cuddled” to their satisfaction. The little bell-like twitterings would be sounding, I imagined, whenever I awoke.

At dusk, when the sky was lavender, the swallows would flutter in graceful groups, trilling, swirling high over our heads. [2] How well I can see them now!––grouping themselves, breaking ranks, then flitting together. But as to having come into close contact with our neighbors, the swifts, that pleasure had not been mine till I found the frightened bird on the window screen. [3]

“Ah, here you are at last, little lodger,” I thought, and my heart bounded as it had when I first discovered an oriole’s nest. “We have slept in the same house many nights,” I said gently. “You should not fear me now.”

But the swallow said, with its every twitch, “Oh, please don’t touch me,––don’t touch me!” [4]

I watched it a minute, before setting it free. Swallows in motion, gnat-catching, are more pleasing to look upon than swallows in repose. When one is clinging to your screen, you think, “What a queer, little, long-winged bird; dark, with here and there touches of weather-beaten-shingle gray; tiny black beak and strange stubby tail, with extended spines that seem to hold it to the screen like black basting threads!”

Rather a mousy-looking little creature, somehow, it seemed to me. Its prominent black eyes appeared to add to the suggestion.

Speaking of bright dark eyes, reminds me of the humming-bird that was imprisoned one August day on my back porch. [5] She––for the little bird lacked the crimson throat that marks the male hummer––frantically imagined herself a captive, till she found that only the west end of the porch was incased in glass, and all the rest consisted of railing and lattice work. But while she was discovering this, I had an opportunity to watch her.

For a long time, I saw only a blinding grayish blur of perpetual motion. Then the hummingbird paused on the framework of the window, and I noticed the sheen on her splendid moss-green feathers, and marvelled at tiny black claws, minute enough to have been fashioned from wire hairpins. I heard a faint, “Chirp, chirp.” Yet, when I was a child, someone had told me that humming-birds made no sound aside from the buzzing produced by their wings in motion.

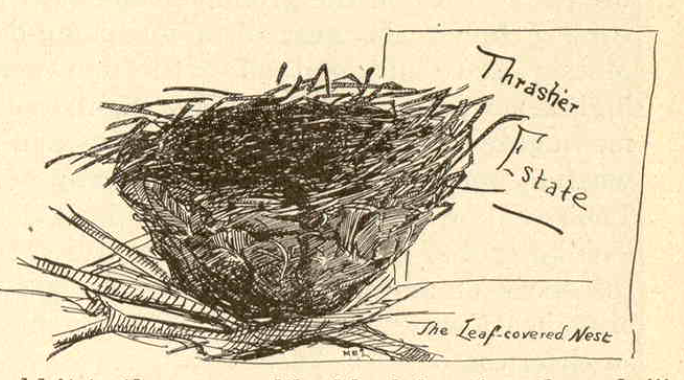

While writing of sounds, I think of a songbird, the brown thrasher, and a surprise that the thrashers once gave me. [6] On a sunny morning in spring, I came upon a pile of brush at the back of the orchard. Peeping at me through the mass of twigs, was a certain old Plymouth Rock hen, that I had always suspected of being a little daft. [7] Her ways were wild and strange. She delighted in hatching eggs in outlandish places. I went to discover upon what she was sitting. And what do you think I beheld just above Mrs. Plymouth Rock? I found a brown thrasher there, nesting complacently in what you might call the second story of the brush heap. Her glassy yellow eyes glared at me coldly, as if to say, “If it suits Mrs. Plymouth Rock and me–––”

But who can account for the whims of birds? One summer day, a most amazing sight met my eyes. Flat on the ground in the back pasture, I found the nest of a mourning-dove! [8] Mother Dove fluttered off, with that gentle, high-keyed plaint that she uses in flight, and left me to gaze at the nest of faded rootlets and two woefully ugly fledglings with long gray breaks. Their shallow nest was on a particularly damp-looking spot of earth. After one recovered from the little shock of finding the brood on the ground, one’s heart was filled with pity. The sight was so cheerless. [9]

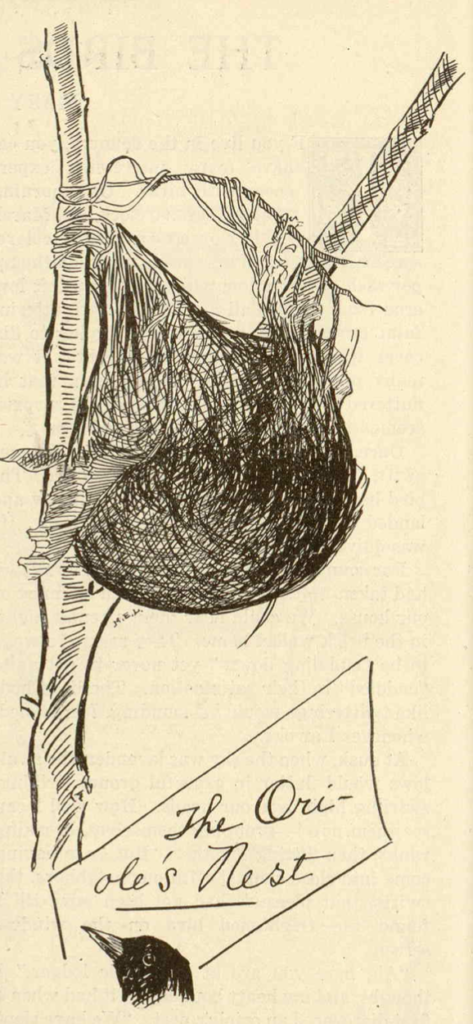

I thought of the oriole’s comely basket, high in the golden light, where it swung from the tip of a poplar branch. [10] I thought of a neat song-sparrow’s nest that I had just seen hidden under the “eaves” of a Norway spruce hedge, where the song-sparrows spend the winter.

They come out on every mild morning to sing a little, even when Cardinal is silent. You recall their sharp knife-like notes. Ever ready to make cheer, the song-sparrows would seem to live a life free from trouble. Yet they know what it is to have their hedge haunted by wily cats, on winter evenings, when the cold birds are fluttering to shelter; and at dusk, in spring, when Mother Sparrow is directing her awkward, freckled birdlings to some nook for safety. [11]

Oh, I cannot tell how indignant it made me once to discover in the nest of Mother Song-Sparrow, two cowbird eggs, flecked with cocoa-brown like hers, but a trifle larger. Unsuspecting little Song-Sparrow, would have five instead of three eggs to tend, while the cowbird went swaggering with her noisy comrades up and down the pasture, in the wake of the cows.

As I write, this pasture is white with snow. For it is a January day, and cold. Five crows have come up from the woods, to peck at the corn stubble in what was once a pasture and then a cornfield. They strut over the snowy surface and pull at the bits of stalk. But they never come to feast when I feed Titmouse, with his golden hoard under each wing, and Chickadee, wearing the jaunty black skullcap, and making small sounds like corks screwing in bottles. [12]

Lee, Mary Effie. “The Birds at My Door.” The Brownies’ Book, ed. W. E. B. Du Bois, vol. 1, no. 4, New York, N.Y.: DuBois and Dill, April 1920. 105-106. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/22001351/>.

Contexts

This nonfiction text blends both animal welfare and natural history. Lee describes and animates many different types of birds, but important to note is Lee’s evocation of readers’ sympathy. The young author “anthropomorphizes and feminizes” the animals throughout the text as a way to teach moral lessons to her young readers (Kilcup 306, full citation below). Lee’s nonfiction demonstrates her ability to write informally and with a child-like tone, while also drawing important and mature connections about animal welfare.

Resources for Further Study

- The Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Birds of the World: All About Birds

- Kilcup, Karen. Stronger, Truer, Bolder: American Children’s Writing, Nature, and the Environment. University of Georgia Press, 2021.

[1] Either a Western Screech-Owl or an Eastern Screech-Owl

[2] There are many kinds of Swallows, including Tree, Barn, Cave, Bank, Cliff, etc.

[3] Again, many types of Swifts, including Chimney, Vaux’s, Black, White-throated, Violet-green, etc.

[4] Lee anthropomorphizes the swallow here.

[5] Types of Humming-birds: Anna’s, Lucifer, Rufous, Rivoli’s, Costa’s, etc.

[6] The Brown Thrasher is difficult to see in brush as its coloring blends in.

[7] An American breed of a domestic chicken.

[8] The Mourning-Dove is a graceful and common bird in the US.

[9] Here, Lee evokes sympathy from her readers.

[10] Many types of Orioles, including Baltimore, Orchard, Hooded, Scott’s, Audubon’s, etc.

[11] Lee draws attention to the birds’ vulnerability during the winter season.

[12] Types of Titmouse: Tufted, Bridled, Juniper, etc. & types of Chickadee: Carolina, Mountain, Boreal, etc.