The Dog and the Clever Rabbit

By A. O. Stafford

Annotations by Rene Marzuk

There were many days when the animals did not think about the kingship. They thought of their games and their tricks, and would play them from the rising to the setting of the sun.

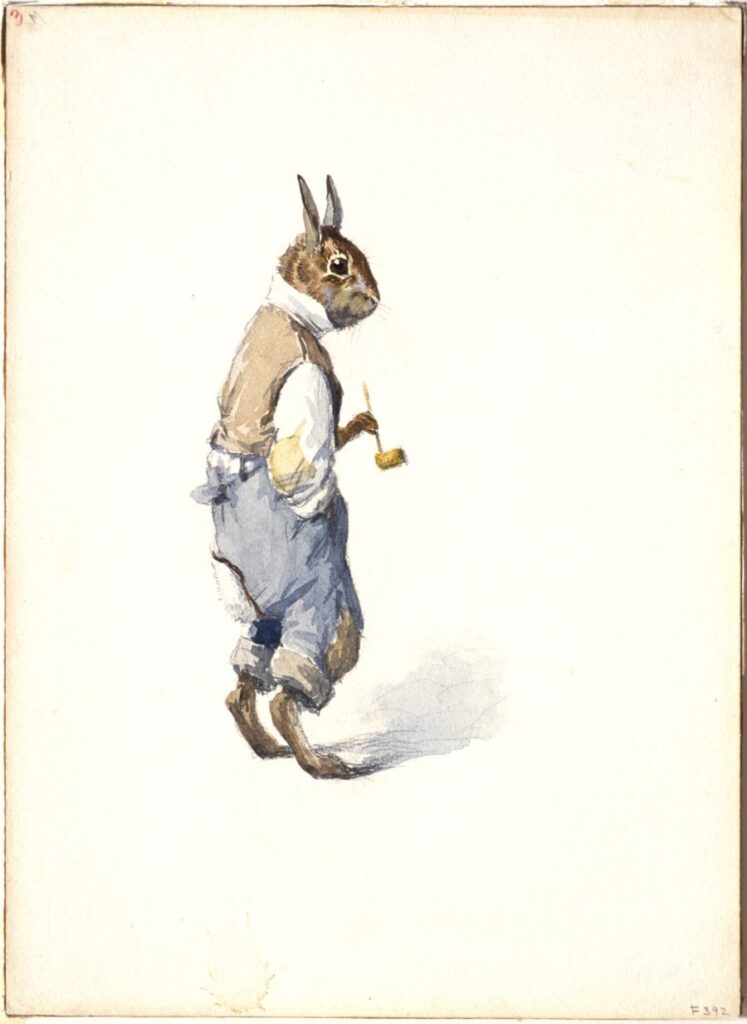

Now, at that time, the little rabbit was known as a very clever fellow. His tricks, his schemes, and his funny little ways caused much mischief and at times much anger among his woodland cousins.[1]

At last the wolf made up his mind to catch him and give him a severe punishment for the many tricks he had played upon him.[2]

Knowing that the rabbit could run faster than he, the wolf called at the home of the dog to seek his aid. “Brother dog, frisky little rabbit must be caught and punished. For a nice bone will you help me?” asked the wolf.

“Certainly, my good friend,” answered the dog, thinking of the promised bone.

“Be very careful, the rabbit is very clever,” said the wolf as he left.

A day or so later while passing through the woods the dog saw the rabbit frisking in the tall grass. Quick as a flash the dog started after him. The little fellow ran and, to save himself, jumped into the hollow of an oak tree. The opening was too small for the other to follow and as he looked in he heard only the merry laugh of the frisky rabbit, “Hee, hee! hello, Mr. Dog, you can’t see me.”

“Never mind, boy, I will get you yet,” barked the angry dog.

A short distance from the tree a goose was seen moving around looking for her dinner.

“Come, friend goose, watch the hollow of this tree while I go and get some moss and fire to smoke out this scamp of a rabbit,” spoke the dog, remembering the advice of the wolf.

“Of course I’ll watch, for he has played many of his schemes upon me,” returned the bird.

When the dog left, the rabbit called out from his hiding place, “How can you watch, friend goose, when you can’t see me?”

“Well, I will see you then,” she replied. With these words she pushed her long neck into the hollow of the tree. As the neck of the goose went into the opening the rabbit threw the dust of some dry wood into her eyes.

“Oh, oh, you little scamp, you have made me blind,” cried out the bird in pain. Then while the goose was trying to get the dust from her eyes the rabbit jumped out and scampered away.

In a short while the dog returned with the moss and fire, filled the opening, and, as he watched the smoke arise, barked with glee, “Now I have you, my tricky friend, now I have you.” But as no rabbit ran out the dog turned to the goose and saw from her red, streaming eyes that something was wrong.

“Where is the rabbit, friend goose?” he quickly asked.

“Why, he threw wood dust into my eyes when I peeped into the opening.” At once the dog knew that the rabbit had escaped and became very angry.

“You silly goose, you foolish bird with web feet, I will kill you now for such folly.” With these words the dog sprang for the goose, but only a small feather was caught in his mouth as the frightened bird rose high in the air and flew away.

Stafford, A. O. “The Dog and the Clever Rabbit,” IN THE UPWARD PATH: A READER FOR COLORED CHILDREN, ED. MYRON T. PRITCHARD AND MARY WHITE OVINGTON, 109-12. HARCOURT, BRACE AND HOWE, 1920.

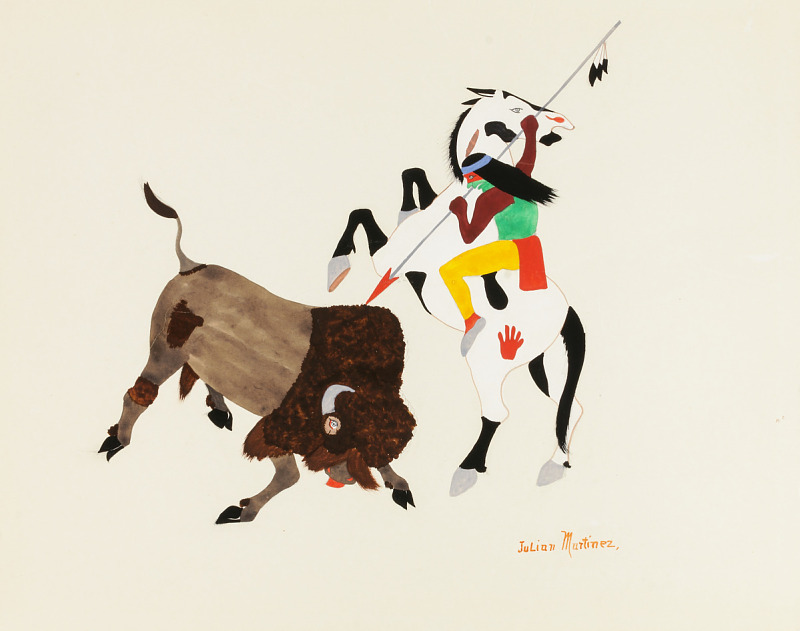

[1] Rabbits are usually trickster characters in African, African-American, and Native American Culture. Br’er Rabbit, for example, is a trickster that recurs in many stories from the oral traditions of enslaved communities from the Southern United States.

[2] There are three recognized species of American wolf: the gray wolf, the eastern wolf, and the American red wolf.

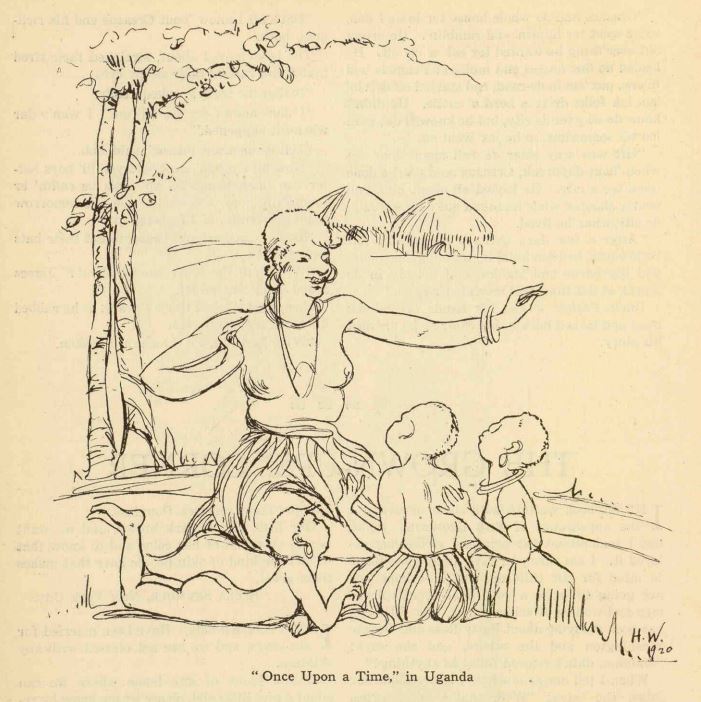

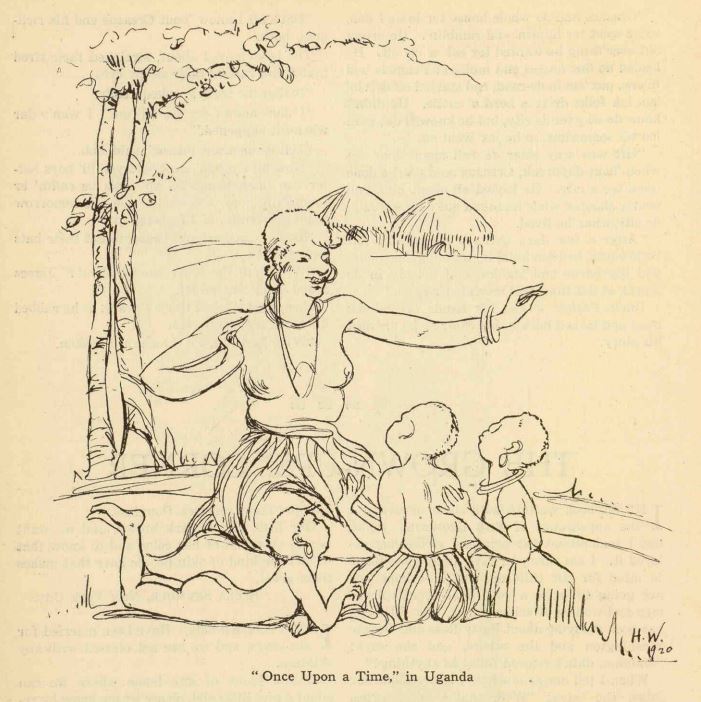

Contexts

This short story was included in The Upward Path: A Reader for Colored Children, published in 1920 and compiled by Myron T. Pritchard and Mary White Ovington. The volume’s foreword states that, “to the present time, there has been no collection of stories and poems by Negro writers, which colored children could read with interest and pleasure and in which they could find a mirror of the traditions and aspirations of their race.”

Definitions from Oxford English Dictionary:

- scamp: A good-for-nothing, worthless person, a ne’er-do-well, “waster”; a rascal. Also playfully as a mild term of reproof.

Resources for Further Study

- Overview of tricksters in African American literature..