Fishes at Work

By Rhoda Little

Annotations by Kristina Bowers

In a late number of THE LITTLE CORPORAL, is an interesting description of “fishes at play.” The sight was wonderful and rare, and few of those who read the account, will ever see the like; but many of us may watch fishes at work, without going to the sea. For fishes do work, and I have often seen them.

On some parts of the Island of Aquidneck[1], where I live, the shores are marshy, with fresh streamlets, here and there, meandering down to the salt water.

There is one marsh in particular, at the edge of the bay, with still pools sunk in the peaty[2] soil. These are filled partly by rain, from the clouds, and partly by the sea, that sometimes overflows them at spring tides. Coarse grass droops around their margins, forming dark, sheltered recesses among its roots; while sea lettuce[3], and other marine plants, float in broad, green patches on the surface of the brackish water. Every spring, scores of little fishes find their way into these pretty lakelets, and lay their eggs, or, as we commonly say, spawn, in their quiet water.

Many an hour, from March to June, do I spend in watching their attractive ways, as, all unconscious of observers, they carry on their busy housekeeping.

My favorite, among them, is the two-spined stickleback. It is only two or three inches long, sharp nosed, straight backed, flat sided, rough tailed, and bony; with spines about it; the two upon its back as big and sharp as the prickles upon a gooseberry bush. Yet it is beautiful. Both male and female are green and brown above, and silvery below, with great, round eyes; but the male is much the handsomer of the two. His colors are deeper, and there are times when his cheeks and sides become of a brilliant red.

While the sun has shone through many long days, and the water is warm and clear, the sticklebacks know it is time to get ready a lodging for their eggs. The male finds his mate, and, side by side, the pair swim up and down, seeking a convenient place. Sometimes a whole day is spent, in searching about, and holding consultations.

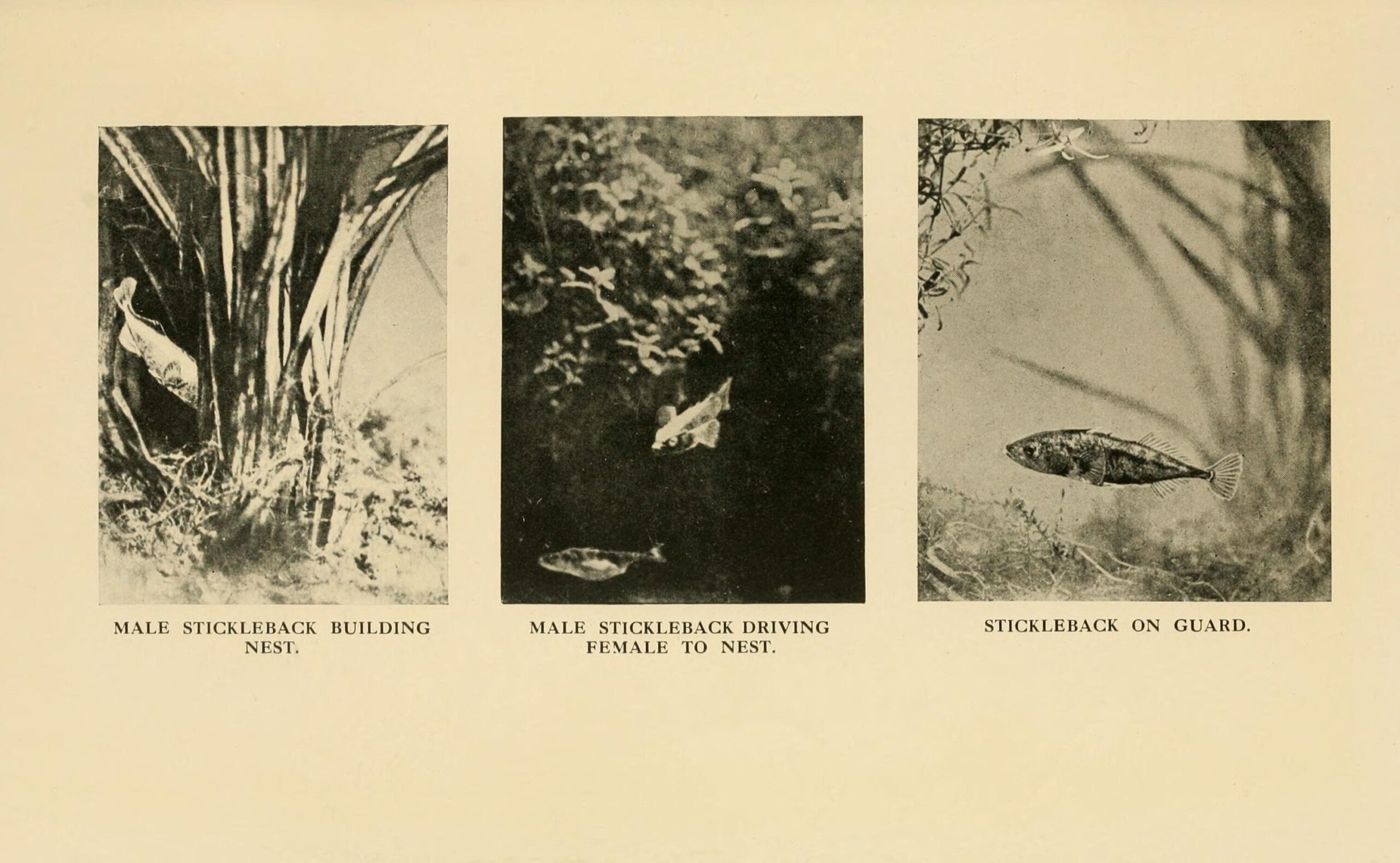

At last, a spot is chosen, somewhere upon the bottom, and the male sets to work. He begins by clearing off whatever sticks, or other rubbish, may be in the way, carrying each bit to a distance. Then he takes away the sand, a mouthful at a time, until he has formed a hollow, of the size and shape of a watch crystal[4].

Sometimes a fragment of shell, or stone, sticks up, and the little fellow has to tug long and hard, to remove it.

When the nest is deep enough, he lines it with fronds of hollow-weed, sea lettuce, or some other smooth plant. These he cuts with his teeth, and lays the strips, one by one, strewing a little sand upon each, to keep it from being brushed aside. When the bottom of the nest is covered with a layer of strips, all lying one way, he spreads another layer across it, with all the pieces lying the other way, making a soft, even mattress. Often, he sinks down upon this bed, and presses it with his breast, fluttering his wing-like fins, much like a hen canary bird, when lining her nest.

All the while he is at work, his mate sails up and down, encouraging him by her presence, but taking no part in his toil. Every now and then, he swims swiftly toward her, and insists on her coming to see the nest. She does so willingly, bending down, and looking at it with silent approval.

Sometimes, she wanders in search of food, and gets out of sight. He does not always miss her at once, but when he does, you should be there to see. He drops his precious piece of silky frond, no matter how carefully he has shaped it; he quits the nest, and, like one bereft[5] of common sense, rushes wildly about, as if all his aims in life were lost. When he finds the unwitting truant, he seems to chide her, and with impetuous[6] haste, drives her back to the scene of his labors.

Calm and serene herself, she cannot share his frenzy; but she gently gives up her own will to his, although she sees no reason for his perturbation[7]. Then he forgets his fears, forgives the cause, and resumes his task.

Now and then he stops work for a few minutes and has a little frolic with his mate. They affect to bite each other, and lay their heads across each other’s necks, like friendly horses in a field. They swim, side by side, in narrow circles; they chase each other, rising one above the other in pursuit, like swallows sporting in the air.

Two days, or more, pass thus, and at last the nest is ready, and the eggs are in it.

Then the careful stickleback makes haste to cover them. Working more mightily than ever, he brings frond after frond of some delicate water plant, and spreads over them. Crossing these as before, he takes no rest while a chink remains, through which can be seen a single egg.

He goes further, and piles on more leaves, with so ingenious a show of carelessness, that no boy or girl would ever suspect that beneath his little patch of shredded weeds, there was hidden a fish’s cradle.

The stickleback’s tasks are not yet ended. He has other work to do. Some rude intruder may meddle with his charge. He must not leave it.

Accordingly, he sets himself to watch. All day he sails up and down, and round about, feeding scantily upon such morsels of food as drift within his beat; never losing sight of the nest.

All night he hovers above it, even sleeping with so much wakefulness as to be roused to vehement[8] action by the slightest stir in the water. If a strolling crab chances to sidle by, he rushes headlong upon it, and bites madly at its defenceless[sic] eyes. If an eel wriggles near, he erects his horrid spines, and dashes furiously against it, threatening to tip it up with these double daggers. He darts with the speed of lightning. The irides of his eyes, his cheeks, his sides, glow with vivid scarlet.

No foe dares resist him, but every one makes haste to quit the field.

For three weeks, this faithful sentinel keeps guard. Toward the close, his vigilance increases. He often draws very near the nest, and peers closely. Sometimes he touches it with his nose; puts down his head, as if listening.

Suddenly, he acts as if he had gone mad. He seizes the loose, outer covering, that served as a screen, and scatters the pieces right and left. He tears open the inner coverlid, that he had so carefully felted. He hangs breathless above the nest. What does he expect?

Presently, there issues from the rents[9], a train of fifty to a hundred tiny creatures, no bigger than midges[10], with filmy, transparent bodies, and wide, staring eyes.

The eggs have hatched, and these are the baby sticklebacks. They swim away, and the father’s work is done.

There is something beautiful in all this toil and watching, and anxiety, and bravery, and patience, of the little two-spined stickleback.

It is not for himself; it is wholly for others; for little ones that are to appear before him for a moment, and pass out of his sight, to be known no more.

When we see the self-devotion, that the Maker of us all has taught this humble fish shall we waste our higher lives in self pleasing? Let us rather learn from these lowly dwellers of the pool, that His works and His word teach the same lesson: Live for others, and not for yourselves.

Little, Rhoda. “Fishes at Work.” The Little Corporal: An Illustrated Magazine for Boys and Girls. 12, No. 6 (June 1871): 205.

[1] Aquidneck Island, also known as Rhode Island, is located in Narragansett Bay in the state of Rhode Island.

[2] Peat: Partially decomposed vegetable tissue. (Merriam-Webster)

[3] Sea Lettuce: Marine green algae sometimes eaten in salad or soup. (Merriam-Webster)

[4] Watch crystals are approximately 12 to 57 mm.

[5] Bereft: Lacking. (Merriam-Webster)

[6] Impetuous: Impulsive vehemence or passion. (Merriam-Webster)

[7] Perturbation: State of being upset, bothered. (Merriam-Webster)

[8] Vehement: Intensely emotional, passionate. (Merriam-Webster)

[9] Rent: An opening made by rending or splitting. (Merriam-Webster)

[10] Midge: A tiny fly. (Merriam-Webster)

Contexts

The many varieties of the stickleback fish have a mating ritual that is accurate to the one described in this essay. The Encyclopedia Brittanica describes the mating as “highly ritualized.” The male stickleback takes a large role in building and guarding the next as well as parenting the young once they’ve hatched. [1]

Resources for Further Study

- “In stickleback fish, dads influence offspring behavior and gene expression” from The Illinois News Bureau.

- Information on sticklebacks from the Pennsylvania Fish & Boat Commission.