Instincts of Childhood.

A Dialogue in Two Parts.

By John Neal

Annotations by Celia Hawley

Scene I. – A large room in a country home. Mrs. Nevers seated, engaged in sewing. – Margaret standing by an open window, shaded with grape vines and honeysuckles. A bird cage containing several birds, hangs near. Margaret (after watching the motions f the mother-bird for some time.)

Margaret. There, now! – there you go again! you little foolish thing, you! Why, what is the matter with you? I should be ashamed of myself! I should so! Hav’nt we bought the prettiest cage in the world for you? Hav’nt you enough to eat, and the best that could be had, for love or money – sponge cake, loaf sugar, and all sorts of seed? Did’nt father put up a little nest for you with his own hands; and hav’nt I watched over you, you little ungrateful thing? – till the eggs they put there had all turned to birds – little live birds, no bigger than grasshoppers, and so noisy, ah, you can’t think? Just look at the beautiful clear water there – and the clean white sand. Where do you think you could find such water as that, or such a pretty glass dish – or such beautiful bright sand, if we were to take you at your word, and let you out with that little nest full of young ones, to shift for yourselves, hey?

[The door opens, and Mr. Nevers enters.]

Mar. O father, I’m so glad you’ve come! What do you think is the matter of poor little birdy?

[The father looks down among the grass and shrubbery, and up into the top branches, and then into the cage – the countenance of Margaret growing more and more perplexed, and more sorrowful every moment.]

Mar. Well, father – what is it? Does it see anything?

Mr. N. No, my love – nothing to frighten her; but where is the father-bird?

Mar. He’s in the other cage. He made such a to-do when the little birds began to chipper this morning, that I was obliged to let him out; and brother Bobby he frightened him into the other cage, and carried him off.

Mr. N. Was that right, my love?

Mar. Why not father? He wouldn’t be quiet here, you know, and what was I to do?

Mr. N. But, Moggy, dear – those little birds may want their father to help feed them; the poor mother bird may want him to help take care of them – or to sing to her.

Mar. Or perhaps show them how to fly, father?

Mr. N. Yes, dear. And to separate them just now – how would you like to have me carried off, and put into another house, leaving nobody at home but your mother to watch over you and the rest of my little birds?

[Margaret muses a few moments, and then returns to the original subject.]

Mar. But, father, what can be the matter with the poor thing? – you see how she keeps flying about, and the little ones trying to follow her – and tumbling upon their noses – and toddling about is if they were tipsy, and could’nt see straight.

Mr. N. I am afraid she is getting discontented.

Mar. Discontented! how can that be, Father? Has’nt she her little ones about her, and every thing on earth she can wish? And then, you know, she never used to be so before?

Mr. N. When her mate was with her, perhaps.

Mar. Yes, father – and yet, now I think of it, the moment these little wretches began to pee-peep, and tumble about so funny, the father and the mother both began to fly about the cage, as if they were crazy. What can be the reason? The water, you see, is cool and clear; the sand all bright: they are out in the open air, with all the green leaves blowing about them; their cage has been scoured with soap and sand, the fountain filled, and the seed-box – and – and – I declare, I cannot think what ails them!

Mr. N. My love – may it not be the very things you speak of, things which you think ought to make them happy, are the very cause of all the trouble you see? The father and mother are separated! How can they teach their young to fly in that cage? How teach them to provide for themselves?

Mar. But father – dear father -! [laying her little hand upon the spring of the cage door] dear father, would you?

Mr. N. And why not, my dear child? [He stoops and kisses her.] Why not?

Mar. I was only thinking, father. If I should let them out, who will feed them?

Mr. N. Who feeds the young ravens, dear? Who feeds the ten thousand little birds that are flying about us now?

Mar. True, father; but they have never been imprisoned, you know, and have already learned to take care of themselves!

Mrs. N. [looking up and smiling,] Worthy of profound consideration, my dear – I admit your plea, but have a care, lest you over-rate the danger and the difficulty in your unwillingness to part with your beautiful little birds.

Mar. Father – [she throws open the door of the cage.]

Mr. N. Stay, my child? What you do must be done thoughtfully, conscientiously, so that you may be satisfied with yourself hereafter, when it is all over. Shut the door a moment, and allow me to hear all your objections.

Mar. I was thinking, father, about the cold rains, and the long winters, and how the poor birds that have been so long confined would never be able to find a place to sleep in, or water to wash in, or seeds for their little ones.

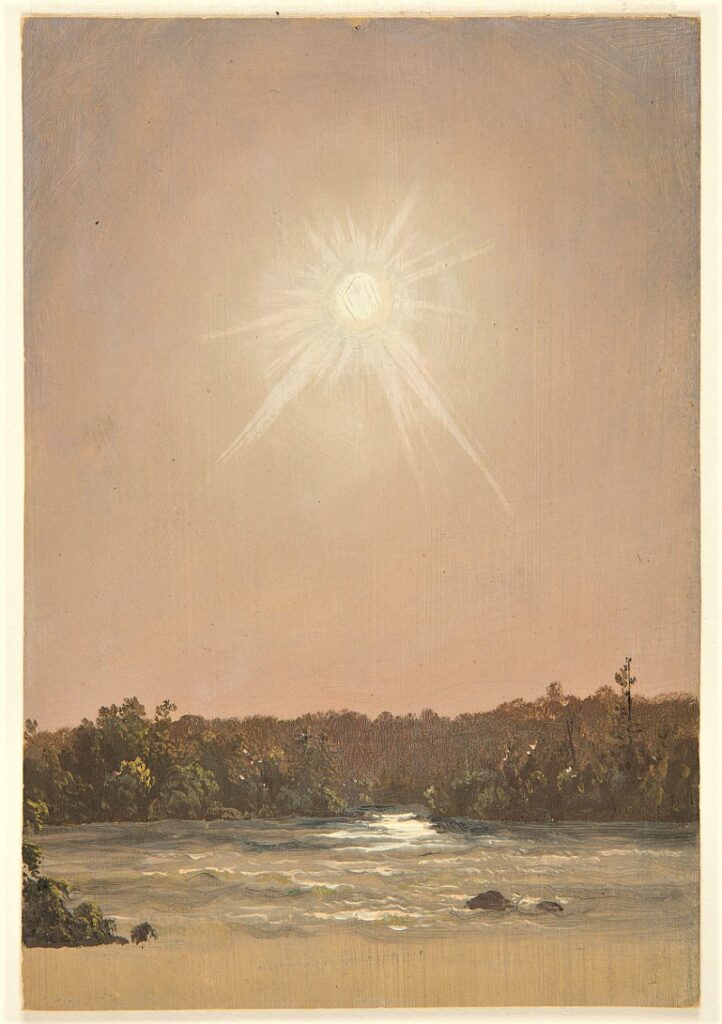

Mr. N. In our climate, my love, the winters are very short: and the rainy season itself does not drive the birds away; and then you know birds always follow the sun – if our climate is too cold for them, they have only to go farther south. But in a word, my love, you are to do as you would be done by. As you would not like to have me separated from your mother and you; as you would not like to be imprisoned for life, though your cage were crammed with loaf sugar and sponge cake – as you – –

Mar. That’ll do, father! That’s enough! Brother Bobby! Hither, Bobby! Bring the little cage with you – there’s a dear.

Scene II. – Evening, Mrs. Nevers and Margaret seated – Enter Mr. N speaking loud as he comes forward.

Mr. N. The ungrateful hussey! [1] What! After all that we have done for her; given her the best room we could spare – feeding her from our own table – clothing her from our own wardrobe – giving her the handsomest and shrewdest fellow for a husband within twenty miles of us – allowing them to live together till a child is born; and now, because we have thought proper to send him away for a while, where he may earn his keep – now forsooth! We are to find my lady discontented with her situation.

Mar. Dear father!

Mrs. N. – Hush, child!

Mr. N. – Ay, discontented – that’s the word – actually dissatisfied with her condition! The jade! – with the best of everything to make her happy; confits and luxuries she could never dream of obtaining were she free tomorrow – and always contented till now.

Mar. -And what does she complain of, Father?

Mr. N. – Why, my dear child, the unreasonable thing complains just because we have sent her husband away to the other plantation for a few months: he was getting idle here, and might have grown discontented, too, if we had not packed him off. And then instead of being happier, and more thankful – more thankful to her Heavenly Father, for the gift of a man child, Martha tells me that she has just found her crying over it, calling it a little slave, and wishing the Lord would take it away from her – the ungrateful wench! When the death of that child would be two hundred dollars out of my pocket, every cent of it! [2]

Mrs. N. – After all we have done for her, too!

Mr. N. – I declare I have no patience with that jade!

Mar. Father – dear father!

Mr. N. – Be quiet, Moggy, don’t teaze me now.

Mar. – But father – [she draws her father to the window and points to the cage which still hangs there with the door wide open. He understands her and blushes – then speaks confusedly.]

Dear father! Do you see that cage?

Mr. N. – There go, be quiet, you are a child now, and must not talk about such matters until you have grown older.

Mar. – Why not, father?

Mr. N. – Why not! – Why, bless your little heart! – Suppose I were silly enough to open my doors and turn the poor thing adrift with her child at her breast – what would become of her? Who would take care of her? – who feed her?

Mar. – Who feeds the young ravens, father? Who takes care of all the white mothers, and the white babies we see?

Mr. N. – Yes, child – but then – I know what you are thinking of; but then – there’s a mighty difference, let me tell you, between a slave mother and a white mother – between a slave child and a white child.

Mar. – Yes, father.

Mr. N. – Don’t interrupt me: you drive every thing out of my head. What was I going to say? – Oh – ah! that in our long winters and cold rains, these poor things who have been brought up in our houses, and who know nothing about the anxieties of life, and have never learned to take care of themselves – and – a- a-

Mar. – Yes, father; but could’nt they follow the sun, too? Or go farther south?

Mr. N. – And why not be happy here?

Mar. – But, father – dear father? How can they teach their little ones to fly in a cage?

Mrs. N. – Child, you are getting troublesome!

Mar. – And how teach their young to provide for themselves, father!

Mr. N. – Put the little imp to bed, directly – do you hear!

Mar. – Good night, father! Good night, mother – Do AS YOU WOULD BE DONE BY!

Instincts of Childhood. A dialogue in two parts by John Neal, 1842. (Subscription required)

Contexts

Fielder, Brigitte Nicole. Animal Humanism: Race, Species, and Affective Kinship in Nineteenth-Century Abolitionism. American Quarterly 65, no. 3 (Sept 2013), 487-514. The relationship between animal texts and anti-slavery activism, excerpts follow:

“Children’s literature against animal cruelty and children’s abolitionist literature are related both historically, through the overlapping social movements for abolitionism and animal welfare in the United States and England, and generically, in their shared sentimental approaches to evoking readerly sympathy.17 Before the animal welfare movement reached full speed in the late nineteenth century, the similarities of abolitionist and animal welfare rhetorics were visible in antebellum texts that emphasized the relation between how people treat

animals and how they might treat other people.”

“The idea that certain kinds of animals ought not to be kept captive abounds in Northern antebellum children’s literature, and the similarities between abolitionist and anti–animal captivity stories make [these] texts … look very much like other abolitionist writing. While these poems might very well be read as animal welfare literature, they have been commonly regarded as abolitionist texts.26 The animals in these poems stand in for, or appear interchangeable with, enslaved people: their condition of captivity alludes to the similar condition of enslaved African Americans in the 1830s and 1840s … .”

See also in this volume: The Misfortunes of a Yellow Bird.

Children’s Literature of the 19th Century – It included much orally transmitted material and was often written with a lesson or moral, to instruct.

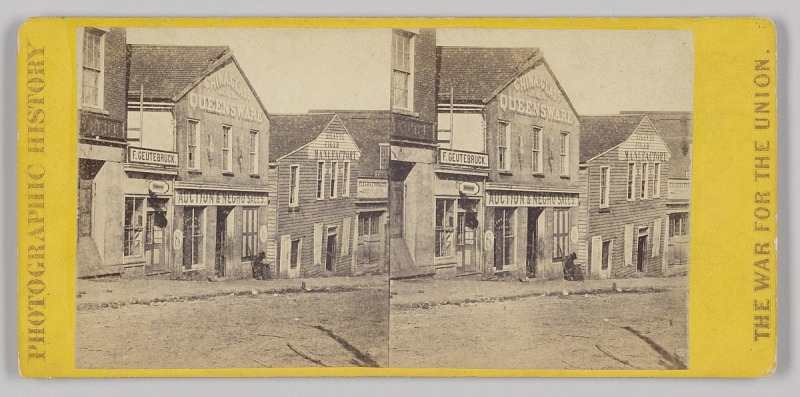

How Slavery Became the Economic Engine of the South by Greg Timmons.

Deep Racism: The Forgotten History of Human Zoos Throughout the late 19th century, Africans and sometimes Native Americans were kept as exhibits at zoos.

Resources for Further Study

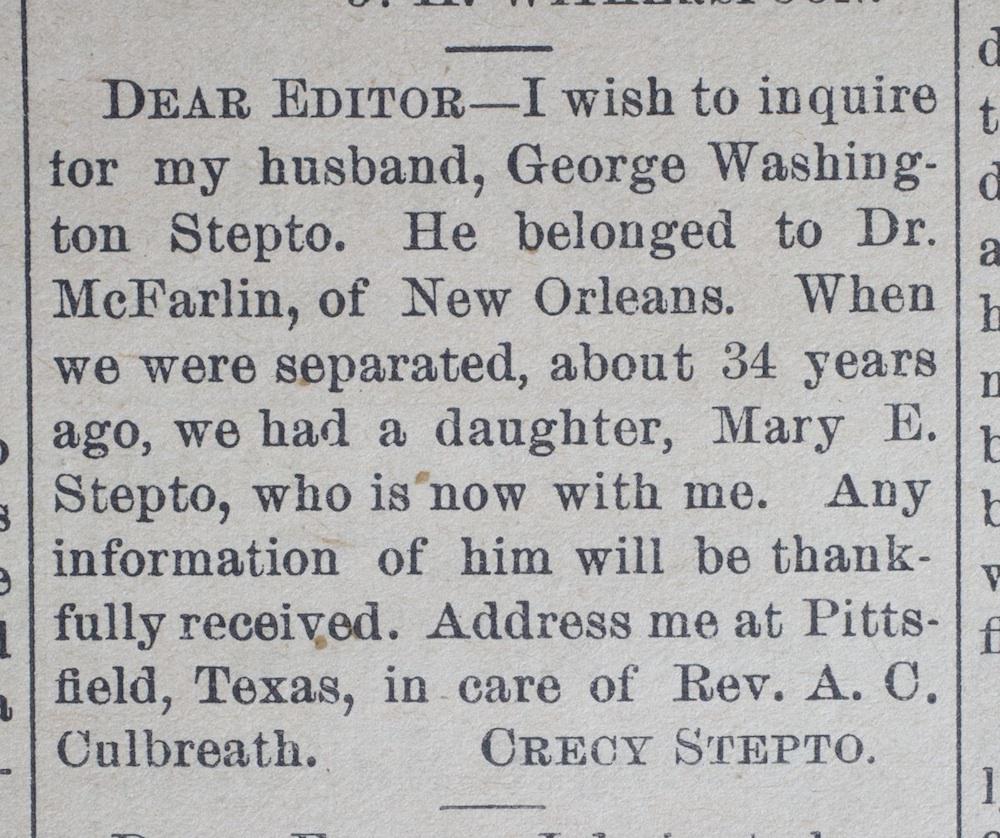

- Enslaved Couples Faced Wrenching Separations.

- Slave Marriages, Families Were Often Shattered by Auction Block, NPR interview for Black History Month.

Pedagogy

- Why do you think the author chose to use a dialogue, or dramatic format, to relate his story?

- You have heard the saying “Do as I say, not as I do.” How is that relevant in the play above?

- A cage is a common symbol of prison or restricted movement. Discuss the use of symbol and metaphor in this piece.

Contemporary Connections

[1] Hussye, jade, wench archaic; derogatory

[2] “Enslaved workers represented Southern planters’ most significant investment and the bulk of their wealth.”

Source: Greg Timmons, below