Ladybirds

By Marie Estelle

Annotations by Kristina Bowers

My Dear Little Corporal: No double you have often taken upon your hand the pretty, little, pink-and-black-spotted beetle called the ladybird, or ladybug, and after admiring its beauty to your satisfaction, attempted to hasten its flight by the alarming information,

“Ladybird, ladybird, fly away home,

Your house is on fire, your children will burn!”

Do you know how that curious couplet came into use? Its origin is probably this: In England and other European countries, the ladybird larvæ, or young, feed principally upon the aphides[sic], or plant lice, which infest the hop vines; and when, in spite of the efforts of the ladybirds, these aphides multiply excessively in the hop gardens,[1] the usual remedy is to let a fire run through the latter, and thus burn up leaves, plant lice, ladybird larvæ, and all. It was their acquaintance with this practice, which, many generations ago, suggested to children of those countries the warning lines now so familiar on both sides of the ocean.

The ladybirds, although such small and inconspicuous insects, have received very great distinction and honor. Their very names – ”Ladybird,” “Ladybug,” “Our Lady’s Key Maid,” “Lady Cow,” etc., are designed to recall their dedication to the Virgin Mary,[2] and by many of the associations and superstitions connected with them, which prevail in northern Europe, we are reminded of the worship of the “sacred beetles”[3] by the ancient Egyptians.

They are relied upon to foretell various kinds of happiness and prosperity, by the circumstances under which they are seen, or the manner in which they take flight after certain mysterious words have been repeated over them. In Germany, where they are great favorites, they are usually connected with the weather. Mr. Cowan, in a very entertaining book called “The Curious History of Insects,”[4] tells us that at Vienna, the children throw them into the air crying,

“Little birdie, birdie,

Fly to Marybrun

And bring us a fine sun.”

Marybrun being a town not far distant from the Austrian capital, where there was an image of the Virgin supposed to be capable of working miracles, the little beetles were sent, with all faith in their power, to solicit good weather from their patroness in behalf of the “merry Viennese.”

Everywhere in Europe, it is considered a good omen to see ladybirds, and extremely unlucky to kill them.[5] (How daring the professional bug hunters must be in those circumstances!) In earlier times, they were also much used in medicine. There was no remedy, we are told, for toothache, equal to ladybirds; one or two of them being crushed and placed in the hollow of the aching tooth, were said to relieve the pain instantly.[6]

The predictions made by means of these beetles regarding the crops, have a foundation in well-known facts; for their aid is often invaluable in destroying the insect foes of certain grains, fruits and vegetables, and if the ladybirds are numerous, it is quite safe to foretell that they will keep the plants clear of aphides and the like, and consequently the harvest will be abundant in proportion. Within the last few years they have been discovered to be the most formidable enemy of our destructive Colorado potato beetle.[7]

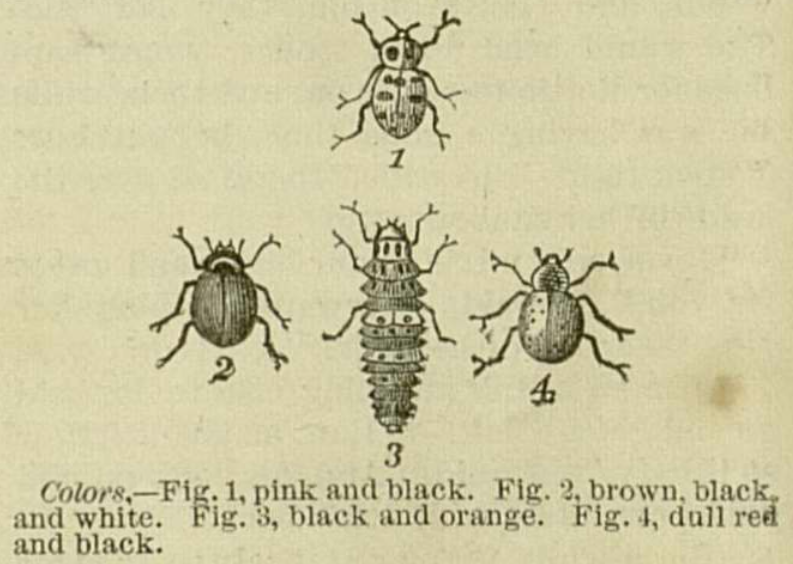

There are, in all, about one thousand different species of ladybirds, and as they are, for the most part cannibals, it will be seen that they rid us every year of vast numbers of insect pests. Their larvæ are very voracious, ugly-looking little creatures, in color dark brown or black, spotted with orange, and roughened with small tubercles[8] and spines. When full grown, they are rather more than one-third of an inch in length, and are very active in securing their prey and eluding capture. Figure 3, in the accompaning [9] illustration, may be taken as a type of the larvæ of several of the best-known species. When ready to undergo transformation, the larva fastens itself at one end, with some gluey substance, to a stem or leaf; the larva skin then gradually wrinkles up and hardens, and is retained as a protection to the pupa within. It does not long remain quiescent,[10] for the beetle issues in seven or eight days. It is in the perfect state that they pass the winter, sheltering under loose bark of trees, in crevices of buildings and fences, under fallen leaves, etc.

In the spring, as soon as the herbage appears, and plant lice and potato beetles begin their depredations,[11] the ladybirds are ready for a fresh attack. Thus we see that aside from their beauty, there are good reasons why they should be guarded from injury and treated with consideration.

In our illustration, fig. 1, at the top, represents, somewhat magnified, the ladybird with which we are all of us most familiar. Its scientific name is Hippodamia maculata. Fig. 4, of the right of the larva, is its nearest relative, H. convergens. Fig. 2, is the smooth, brown ladybird, Coccinella munda, often seen in the fall on composite plants.

Besides their other distinctions, ladybirds are among the few insects that have had the honor of stirring the poetic fancy, owing probably to the superstitions which attracted attention to them. Hurdis[12] devoted quite a long dialogue in one of his dramas to the description of the appearance and virtues of a ladybird; and Southey immortalized the same insect under the name of the “Burnie Bee,”[13] in two fine stanzas, with which I will close this little history.

“Back, o’er thy shoulder throw thy ruby shards, With many a tiny coal-black freckle decked; My watchful hand thy footsteps shall protect. “So shall the fairy train, by glowworm light, With rainbow tints thy folding pennous fret,[14] Thy scaly breast in deepest azure dight, Thy burnished armor decked with glossier jet.”

Estelle, Marie. “Ladybirds.” The Little Corporal: An Illustrated Magazine for Boys and Girls; 12, no. 3(March 1871): 99.

[1] Hop gardens: Hops have been historically grown as a mild sedative and were added to ale as a preservative in the 15th and 16th centuries, bringing the new label of “beer” to the concoction.

[2] See Fireflies, Honey, and Silk (2009) by Gilbert Waldbauer, pg. 6-7.

[3] The scarab beetle was considered sacred by ancient Egyptians due to the similarity in its dung ball rolling to the way the god Khepera rolled the sun across the sky. The beetle also represented the soul leaving mummified bodies similar to the way adult beetles emerged from the dirt after growing from the larval stage. See Fireflies, Honey, and Silk (2009) by Gilbert Waldbauer, pg. 94-95.

[4] Curious Facts in the History of Insects; Including Spiders and Scorpions (1865) by Frank Cowan. See page 17-18 for discussion of Viennese rhyme.

[5] “Bad luck will attend anyone who kills a ladybird” (pg. 160) Ecyclopaedia of Superstitions (1891) by Edwin E. Radford.

[6] See Fireflies, Honey, and Silk (2009) by Gilbert Waldbauer, pg. 157-58.

[7] Named for their appearance alongside potato crops, Colorado potato beetles eat the leaves of plants and are considered a garden pest.

[8] Tubercle: A small, knobby, nodule or protuberance on a plant or animal. (Merriam-Webster)

[9] Orig. spelling.

[10] Quiescent: Tranquil, inactive. (Merriam-Webster)

[11] Depredate: To plunder, ravage. (Merriam-Webster)

[12] Possibly referring to Reverand James Hurdis (1763-1801), a British poet and professor of poetry at Oxford University. See his poetry here.

[13] “To the Burnie Bee” by English poet Robert Southey in Joan of Arc, Ballads, Lyrics, and Minor Poems (1857), page 390.

[14] Impennous: Wanting wings. (Emily Dickinson Lexicon). Here, “pennous” most likely refers to the insects wings.

Contexts

The Author: Although little is known about Marie Estelle, she also published two other articles about insects in The Little Corporal, “The Katydids” in Volume 11, issue 5 (November 1870) and “The Praying Mantis” in Volume 12, issue 1 (January 1871). (Philadelphia Area Archives Research Portal).

The Little Corporal: On her website titled “Nineteenth Century Children and What They Read“, Pat Pflieger writes of this periodical: “Founded at the end of the Civil War, The Little Corporal featured a military metaphor and a mascot dressed in a Zouave’s uniform. It devoted itself to “fighting against wrong, and for the good, the true, and the beautiful.” Not especially famous for the quality of its stories or illustrations, the Corporal offered readers pieces emphasizing morality, and a certain coziness.” (The Little Corporal). Pflieger also notes that the Chicago Tribune reported in 1866 President Andrew Johnson had subscribed to the periodical. The publication was eventually absorbed by another popular juvenile periodical of the time, St. Nicholas.