The Cholera-King

By H. W. Ellsworth

Annotations by Kristina Bowers

He cometh! a conqueror proud and strong,

At the head of a mighty band

Of the countless dead, as he passed along,

That he slew with his red right-hand[1];

And over the mountain, or down the vale,

As his shadowy train sweeps on,

There stealeth a lengthened note of wail

For the loved and early gone!

He cometh! the sparkling eye grown dim,

And heavily draws the breath

Of the trembler who whispers low of HIM,

And his standard-bearer, DEATH!

He striketh the rich man down from power,

And wasteth the student pale;

Nor ’scapes him the maid in her latticed bower[2],

Nor the chieftain armed in mail.

He cometh! through ranks of steel-clad men,

To the heart of the warrior-band;

Ye may count where his conquering step hath been,

By the spear in each nerveless hand.

Wild shouteth he where, on the battle-plain,

By the dead are the living hid,

As he buildeth up, from the foeman slain,

His skeleton-pyramid!

There stealeth, ’neath yonder turret’s height.

A lover with song and lute,

Nor knoweth the lips of his lady bright

Are pale, and her sweet voice mute:

For he dreameth not, when no star is dim,

Nor cloud in the summer sky,

That she who from childhood lovéd him

Hath laid her down to die!

She watcheth—a fond young mother dear,

While her heart beats high with pride,

How she best to the good of life may rear

The first-born by her side;

With a fervent prayer, and a love-kiss warm,

She hath sunk to a dreamless rest,

Unconscious all of the death-cold form

That she claspeth to her breast!

Sail ho! for the ship that tireless flies,

While the mad waves leap around,

As she spreadeth her wings for the native skies

Of the wanderers homeward bound:

Away! through the trackless waters blue!

Yet, ere[3] half her course is done,

From the wasted ranks of her merry crew

There standeth only one!

All hushed is the city’s busy throng,

Where it sleeps in the fold of death,

As the desert o’er which hath passed along

The pestilent simoom’s[4] breath!

All hushed—save the chilled and stifling heart

Of some trembling passer-by,

As he looketh askance on the dead man’s cart,

Where it waiteth the next to die!

The fire hath died from the cottage-hearth;

The plough on the unturned plain

Stands still, while unreaped to the mother earth

Down droppeth the golden grain!

Of the loving and loved that gathered there,

Each living thing hath gone,

Save the dog that howls to the midnight air,

By the side of yon cold white stone!

He cometh! He cometh! No human power

From his advent[5] dread can flee;

Nor knoweth one human heart the hour

When the Tyrant his guest shall be:

Or whether at flush of they rosy dawn,

Or at noon-tide’s fervent heat,

Or at night, when, with robe of darkness on,

He treadeth with stealthy feet!

He cometh! A conqueror proud and strong,

At the head of a mighty band

Of the countless dead, as he passed along,

That he slew with his right-hand:

And over the mountain, or down the vale,

As his shadowy train sweeps on,

There stealeth a lengthened note of wail

For the loved and early gone!

Ellsworth, H. W. “The Cholera—King.” The Knickerbocker; or New York Monthly Magazine. 39, no. 2 (Feb 1852): 128.

[1] “Red right-hand” most likely refers to the red right hand of God in John Milton’s Paradise Lost (2.174). In the poem, a demon is speculating God’s ability to plague the demons in heaven if they continue to war.

[2] Bower: A lady’s private apartment in a medieval castle. (Merriam-Webster)

[3] Ere: Before, earlier than. (Merriam-Webster)

[4] Simoom: A hot, dry, violent dust storm or wind occuring in Asian and African deserts. (Merriam-Webster)

[5] Advent: Coming into being or use. (Merriam-Webster)

Contexts

“The Cholera-King” was originally published in The Knickerbocker magazine in 1852.[1] This poem was later published in Early Indiana Trials and Sketches: Reminiscences (1858) by Oliver Hampton Smith and The Poets and Poetry of the West: With Biographical and Critical Notices (1860) by William T. Coggeshall. Biographical information about Ellsworth can also be found in Coggeshall’s book.

Cholera, a disease that causes excessive diarrhea and loss of water and electrolytes from the body, has spread through global pandemics seven times in recorded human history. It first reached the U.S. during the second global pandemic in the 1830s, starting in New York and Philadelphia. The third pandemic, lasting from 1852-1859, however, was the deadliest worldwide. [1]

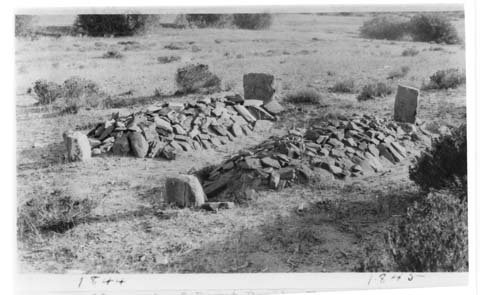

During the third pandemic, cholera spread from the east coast to the Midwest due to the Gold Rush and was carried along routes like the Oregon Trail. Rosenberg writes in the book The Cholera Years: The United States in 1832, 1849, and 1866, “Gold-seekers carried the disease with them across a continent…The route westward was marked with wooden crosses and stone cairns, the crosses often bearing only a name and the world ‘cholera’…It was in the infant cities of the West, with no adequate water supply, primitive sanitation, and crowded with a transient population, that the disease was most severe” (1987, 115).

Resources for Further Study

- Ellsworth’s diplomatic papers generated during his time as U.S. Minister to Sweden and Norway are available at the Library of Congress.

- Rosenberg, Charles E. 1987. The Cholera Years: The United States in 1832, 1849, and 1866. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Contemporary Connections

According to History.com, during the second global cholera pandemic, upon spreading to Great Britain, “Britain enacted several actions to help curb the spread of the disease, including implementing quarantines and establishing local boards of health. But the public became gripped with widespread fear of the disease and distrust of authority figures, most of all doctors. Unbalanced press reporting led people to think that more victims died in the hospital than their homes, and the public began to believe that victims taken to hospitals were killed by doctors for anatomical dissection, an outcome they referred to as “Burking.” This fear resulted in several “cholera riots” in Liverpool.” [1] Although not contagious in the same way, the 1918 Flu Pandemic and current 2020 COVID-19 pandemic have seen similar distrust in science and doctors along with protests against public health measures to curb the spread of these diseases including mask wearing, quarantines, and social distancing [2,3,4]. See this NY Times article “The Mask Slackers of 1918” for more information about anti-mask sentiment during this pandemic.