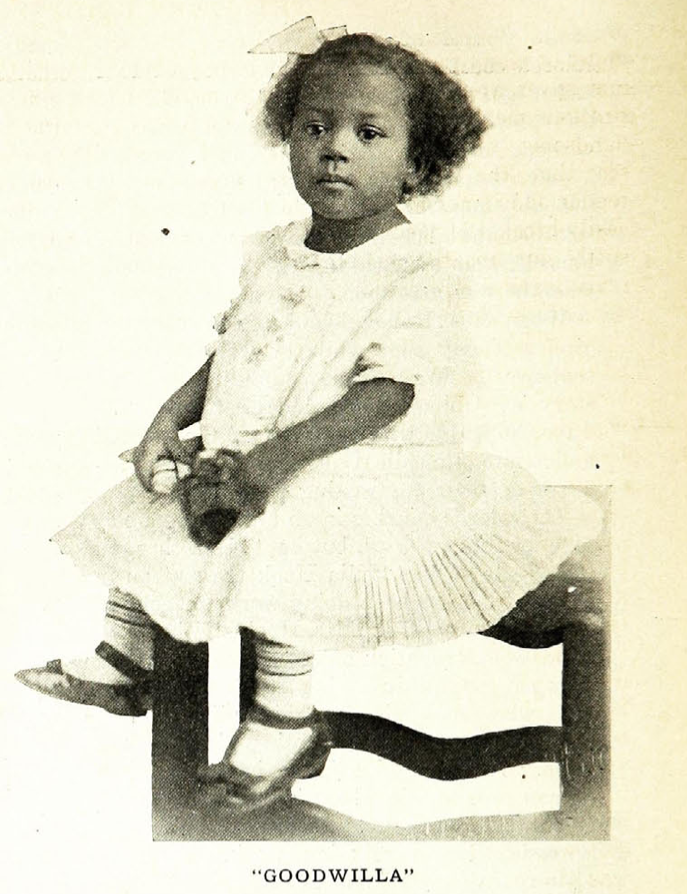

The Fairy Goodwilla

By Minnibelle Jones, age 10

Annotations by Rene Marzuk

In the good old days when the kind spirits knew that people trusted them, they allowed them selves to be seen, but now there are just a few human beings left who ever remember or believe that a fairy ever existed, or rather does exist. For, dear children, no matter how much the older folks tell you that there are no fairies, do not believe them. I am going to tell you now of a clear, good fairy, Goodwilla, who has been under the power of a wicked enchanter called Grafter, for many years.

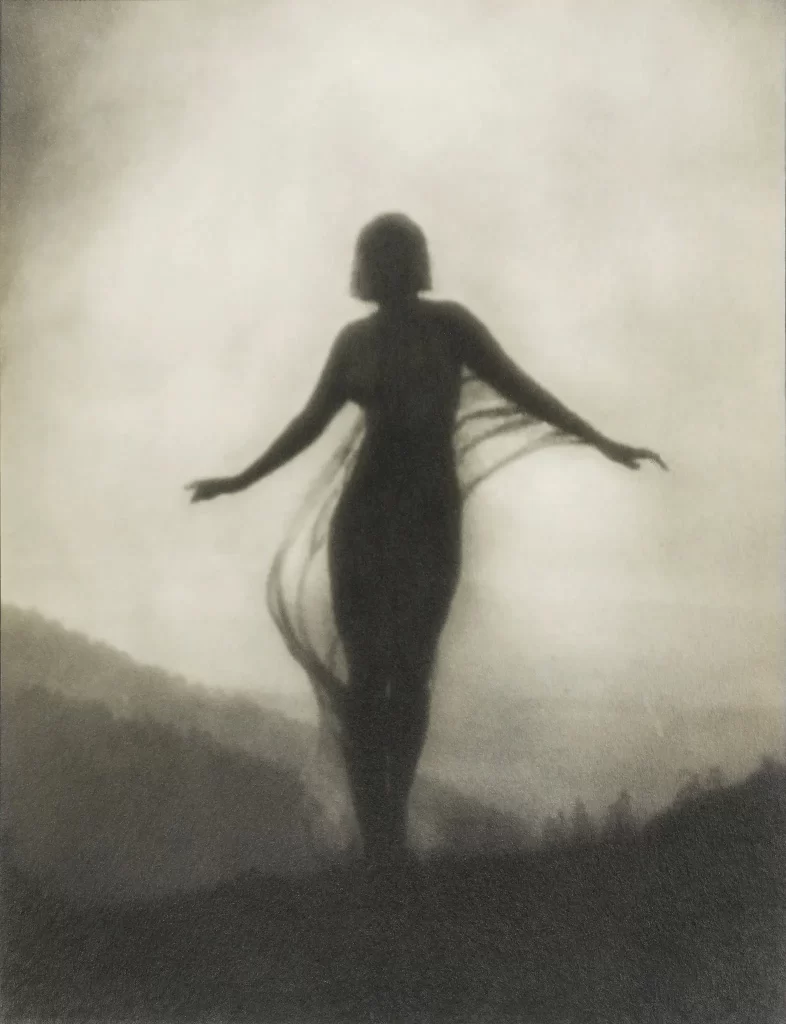

Goodwilla was once a very happy and contented little fairy. She was a very beautiful fairy; she had a soft brown face and deep brown eyes and slim brown hands and the dearest brown hair that wouldn’t stay “put,” that you ever saw. She lived in a beautiful wood consisting of fir trees. Her house was made of the finest and whitest drifted snow and was furnished with kind thoughts of children, good words of older people and everything which is beautiful and pleasant. She was always dressed in a white robe with a crown of holly leaves on her head.[1] In her hand she carried a long magic icicle, and whatever she touched with this became very lovely to look upon. Snowdrops always sprang up wherever she stepped, and her dress sparkled with many small stars.

The children loved Goodwilla, and she always welcomed them to her beautiful home where she told them of Knights and Ladies, Kings and Queens, Witches and Ogres and Enchanters. She never told them anything to frighten them and the children were always glad to listen. You must not think that Goodwilla always remained at home and told the children stories, for she was a very busy little fairy. She visited sick rooms where little boys or girls were suffering and laid her cool brown hands on their heads, whispering beautiful words to them. She touched the different articles in the room with her magic icicle and caused them to become lovely. Wherever she stepped her beautiful snowdrops were scattered. At other times she went to homes where the father and mother were unhappy and cross. She was invisible to them, but she touched them without their knowing it and they instantly became kind and cheerful. Other days she spent at home separating the good deeds which she had piled before her, from the bad deeds. So you see with all of these things to do Goodwilla was very busy.

Now, there was an old enchanter who lived in a neighboring wood. He was very wealthy, but people feared him, although they visited him a great deal. His house was set in the midst of many trees, all of which bore golden and silver apples.[2] The house was made of precious metal and the inside was seemingly handsome. But looking closely one could see that the beautiful chairs were very tender and if not handled rightly they would easily break. Music was always being played softly by unseen musicians, but one who truly loved music could hear discords which spoiled the beauty of all. In fact, every thing in his palace, although seemingly beautiful, if examined closely, was very wrong. Grafter, which was the enchanter’s name, spent all of his time in instructing men how to be prosperous and receive all that they could for nothing. He did not pay much attention to the children, although once in a while a few listened to his evil words. He was always very busy, but somehow he did not at all times get the results he expected. He scratched his head and thought and thought. Finally, one day he cried, “Ah, I have it, there is an insignificant little fairy called Goodwilla who is meddling in my affairs, I’ll wager. Let me see how best I can overcome her.” The old fellow who could change his appearance at will, now became a handsome young enchanter and looked so fine that it would be almost impossible for the fairy herself to resist him. He made his way to her abode and asked for admittance to her house. She gladly bade him enter, for, although she knew him, she thought she could persuade him to forego his evil ways and win men by fair means.

Now something strange happened. Every chair that Grafter attempted to take became invisible when he started to seat himself and he found nothing but empty air. After this had happened for a long while, he became so angry that he forgot the part he was trying to play and acted very badly indeed. He stormed at poor Goodwilla as if she had been the cause of good deeds and kind words to vanish at his touch. “You, Madam,” said he, “are the cause of this, and I know now why I cannot be successful in my work. You fill the children’s heads full of nonsense and when I have almost persuaded the fathers to do something which will benefit them as well as their children, these brats come with their prattle and undo all that I have done. Now I have stood it long enough. I shall give you three trials, and if you do not conquer, you shall be under my power for seven hundred years.”

The Good Fairy listened and felt very grieved, but she knew that Grafter was stronger than she, as minds of men turned more to his commanding way than they did to hers. Nevertheless she determined to do her best and said, “Very well, Grafter, I shall do as you wish and if I do not succeed I am in your hands, but later everything will be all right and I shall rule over you.” Grafter, who had not expected this, now be came alarmed and thought by soft words he could perhaps coax her to do his way, but Goodwilla was strong and would not listen to his cajoling and flattering. “Then, Madam,” he said, “I shall force you to perform these tasks or be my slave:

“First, you must cause all of the people in the world to help and give to others for the sake of giving and not for what they shall receive in return.

“Secondly, you must cause all of the rich to help the poor instead of taking from them to swell their already fat pocketbooks, and thirdly, you must cause men and women to really love for love’s sake and not because of worldly reasons.”

The poor little fairy sighed deeply, for she knew that she could not perform these tasks in the three days that Grafter had allowed her. She talked to the children, but they were being dazzled by Grafter since he had become so handsome. Goodwilla continued to work though, and had just commenced to open men’s eyes to Grafter as he really was, when the three days expired.

She was immediately whisked off by the wicked old fellow, who chuckled with glee. He did not know that there were many people in whose hearts a seed had been planted (which would grow) by this good little fairy and that she herself had a plan for helping all when she was released. Grafter, after having locked her up, departed on his way rejoicing. He has been prosperous for a long, long time, but the seven hundred years are almost up now, and soon Goodwilla will come forth stronger and more beautiful than ever with the children as her soldiers.

JONES, MINIBELLE. “THE FAIRY GOOD WILLA.” THE CRISIS, VOL. 8, NO. 6 (OCTOBER 1914): 294-96.

[1] The symbolism of holly plants and holly leaves reaches back to antiquity. Druids thought the hollies were sacred and, according to some legends, these plants were a refuge for faeries and nature spirits during winter. In the Christian tradition, the holly is associated with Christ’s crown of thorns.

[2] Apples have had a long life in mythology. Greek and Teutonic myths feature golden apples.

Contexts

Starting in 1912, the October issues of The Crisis, the official magazine of the NAACP, were dedicated to children. A typical edition of these children’s numbers would contain a special editorial piece and two or three literary works specifically for children, while still including the serious pieces about contemporary issues with a focus on race that The Crisis was known for. These October numbers were sprinkled with children’s photographs sent in by the readers.

In his first editorial for the Children’s number in 1912, W. E. B. Du Bois wrote that “there is a sense in which all numbers and all words of a magazine of ideas myst point to the child—to that vast immortality and wide sweep and infinite possibility which the child represents.”

The success of The Crisis’ children’s number led to the standalone The Brownies’ Book, a monthly magazine for African American children that circulated from January 1920 to December 1921 under the editorship of Du Bois, Augustus Granville Dill, and Jessie Fauset.

Resources for Further Study

- A brief history of fairies, courtesy of the World History Encyclopedia collective.

- An article on fairies‘ folklore scholarship, with copious references and suggestions for further reading.

Contemporary Connections

Did you know that June 24th is International Fairy Day?