The Haunted Oak[1]

By Paul Laurence Dunbar

Annotations by Rene Marzuk

Pray, why are you so bare, so bare,

O bough of the old oak tree?

And why, when I go through the shade you throw

Runs a shudder over me?

My leaves were as green as the best, I trow,

And the sap ran free in my veins,

But I saw in the moonlight dim and weird,

A guiltless victim's pains.

I bent me down to hear his sigh,

And I shook with his gurgling moan,

And I trembled sore when they rode away,

And left him here alone.

They'd charged him with the old, old crime,[2]

And set him fast in jail;

O why does the dog howl all night long?

And why does the night wind wail?

He prayed his prayer, and he swore his oath,

And he raised his hands to the sky;

But the beat of hoofs smote on his ear,

And the steady tread drew nigh.

Who is it rides by night, by night,

Over the moonlit road?

What is the spur that keeps the pace?

What is the galling goad?

And now they beat at the prison door,

“Ho, keeper, do not stay!

We are friends of him whom you hold within,

And we fain would take him away

From those who ride fast on our heels,

With mind to do him wrong;

They have no care for his innocence,

And the rope they bear is strong.”

They have fooled the jailer with lying words,

They have fooled the man with lies;

The bolts unbar, the locks are drawn,

And the great door open flies.

And now they have taken him from the jail,

And hard and fast they ride;

And the leader laughs low down in his throat,

As they halt my trunk beside.

O, the judge he wore a mask of black,

And the doctor one of white,

And the minister, with his oldest son,

Was curiously bedight.

O foolish man, why weep you now?

’Tis but a little space,

And the time will come when these shall dread

The memory of your face.

I feel the rope against my bark,

And the weight of him in my grain;

I feel in the throe of his final woe,

The touch of my own last pain.

And never more shall leaves come forth

On a bough that bears the ban;

I am burned with dread, I am dried and dead,

From the curse of a guiltless man.

And ever the judge rides by, rides by,

And goes to hunt the deer,

And ever another rides his soul,

In the guise of a mortal fear.

And ever the man, he rides me hard,

And never a night stays he;

For I feel his curse as a haunted bough,

On the trunk of a haunted tree.

DUNBAR, PAUL LAURENCE. “THE HAUNTED OAK,” IN THE DUNBAR SPEAKER AND ENTERTAINER, ED. ALICE MOORE DUNBAR-NELSON, 91-93. NAPERVILLE, ILL: J. L. NICHOLS & CO., 1920.

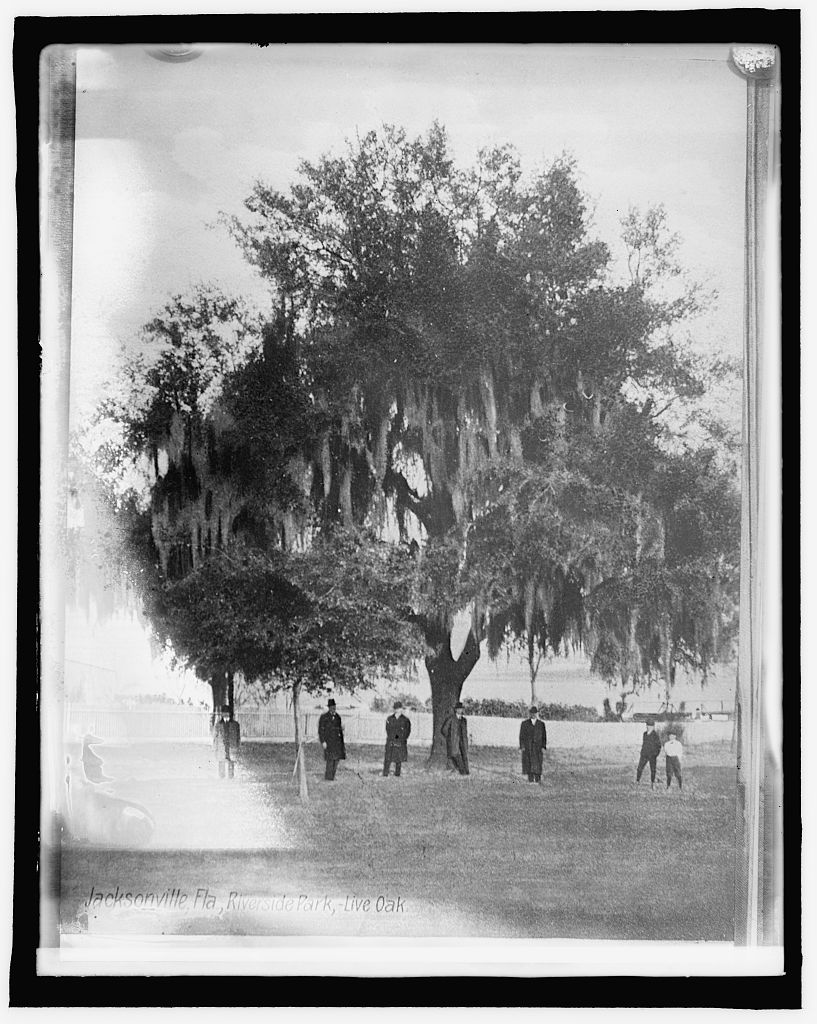

[1] According to Dunbar’s friend Edward F. Arnold, Dunbar wrote “The Haunted Oak” after hearing the story of a lynching that took place in Alabama many years before. In Arnold’s retelling, “the “night riders” took him [the victim, who had been wrongly accused of rape] from jail and strung him up on a limb of a giant oak that stood by the side of the road. In a few weeks thereafter the leaves on this limb turned yellow and dropped off, and the bough itself gradually withered and died while the other branches of the tree grew and flourished. For years in that section this tree was known as the “haunted oak.”

[2] Based on Edward F. Arnold’s account, the poem’s reference to “the old, old-crime” would be rape. See above.

Contexts

“The Haunted Oak” appeared previously in Dunbar’s 1903 collection Lyrics of Love and Laughter. It was also included in The Complete Poems of Paul Laurence Dunbar (1913).

The Dunbar Speaker and Entertainer‘s dedication reads: “To the children of the race which is herein celebrated, this book is dedicated, that they may read and learn about their own people.” In the foreword, Leslie Pinckney Hill, an African American educator, writer, and community leader who graduated from Harvard University in 1903, criticizes the one-sidedness of prevailing reading courses: “In vain may you search their pages—those pages upon which all our reading has been founded—for anything other than a patronizing view of that vast, brooding world of colored folk—yellow, black and brown—which comprises by far the largest portion of the human family.” Hill further writes that Alice Dunbar-Nelson’s book seeks to prove “that the white man has no fine quality, either by heart or mind, which is not shared by his black brother.”

Think of reading this poem out loud. Elocution (or public speaking) was a highly valued and widely taught skill in nineteenth-century America. In her introduction to the Dunbar Speaker, Alice Dunbar-Nelson offers some advice: “Before you begin to learn anything to recite, first read it over and find out if it fires you with enthusiasm. If it does, make it a part of yourself, put yourself in the place of the speaker whose words you are memorizing, get on fire with the thought, the sentiment, the emotion-then throw yourself into it in your endeavor to make others feel as you feel, see as you see, understand what you understand. Lose yourself, free yourself from physical consciousness, forget that those in front of you are a part of an audience, think of them as some persons whom you must make understand what is thrilling you–and you will be a great speaker.”

Definitions from Oxford English Dictionary:

bedight: To equip, furnish, apparel, array, bedeck.

fain: To be delighted or glad, rejoice.

galling: Chafing, irritating or harassing physically. Irritating, offensive to the mind or spirit.

ho: An exclamation to attract attention.

nigh: Denoting approach to a place, thing, or person.

trow: To trust, have confidence in, believe (a person or thing).

Resources for Further Study

- Lynching in America is an interactive website structured around Equal Justice Initiative (EJI)’s comprehensive report Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror.

- In 1955, 14-year-old Emmett Till was lynched in Mississippi after being accused of flirting with a white woman. The aftermath of his murder ignited the emerging U.S. civil rights movement.

- A selected bibliography of Paul Laurence Dunbar’s works, courtesy of Wright State University’s Special Collections & Archives Department.

- Paul Laurence Dunbar also deals with the topic of lynching in his 1904 short story “The Lynching of Jube Benson.”

Contemporary Connections

In a moving personal essay, American poet Glenis Redmond explores how the history of lynching complicates her relationship with the Southern landscape: “The legacy of lynching is woven into the fabric of America. Used as a tool of fear and a widespread form of control after blacks gained freedom from slavery, it has cast its long shadow across the country. Trees, though benign in themselves, stand at the center of this history, and they bear that imprint.”