The Indian Girl

By Zitkála-Šá (Yankton Nakota)[1]

Annotations by Jessica Cory

I was a wild little girl of seven. Loosely clad in a slip of brown buckskin, and light – footed with a pair of soft moccasins on my feet, I was as free as the wind that blew my hair, and no less spirited than a bounding deer. These were my mother‘s pride, — my wild freedom and overflowing spirits. She taught me no fear save that of intruding myself upon others.

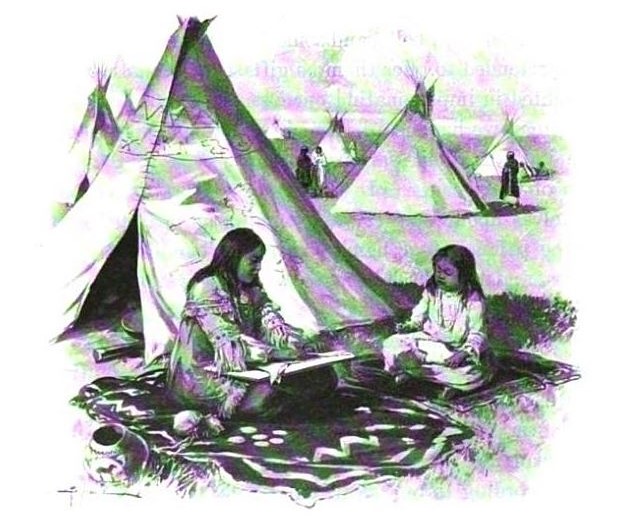

In the early morning our simple breakfast was spread upon the grass west of our tepee. At the farthest point of the shade my mother sat beside her fire, toasting a savory piece of dried meat. Near her I sat upon my feet, eating my dried meat with unleavened bread, and drinking strong black coffee.

Soon after breakfast mother sometimes began her bead work. On a bright, clear day she pulled out the wooden pegs that pinned the skirt of our wigwam to the ground, and rolled up the canvas on its frame of slender poles. Then the cool morning breezes swept freely through our dwelling, now and then wafting the perfume of sweet grasses from newly burnt prairie.

Untying the long, tasseled strings that bound a small brown buckskin bag, my mother spread upon a mat beside 5 her bunches of colored beads, just as an artist arranges the paints upon his palette. On a lapboard she smoothed out a double sheet of soft white buckskin; and drawing ‘from a beaded case that hung on the left of her wide belt a long, narrow blade, she trimmed the buckskin into shape. Often she worked upon moccasins for her small daughter. Then I became intensely interested in her designing. With a proud, beaming face I watched her work. In imagination I saw myself walking in a new pair of snugly fitting moccasins. I felt the eyes of my playmates upon the pretty red beads decorating my feet.

Close beside my mother I sat on a rug, with a scrap of buckskin in one hand and an awl in the other. This was the beginning of my practical observation lessons in the art of beadwork. It took many trials before I learned how to knot my sinew thread on the point of my finger, as I saw her do. Then the next difficulty was in keeping my thread stiffly twisted, so that I could easily string my beads upon it. My mother required of me original designs for my lessons in beading. At first I frequently insnared many a sunny hour into working a long design. Soon I learned from self – inflicted punishment to refrain from drawing complex patterns, for I had to finish whatever I began.

After some experience I usually drew easy and simple crosses and squares. My original designs were not always symmetrical nor sufficiently characteristic, two faults with which my mother had little patience. The quietness of her oversight made me feel responsible and dependents upon my own judgment. She treated me as a dignified little individual as long as I was on my good behavior; and how humiliated I was when some boldness of mine drew forth a rebuke from her!

Always after these confining lessons I was wild with surplus spirits, and found joyous relief in running loose in the open again. Many a summer afternoon a party of four or five of my playmates roamed over the hills o with me. I remember well how we used to exchange our necklaces, beaded belts, and sometimes even our moccasins. We pretended to offer them as gifts to one another. We delighted in impersonating our own mothers. We talked of things we had heard them say in their conversations. We imitated their various manners, even to the inflection of their voices. In the lap of the prairie we seated ourselves upon our feet; and leaning our painted cheeks in the palms of our hands, we rested our elbows on our knees, and bent forward as old women were accustomed to do.

While one was telling of some heroic deed recently done by a near relative, the rest of us listened attentively, and exclaimed in undertones, “Han! han!”(Yes! yes! ) whenever the speaker paused for breath, or sometimes for our sympathy. As the discourse became more thrilling, according to our ideas, we raised our voices in these interjections.

No matter how exciting a tale we might be rehearsing, the mere shifting of a cloud shadow in the landscape near by was sufficient to change our impulses; and soon we were all chasing the great shadows that played among the hills. We shouted and whooped in the chase; laughing and calling to one another, we were like little sportive nymphs on that Dakota sea of rolling green.

One summer afternoon my mother left me alone in our wigwam, while she went across the way to my aunt’s dwelling.

I did not much like to stay alone in our tepee, for I feared a tall, broad – shouldered crazy man, some forty years old, who walked among the hills. Wiyaka – Napbina (Wearer of a Feather Necklace) was harmless, and when ever he came into a wigwam he was driven there by extreme hunger. In one tawny arm he used to carry a heavy bunch of wild sunflowers that he gathered in his aimless ramblings. His black hair was matted by the winds and scorched into a dry red by the constant summer sun. As he took great strides, placing one brown bare foot directly in front of the other, he swung his long lean arm to and fro.

I felt so sorry for the man in his misfortune that I prayed to the Great Spirit to restore him, but though I pitied him at a distance, I was still afraid of him when he appeared near our wigwam.

Thus, when my mother left me by myself that after noon, I sat in a fearful mood within our tepee. I recalled all I had ever heard about Wiyaka – Napbina; and I tried to assure myself that though he might pass near by, he would not come to our wigwam because there was no little girl around our grounds.

Just then, from without, a hand lifted the canvas covering of the entrance; the shadow of a man fell within the wigwam, and a roughly – moccasined foot was planted inside.

For a moment I did not dare to breathe or stir, for I thought that it could be no other than Wiyaka – Napbina. The next instant I sighed aloud in relief. It was an old grandfather who had often told me Iktomi legends.

“Where is your mother, my little grandchild?“ were his first words.

“My mother is soon coming back from my aunt’s tepee, “I replied.

“Then I shall wait a while for her return, “he said, crossing his feet and seating himself upon a mat.

At once I began to play the part of a generous hostess. I turned to my mother’s coffeepot.

Lifting the lid I found nothing but coffee grounds in the bottom. I set the pot on a heap of cold ashes in the center of the wigwam, and filled it half full of warm Missouri River water. During this performance I felt conscious of being watched. Then breaking off a small piece of our unleavened bread, I placed it in a bowl. Turning soon to the coffeepot, which would not have boiled on a dead fire had I waited forever, I poured out a cup of worse than muddy warm water. Carrying the bowl in one hand and the cup in the other, I handed the light luncheon to the old warrior. I offered them to him with the air of bestowing generous hospitality.

“How! how!“ he said, and placed the dishes on the ground in front of his crossed feet. He nibbled at the bread and sipped from the cup. I sat back against a pole watching him. I was proud to have succeeded so well in serving refreshments to a guest. Before the old warrior 5 had finished eating, my mother entered. Immediately she wondered where I had found coffee, for she knew I had never made any and that she had left the coffeepot empty. Answering the question in my mother‘s eyes, the warrior remarked, “My granddaughter made coffee on a heap of dead ashes, and served me the moment I came.”

They both laughed, and mother said, “Wait a little longer, and I will build a fire.” She meant to make some real coffee. But neither she nor the warrior, whom the law of our custom had compelled to partake of my insipid hospitality, said anything to embarrass me. They treated my best judgment, poor as it was, with the utmost respect. It was not till long years afterward that I learned how ridiculous a thing I had done. [1]

Zitkala-Ša. “the indian girl.” in the jones fifth reader, edited by L.m. Jones, 441-447. Boston: Ginn & Company, 1903.

[1] The Yankton Nakota are also sometimes called the Yankton Sioux. Located in South Dakota, “the reservation is the homeland of the Ihanktonwan or Yankton and the Ihanktowanna or Yanktonai who refer to themselves as Nakota.” Some sources have noted Zitkála-Šá as being Yankton Dakota. Legends of America explains the differences in Dakota, Lakota, and Nakota, as well the problematic term “Sioux.”

Contexts

This piece, published in 1903, appears to be a cross-written version of Zitkála-Šá’s “Impressions of An Indian Childhood” which was originally published in 1901 in the Atlantic Monthly. The piece also begins her 1921 book American Indian Stories. American Indian Stories is largely autobiographical and highlights the stark contrast between Zitkála-Šá’s childhood on the reservation, as the piece above shows, and her experience at White’s Indiana Manual Labor Institute, a boarding school for Native children that was operated by Quaker missionaries.

Resources for Further Study

- This document provides a bit more information on Quaker-run boarding schools and specifically mentions Zitkála-Šá’s American Indian Stories.

- To learn more about the Yankton Reservation, please see the transcribed treaty that the U.S. government entered into with the Yankton tribe in 1858. This short article by the National Parks Service explains the pressure the Yankton were under in signing the treaty and the National Archives gives additional background on the 1858 treaty..

Contemporary Connections

Concerned about waste management facilities encroaching on and polluting the reservation, the Yankton tribe sued the state of South Dakota twice, once in 1995 and again in 1997. In both cases, the courts rejected the Tribe’s claims.