The Seedling

By Paul Laurence Dunbar

Annotations by Rene Marzuk

As a quiet little seedling,

Lay within its darksome bed,

To itself it fell a-talking,[1]

And this is what it said:

"I am not so very robust,

But I'll do the best I can,"

And the seedling from that moment,

Its work of life began.

So it pushed a little leaflet,

Up into the light of day,

To examine the surroundings,

And show the rest the way.

The leaflet liked the prospect,

So it called its brother, Stem,

Then two other leaflets heard it.

And quickly followed them.

To be sure, the haste and hurry,

Made the seedling sweat and pant;

But almost before it knew it,

It found itself a plant.

The sunshine poured upon it,

And the clouds, they gave a shower;

And the little plant kept growing,

Till it found itself a flower.

Little folks, be like the seedling,

Always do the best you can,

Every child must share life's labor,

Just as well as every man.

And the sun and showers will help you,

Through the lonesome, struggling hours,

Till you raise to light and beauty,

Virtue's fair, unfading flowers.

DUNBAR, PAUL LAURENCE. “THE SEEDLING,” IN THE DUNBAR SPEAKER AND ENTERTAINER, ED. ALICE MOORE DUNBAR-NELSON, 19-20. NAPERVILLE, ILL: J. L. NICHOLS & CO., 1920.

[1] A-prefixing is a distinctive feature of Southern American White English, particularly Appalachian English. Scholars argue that it may have originated among settlers from southern England.

Contexts

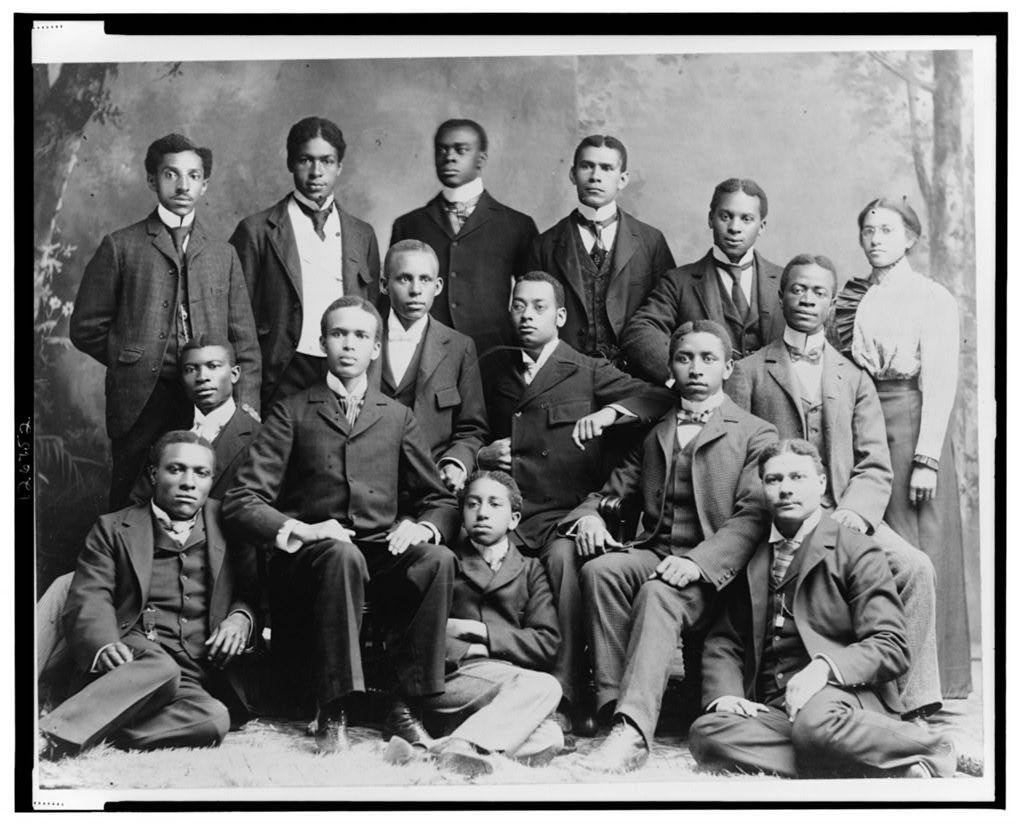

The Dunbar Speaker and Entertainer‘s dedication reads: “To the children of the race which is herein celebrated, this book is dedicated, that they may read and learn about their own people.” In the foreword, Leslie Pinckney Hill, an African American educator, writer, and community leader who graduated from Harvard University in 1903, criticizes the one-sidedness of prevailing reading courses: “In vain may you search their pages—those pages upon which all our reading has been founded—for anything other than a patronizing view of that vast, brooding world of colored folk—yellow, black and brown—which comprises by far the largest portion of the human family.” Hill further writes that Alice Dunbar-Nelson’s book seeks to prove “that the white man has no fine quality, either by heart or mind, which is not shared by his black brother.”

Think of reading this poem out loud. Elocution (or public speaking) was a highly valued and widely taught skill in nineteenth-century America. In her introduction to the Dunbar Speaker, Alice Dunbar-Nelson offers some advice: “Before you begin to learn anything to recite, first read it over and find out if it fires you with enthusiasm. If it does, make it a part of yourself, put yourself in the place of the speaker whose words you are memorizing, get on fire with the thought, the sentiment, the emotion-then throw yourself into it in your endeavor to make others feel as you feel, see as you see, understand what you understand. Lose yourself, free yourself from physical consciousness, forget that those in front of you are a part of an audience, think of them as some persons whom you must make understand what is thrilling you–and you will be a great speaker.”

Resources for Further Study

- The Library of Congress offers a set of primary sources that illustrate the reality of American children’s lives at the beginning of the twentieth century.

- In her book Racial Innocence: Performing American Childhood from Slavery to Civil Rights, Robin Bernstein illustrates how the American idea of childhood innocence became racialized and excluded black children.