The World We Live On

By Elizabeth Cabot Cary Agassiz

Annotations by Josh Benjamin

To the young folks, — to all the young folks, — to my especial friends I among them, and to those whom I shall never know except as a distant crowd of bright and happy boys and girls whom I like to imagine reading this Magazine, I dedicate the following pages. Sometimes, perhaps, when they have finished the stories, they will enjoy turning to my more serious chapters.

There are few among you, I fancy, who have not grown up under the impression that the world we live upon has been always, so far as its general features are concerned, much what it is now. You know that forests have been cleared, that countries have been marked out according to certain boundaries, that cities have been built, and that countless changes have taken place upon the earth’s surface; but these changes are all connected with the history of man. Your school-books tell you little or nothing of the extraordinary events which preceded by ages the very existence of mankind, and prepared the world to be our home. Your map shows you the United States as they exist to-day, and your lesson in geography gives you the name and boundaries, the rivers, mountains, and lakes, the cities and towns, of every State; but while it teaches you so many facts about the State of New York, for instance, it tells you nothing of an ancient sea-shore running through its centre from east to west, the record of a time when America itself was but a long, narrow island, around which the ocean washed.

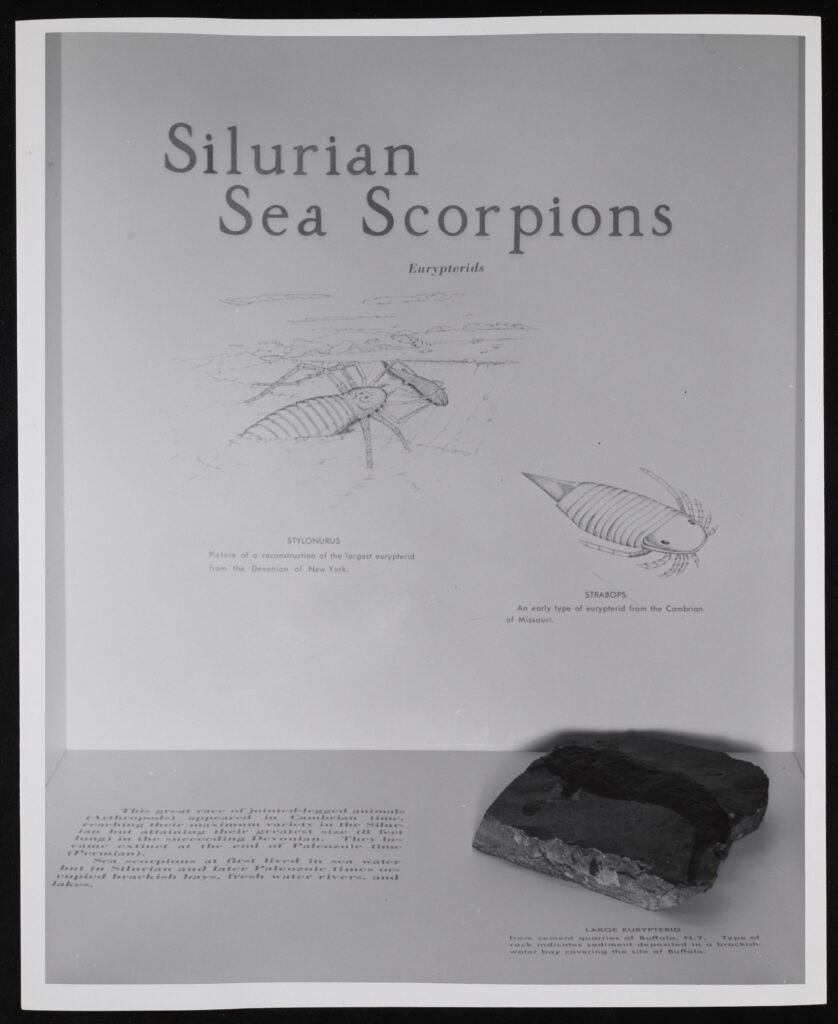

You go, perhaps, to Trenton Falls, and gather there the curious animal remains of which the rocks are full; but as you pick up the fossil shells, or look at the curious old crustacea called trilobites, I doubt whether it occurs to you that you are doing just what you might do at Newport, or Long Branch, or Nahant, namely, walking on a beach, and picking up the animals which lived upon it.

In the very spot from which I write, Ithaca, in the State of New York, lying on a line parallel with the old sea-shore of Trenton, the young people are all familiar with the broken bits of clay, slate, or limestone, to be found at every roadside, filled with shells and remains of marine animals; but I doubt whether they ask themselves how it happens that here, so far from the ocean, sea-shells are so common that the very rocks are crowded with them. Perhaps they wonder how they came there; but, as their school-books tell them nothing about it, they are contented to let it remain a mystery. Indeed, it is not very long since the wiseșt scientific men asked themselves the same question, and could find no answer. Only by very slow degrees have they learned, that, in the process of building the world, sand and mud, sea-shores, lake and river bottoms, have been consolidated, have hardened into rock, petrifying within them the animals living upon their surface, and the plants growing upon their soil. It is not very difficult, when one has the clew to it, to understand how this may happen. An animal, dying, sinks into the sand or mud, as the case may be; his solid parts — such as the hard envelopes we call shells, or the skeleton of a fish — do not decay; if more and more sand or mud is piled above him, and hardens into rock, in the course of time, by the pressure of its own weight, the animal is embalmed there for ages, till for some purpose or other the rock is split, and he is found in his strange tomb.

Of these things I will tell you more in detail hereafter, if you care to listen. Just now I only want to show that our world has assumed its present outline and general character very gradually, and that creation has been a process of growth, not a single complete act.

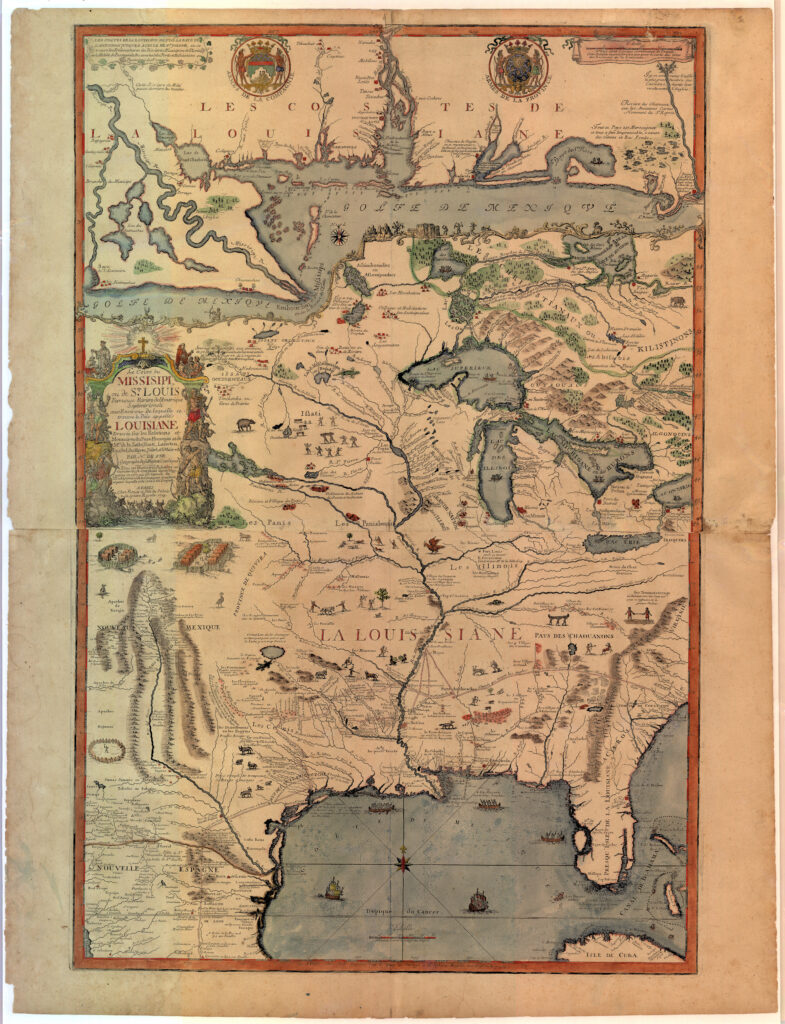

Let us return to our geography lesson. Go a little farther west, and we come to the bank of the Mississippi, and our map shows us the great river flowing from north to south, from Minnesota to Louisiana, till it empties into the Gulf of Mexico, but our geography tells us nothing of a great gulf once occupying almost the whole of what is called the Mississippi Valley, when the States now forming the boundaries of the river had no existence, and all that part of our continent lay open to the ocean. Nor does it say anything of a time when there were neither Rocky Mountains nor Alleghanies, when immense marshes, on which grew forests wholly unlike our forests, filled the central part of the United States. No doubt it speaks of the coal beds in Ohio and Pennsylvania, and explains how coal is formed by the decomposition of plants; but these coal beds have a story of their own to tell, which would interest the dullest mind. They were built up by the slow decay of vast forests, in which the largest trees were of a kind known to us now almost entirely as ferns, rushes, reeds, and the like. It is true that some large representatives of them still exist, but they grow in very different climates from ours, — in the tropical parts of South America, where there are tall and stately tree-ferns, and where some of the palms also resemble the trees of the coal forests.

You may ask how we know all this, if nothing remains of these forests except the coal. We know it because the coal beds are full of stems, leaves, fragments of trunks, fruits, seed-vessels, in all of which the structure is perfectly preserved. The coal, you must remember, was once only mud, the trees falling in swampy ground, soaked with rain, slowly decomposing, and forming a rich loamy soil, as trees do now, if they are left to decay where they lie. My young readers must not suppose, however, that one or twenty such forests would make a coal deposit of much thickness; on the contrary, countless generations of trees must have grown up and perished, before the beds of coal were formed which feed all our fires to-day. As the layers of vegetable soil formed by the decomposition of such successive forests were heaped one upon another, the pressure of the upper ones consolidated those below, and gradually transformed the whole mass from a soft to a hard substance. Here and there, however, a branch, a fallen leaf, a fruit or seed, has been buried in this soil without decaying; and by such remains we are enabled to decipher the character of these old woods.

Then came another process; this mass had to be baked, to give it the character of coal. For reasons which, so far as I understand them myself, I shall try to explain hereafter, the interior of the earth is hotter than its surface. Here and there this internal heat finds an outlet, — comes in contact with what geologists call the crust of our globe, that is, with the solid envelope which forms its surface. This envelope is composed of a great number of materials, — sand, mud, lime, &c.; and these materials are changed into a variety of substances by the action of heat. The effect of this heating process upon the deposits left by the dying forests of which we have been talking was to change them into coal. We shall see hereafter, if you care to know more about it, how the petroleum of which we hear so much nowadays is connected with this same internal furnace, and with the coal beds themselves.

Leaving the Middle States, and going farther south, we read there the same story of change and gradual growth. In the days when the coal forests existed, there was no Florida at all. It has been built on to our continent by coral animals, — strange little workmen, the busiest and most patient architects the world has ever seen, whose history we will study together.

In short, all the countries with the present aspect of which your geography makes you familiar have grown slowly, through innumerable ages, to be what we find them. Europe was once an archipelago of islands in the wide ocean, — a bit of France here, a fraction of Germany there, Russia just showing herself above the waters, neither Alps nor Apennines nor Pyrenees to be seen. There are regions of Central Europe, now far removed from the sea-shores, the soil of which is so filled with remains of marine animals, that you cannot take up a handful of roadside dust without gathering a variety of shells. The mountains of the Jura, in Switzerland, are full of such localities. There is a very romantic gorge running from the base of the Jura, near Montagny, to the village of St. Croix, about half-way up the slope of the range. I well remember wandering through it one summer afternoon with a party of friends, and our amusing ourselves, as we walked along, by breaking off bits from the brittle rocks forming the walls of the precipitous chasm, and examining the shells which fell from them as they crumbled under our touch. Resting afterwards on the mountain terrace above, while we ate our lunch of bread and cheese, and looking across the plain of Switzerland to the Alps, it was difficult to believe that the ocean had ever washed over that fertile land, and had broken against the base of the very range on which we sat.

In the series of chapters I propose to write for “Our Young Folks,” I shall attempt to explain, as far as modern geology teaches it to us, how these changes were brought about; what agents have been at work fashioning this earth on which we live, building it up or wearing it away, heating it in the great furnace of nature, cooling it gradually till a crust was formed upon its surface. We shall see that vapors condensed, and oceans slowly gathered about this world of ours, that gradually land was lifted above the face of the waters, that after a while life stirred on those newly baptized shores, and that at last the earth, so carefully prepared for this end, became inhabited, but not by beings of exactly the same kind as those which live upon it now.

True, there were corals and strange old star-fishes mounted on stems, and spreading their fringed cups like flowers in the water; there were shells endless in number, infinite in variety; there were crustacea, that is, animals resembling our shrimps, crabs, and lobsters; and there were fishes also, — but neither fish nor shrimp nor shell nor star-fish was our familiar acquaintance of to-day. In their general structure they were the same, so that the naturalist recognizes them at once; but that structure was presented under singular, old-fashioned forms, very unlike their representatives now.

All the earliest animals were marine, for the very good reason that in those days the world was wholly ocean and low sea-shore. There was neither forest nor field; no very wide expanses of surface were raised above the water, and the dry land was not yet prepared to receive its myriads of inhabitants. But the beaches were ready; their sands and shallows swarmed with a busy, crowded life; and let me remind you again that, when we split some bit of inland rock, and find it full of shells, broken fragments of crustacea, or star-fish, we do but break in upon one of the little colonies which had their homes upon those primitive shores, lived and died upon them as our animals of the same kind live and die upon our sea-shores to-day.

Nor is it strange that we find small fragments of rock thronged with these remains, while large masses in their immediate neighborhood do not contain any. We see the same thing on our beaches now; many of these animals are naturally gregarious; others are brought together by the fact that in certain very limited localities they find exactly what they need to sustain existence. How often, in looking for sea-anemones, or star-fishes, or crabs, we find them crowded into some little corner they have chosen for their home, while we may hunt for them in vain over all the neighboring space.

Gradually I hope to make you acquainted with some of these early animals, and to show you that not only the earth, but the beings living upon its surface, have been different at successive periods. We must, however, always remember that there has been a connection between the past and present; that the period to which we ourselves belong, and all those preceding it, are chapters of one and the same story, intelligently linked from first to last. We know it but in part; many of the pages are so torn and defaced that it seems impossible to decipher them, and some are wholly missing. And yet, bit by bit, the students of nature are putting the broken record together, and puzzling it out for us.

We will not, however, go back at once to the ancient world and its inhabitants, in our talks about Natural History. What is near and familiar is more readily understood than what is strange and distant; a special fact is more easily explained than a wide, comprehensive view. So I will begin, not with the great features of the world’s history, but with a very small portion of its present surface.

In my next chapter I will tell you something of the peninsula of Florida. We shall see with what silent, quiet patience the ages have added this single outlying State to our continent, and we shall then be better prepared to understand the more general phenomena affecting the outline and character of the whole earth.

Agassiz, Elizabeth CAbot Cary. “The world we live on.” Our Young folks 5, No. 1 (january 1869): 38-41.

Contexts

By the time of this chapter’s appearance, Agassiz had published her own natural history texts and contributed to her husband’s expedition journals and publications. There was widespread interest among white Americans in expeditions to explore, study, and map locations throughout the country; for example, the Folsom-Cook exploration of the upper Yellowstone and the Powell Geographic Expedition along the Green and Colorado rivers set out later in 1869.

Resources for Further Study

- The Folsom-Cook Expedition explored the Yellowstone Park region.

- The Powell Geographic Expedition included the Grand Canyon.

Contemporary Connections

Many of the white, male scientists working during this time, despite the advances in understanding geography, geology, and natural history, still held racist views of human history. Agassiz espoused problematic polygenic theories and Powell furthered ideas of Native American racial inferiority.