What Animals Use for Hands

By Worthington Hooker, MD

Annotations by kathryn t. burt

Though animals do not have hands, they have different parts which they use to do some of the same things that we do with our hands. I will tell you about some of these in this chapter

You see this dog dragging along a rope which he holds in his mouth. He is making his teeth answer in place of hands. Dogs always do this when they carry things. They can not carry them in any other way. You carry a basket along in your hand, but the dog takes it between his teeth, because he has no hand as you have.

I have told you, in another chapter, how the cow and the horse crop the grass. They do it, you know, with their front teeth. They take up almost any kind of food—a potato, an apple—with these teeth. These teeth, then, answer for hands to the cow and horse. Their lips answer also the same purpose in many cases. The horse gathers his oats into his mouth with the lips. The lips are for hands to such animals in another respect. They feel things with their lips just as we do with the tips of our fingers.

My horse once, in cropping some grass, took hold of some that was so stout[1] and so loose in the earth that he pulled it up by the roots. As he ate it the dirt troubled him. He therefore knocked the grass several times against the fence, holding it firmly in his teeth, and thus got the dirt out, just as people do out of a mat when they strike it against any thing. I once knew a horse that would lift a latch or shove a bolt with his front teeth as readily as you would with your hand. He would get out of the barn yard in this way. But this was at length prevented by a very simple contrivance. A piece of iron was fixed in such a manner at the end of the bolt that you could not shove the bolt unless you raised the iron at the same time. Probably this puzzled the horse’s brain. Even if he understood it, he could not manage the two things together. I have heard about a horse that would take hold of a pump-handle with his teeth and pump water into a trough when he wanted to drink. This was in a pasture where there were several horses; and what is very curious, the other horses, when they wanted to drink, would, if they found the trough empty, tease this horse that knew how to pump; they would get around him, and bite and kick him till he would pump some water for them.

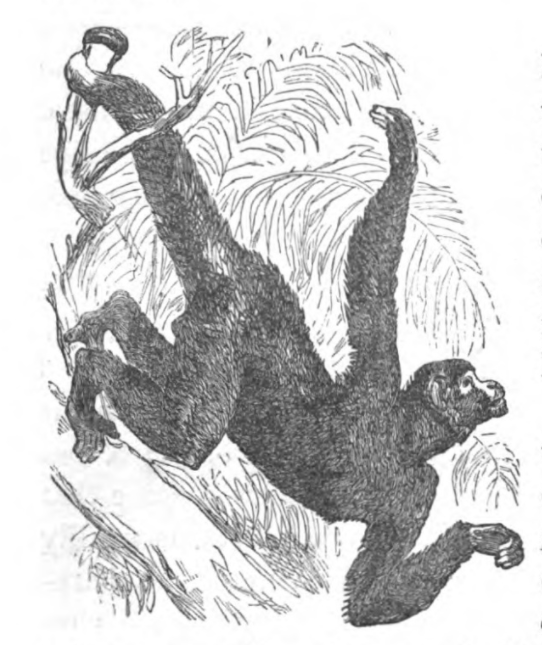

Monkeys have four things like hands. They are halfway between hands and feet. With these they are very skillful at climbing. There are some kinds of monkeys, as the one represented here, that use their tails in climbing as a sort of fifth hand.

The cat uses for hands some times her paws, with their sharp claws, sometimes her teeth, and sometimes both together. She climbs with her claws. She catches things with them—mice, rats, or any thing that you hold out for her to run after. She strikes with her paws, just as angry children and men sometimes do with their hands. When the cat moves her kittens from one place to another, she takes them up with her teeth by the nape of the neck. There is no other way in which she can do it. She cannot walk on her hind feet and carry them with her fore paws. It seems as if it would hurt a kitten to carry it in the way that she does, but it does not.

When a squirrel nibbles a nut to make a hole in it, he holds it between his two fore

paws like hands. So also does the dormouse, which you see here.

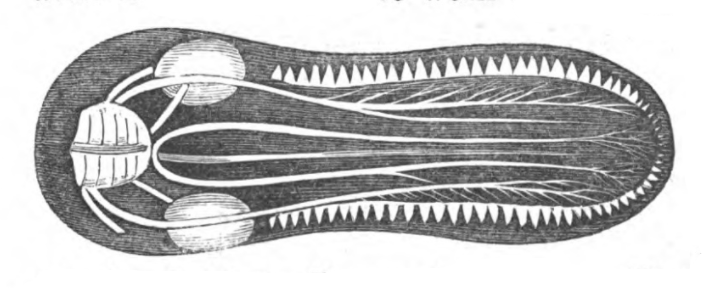

The bill[2] of a bird is used as its hand. It gathers with it its food to put into its crop. When you throw corn out to the hens, how fast they pick it up, and send it down into their crops to be well soaked! The humming-bird has a very long bill, and in it lies a long, slender, and very delicate tongue. As he poises himself in the air before a flower, his wings fluttering so quickly that you can not see them, he runs his bill into the bottom of the flower where the honey is, and puts his little long tongue into it. The bill of the duck is made in a peculiar way. You know that it gets its food under water in the mud. It can not see, therefore, what it gets. It has to work altogether by feeling, and it has nerves in its bill for this purpose.

Here is a picture of its bill, showing the nerves branching out on it. You see, too, a row of pointed things all around the edge. They look like teeth, but they are not teeth. They are used by the duck in finding its food. It manages in this way: it thrusts its bill down, and as it takes it up it is full of mud. Now mixed with the mud are things which the duck lives on. The nerves tell the duck what is good, and it lets all the rest go out between the prickles. It is a sort of sifting operation, the nerves in the sieve[3] taking good care that nothing good shall pass out.

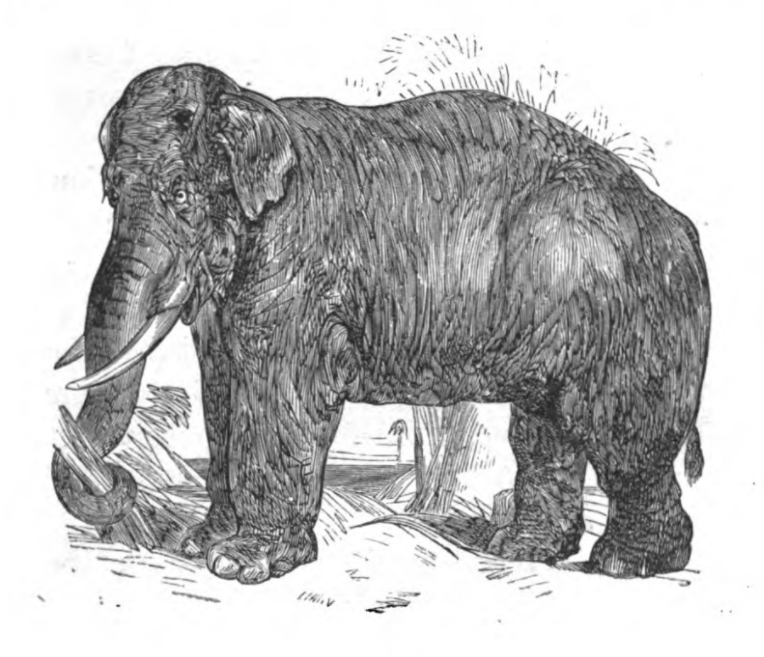

One of the most remarkable things used in place of a hand is the trunk of the elephant. The variety of uses to which the elephant puts this organ is very wonderful. It can strike very heavy blows with it. It can wrench off branches of trees, or even pull up trees by the roots, by winding its trunk around them to grasp them, as you see it is doing here. It is its arm with which it carries its young. It is amusing to see an old elephant carefully wind its trunk around a new-born elephant, and carry it gently along.

But the elephant can also do some very little things with his trunk. You see in this picture that there is a sort of finger at the very end of the trunk. It is a very nimble[4] finger, and with it this monstrous animal can do a great variety of little things. He will take with it little bits of bread, and other kinds of food that you hand to him, and put them into his mouth. He will take up a piece of money from the ground as easily as you can with your fingers. It is with this finger, too, that he feels of things just as you do with your fingers. I once saw an elephant take a whip with this fingered end of his trunk, and use it as handily as a teamster[5], very much to the amusement of the spectators.

The elephant can reach a considerable distance with his trunk. And this is necessary, because he has so very short a neck. He could not get at his food without his long trunk. Observe, too, how he can turn this trunk about in every direction, and twist it about in every way. It is really a wonderful piece of machinery. Cuvier, a great French anatomist, says that there are over thirty thousand little muscles in it. All this army of muscles receive their orders by nerves from the mind in the brain, and how well they obey them!

You see that there are two holes in the end of the trunk. Into these he can suck water, and thus fill his trunk with it. Then he can turn the end of his trunk into his mouth and let the water run down his throat. But sometimes he uses the water in his trunk in another way; he blows it out through his trunk with great force. He does this when he wants to wash himself, directing his trunk in such a way that the water will pour over him. He some times blows the water out in play, for even such great animals have sports like children. Sometimes, too, he blows the water on people that he does not like. You perhaps have read the story of the tailor[6] who pricked the trunk of an elephant with his needle. The elephant, as he was passing, put his trunk into the shop window, hoping that the tailor would give him something to eat. He was angry at being pricked, and was determined to make the man sorry for doing such an unkind act. As his keeper led him back past the same window, he poured upon the tailor his trunk full of dirty water, which he had taken from a puddle for this purpose.

hooker, worthington. 1871. “Chapter XXII: What Animals Use for hands.” In The child’s book of nature: for the use of families and schools: intended to aid mothers and teachers in training children in the observation of nature: in three parts, 102-108. New York: Harper & Brothers. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/101795903.

[1] Wide or thick in build.

[2] Also known as the beak of a bird.

[3] A bowl-shaped object usually used to strain or separate larger solids from liquids and small solids.

[4] Quick-moving and light.

[5] A person who drives a team of animals.

[6] Hooker is referring to the Indian fable “The Revenge of the Elephant,” which can be found with other Indian animal fables in the Panchatantra. In some versions of the story, it is the tailor’s son who pricks the elephant’s trunk with a needle and learns the error of his ways.

Contexts

The Child’s Book of Nature is a natural science book for children written in three parts: Part I. Plants, Part II. Animals, and Part III. Air, Water, Heat, Light, &c. In the original Preface of The Child’s Book of Nature, Hooker explains his approach to writing science for a juvenile audience and affirms his belief in the importance of science education:

Children are busy observers of natural objects, and have many questions to ask about them. But their inquisitive observation is commonly repressed, instead of being encouraged and guided. The chief reason for this unnatural course is, that parents and teachers are not in possession of the information which is needed for the guidance of children in the observation of nature. They have not themselves been taught aright, and therefore are not able to teach others. In their own education the observation of nature has been almost entirely excluded; and they are, therefore, unprepared to teach a child in regard to the simplest natural phenomena. Here is a radical error in education. When we put a child into the school-room, to be drilled in spelling, reading, arithmetic, geography, etc., we effectually shut him in from all the varied and interesting objects of nature, which he is so naturally inclined to observe and study. These are very seldom made the subjects of instruction in childhood. And even at the fireside the deficiency is nearly as great as it is in the school-room.

A similar defect appears to a great extent through the whole course of education. The study of the wonderful phenomena which are all around us and within us, is, for the most part, neglected, except by the few whose inclinations to it are so strong that they can not be repressed. This defect is well illustrated in a remark which was made by a mother in relation to her own education. When at school she stood at the head of her class, and excelled particularly in mathematics. Her remark was, that she every day regretted that much of the time she had given to the study of mathematics had not been spent in learning what would enable her to answer the continual questions of her children. Even when the natural sciences are taught, the mode of teaching them is generally ineffectual. The knowledge which the mass of pupils in our higher schools gain of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry, Botany, and Physiology, is very deficient.

There should be a thorough change in this respect in the whole course of education, beginning in childhood. The natural sciences should be made prominent among the studies even of young children, who, in other words, should be encouraged and guided in that observation of nature to which they are generally so much inclined. In the different departments of natural science there are multitudes of facts or phenomena in which children readily become interested, when they are properly explained. In this little book my object is to supply the mother and the teacher with the means of introducing the child into one department of natural science—that which relates to the vegetable world, or vegetable physiology. With this view, I have endeavored to select those points only which the child will fully understand, and in which he will be interested. But this selection has by no means shut me up within narrow limits. I have been surprised at the amount of knowledge in this interesting study that can be satisfactorily communicated to the mind of a child. While the fundamental points in vegetable physiology are quite fully developed in this book, I have avoided as far as possible all technical terms. These can be learned when the pupil becomes old enough to profit by learning them. The facts, the phenomena, are what the child wants to understand ; and these can be communicated in the simplest language, so that a child of about seven or eight, or perhaps even six years, can readily be made to comprehend them.

I begin with the most simple and obvious facts—those which relate to flowers—and go on through fruits, seeds, leaves, roots, etc., step by step, until, at the latter part of the book, the circulation of the sap, and other points at first view complicated, are made perfectly intelligible. By this gradual unfolding of the subject, many points are made clear to the child, which are not fully understood by many of those who in riper years have studied botany; for in the common mode of teaching this science the mere technicalities of it are made prominent, while the interesting facts which vegetable physiology presents to us in such variety receive but little attention.

The best time to use this book in teaching is during the summer, because then every thing can be illustrated by specimens from the field and the garden, and the teacher can amplify upon what I have given. For example, when the lesson is to be on leaves, the teacher can request her scholars to bring as many different kinds of leaves as they can find; and she can point out their differences after the same plan that I have adopted, but in a much more extended manner. Indeed, if the teacher catch her self the true spirit of observation, she will be continually led in her teachings to add facts of her own gathering to those which I have presented.

I believe that there are few terms in the book that can not be readily understood by the child. A little explanation may sometimes be necessary on the part of the teacher, especially when the same word is used as meaning more at one time than at another. For example, the word plant is used sometimes, as in the title of this book, to include every thing that is vegetable; while at another time it is used to distinguish certain forms of vegetables from others, as in the expression plants and trees.

I have made such a division into chapters as will place each subject by itself, and at the same time, for the most part, give lessons of a proper length for the learner. I have placed questions at the end of each chapter, for convenience in instruction. Of course the teacher or parent will vary them as she sees fit, to accommodate the capacities of those whom she teaches.

“What Animals Use for Hands” is the twenty-second chapter of Part II. Animals and is included in this anthology as an example of late nineteenth-century American efforts to promote children’s science education.

Resources for Further Study

- Viṣṇuśarman. 2013. Panchatantra : 51 Short Stories with Moral (Illustrated). Edited by Praful B and Maharshi G. Place of publication not identified: Vyanst.

- Longbottom, John E., and Philip H. Butler. 1999. “Why Teach Science? Setting Rational Goals for Science Education.” Science Education, 83, no. 4: 473-492. https://doi-org.libproxy.uncg.edu/10.1002/(SICI)1098-237X(199907)83:4<473::AID-SCE5>3.0.CO;2-Z.

- Davies, Dan, and Deb McGregor. 2016. Teaching Science Creatively. London: Routledge.

- Kohlstedt, Sally Gregory. 2010. Teaching Children Science: Hands-On Nature Study in North America, 1890-1930. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

Pedagogy

Hooker provides guided reading questions with each chapter of his book. The questions for Chapter XXII are as follows:

What is said about the dog? What answer for hands to the cow and the horse? Tell the anecdotes about horses. What does the cat use for hands, and how? What is said about the squirrel and dormouse? What is the bird’s hand? Tell about feeding the hens. Tell about the bill of the duck. What is told of the humming-bird? Mention some of the variety of uses to which the elephant can put his trunk. What is said about the finger on the end of it? Why does the elephant need so long a trunk? What is said about the muscles in it? How does the elephant drink? How does he wash himself? Tell about the tailor.

Hooker also suggests that children will find the study of science, and particularly animal science, more interesting if information is presented in comparison to their own physiology and lived experiences. To that end, you might ask your child or student to consider the following questions:

- How is [animal]’s body like mine? How is it different?

- What can I do with my body that [animal] cannot?

- Can [animal] do something with their body that I cannot? Why might they have that ability if I don’t?