Zuni Creation Cycle[1]

By Various Authors

Annotations by Ian McLaughlin

The Beginning of Newness

Before the beginning of the New-making, the All-father Father alone had being. Through ages there was nothing else except black darkness.

In the beginning of the New-making, the All-father Father thought outward in space, and mists were created and up-lifted. Thus through his knowledge he made himself the Sun who was thus created and is the great Father. The dark spaces brightened with light. The cloud mists thickened and became water.

From his flesh, the Sun-father created the Seed-stuff of worlds, and he himself rested upon the waters. And these two, the Four-fold-containing Earth-mother and the All-covering Sky-father, the surpassing beings, with power of changing their forms even as smoke changes in the wind, were the father and mother of the soul beings.

Then as man and woman spoke these two together. “Behold!” said Earth-mother, as a great terraced bowl appeared at hand, and within it water, “This shall be the home of my tiny children. On the rim of each world-country in which they wander, terraced mountains shall stand, making in one region many mountains by which one country shall be known from another.”

Then she spat on the water and struck it and stirred it with her fingers. Foam gathered about the terraced rim, mounting higher and higher. Then with her warm breath she blew across the terraces. White flecks of foam broke away and floated over the water. But the cold breath of Sky-father shattered the foam and it fell downward in fine mist and spray.

Then Earth-mother spoke: “Even so shall white clouds float up from the great waters at the borders of the world, and clustering about the mountain terraces of the horizon, shall be broken and hardened by thy cold. Then will they shed downward, in rain-spray, the water of life, even into the hollow places of my lap. For in my lap shall nestle our children, man-kind and creature-kind, for warmth in thy coldness.”

So even now the trees on high mountains near the clouds and Sky-father, crouch low toward Earth mother for warmth and protection. Warm is Earth-mother, cold our Sky-father.

Then Sky-father said, “Even so. Yet I, too, will be helpful to our children.” Then he spread his hand out with the palm downward and into all the wrinkles of his hand he set the semblance of shining yellow corn-grains; in the dark of the early world-dawn they gleamed like sparks of fire.

“See,” he said, pointing to the seven grains between his thumb and four fingers, “our children shall be guided by these when the Sun-father is not near and thy terraces are as darkness itself. Then shall our children be guided by lights.” So Sky-father created the stars. Then he said, “And even as these grains gleam up from the water, so shall seed grain like them spring up from the earth when touched by water, to nourish our children.” And thus they created the seed-corn. And in many other ways they devised for their children, the soul-beings.

But the first children, in a cave of the earth, were unfinished. The cave was of sooty blackness, black as a chimney at night time, and foul. Loud became their murmurings and lamentations, until many sought to escape, growing wiser and more man-like.

But the earth was not then as we now see it. Then Sun-father sent down two sons (sons also of the Foam-cap), the Beloved Twain, Twin Brothers of Light, yet Elder and Younger, the Right and the Left, like to question and answer in deciding and doing. To them the Sun-father imparted his own wisdom. He gave them the great cloud-bow, and for arrows the thunderbolts of the four quarters. For buckler, they had the fog-making shield, spun and woven of the floating clouds and spray. The shield supports its bearer, as clouds are supported by the wind, yet hides its bearer also. And he gave to them the fathership and control of men and of all creatures. Then the Beloved Twain, with their great cloud-bow lifted the Sky-father into the vault of the skies, that the earth might become warm and fitter for men and creatures. Then along the sun-seeking trail, they sped to the mountains westward. With magic knives they spread open the depths of the mountain and uncovered the cave in which dwelt the unfinished men and creatures. So they dwelt with men, learning to know them, and seeking to lead them out.

Now there were growing things in the depths, like grasses and vines. So the Beloved Twain breathed on the stems, growing tall toward the light as grass is wont to do, making them stronger, and twisting them upward until they formed a great ladder by which men and creatures ascended to a second cave.

Up the ladder into the second cave-world, men and the beings crowded, following closely the Two Little but Mighty Ones. Yet many fell back and were lost in the darkness. They peopled the under-world from which they escaped in after time, amid terrible earth shakings.

In this second cave it was as dark as the night of a stormy season, but larger of space and higher. Here again men and the beings increased, and their complainings grew loud. So the Twain again increased the growth of the ladder, and again led men upward, not all at once, but in six bands, to become the fathers of the six kinds of men, the yellow, the tawny gray, the red, the white, the black, and the mingled. And this time also many were lost or left behind.

Now the third great cave was larger and lighter, like a valley in starlight. And again they increased in number. And again the Two led them out into a fourth cave. Here it was light like dawning, and men began to perceive and to learn variously, according to their natures, wherefore the Twain taught them first to seek the Sun-father.

Then as the last cave became filled and men learned to understand, the Two led them forth again into the great upper world, which is the World of Knowing Seeing.

The Men of the Early Times

Eight years was but four days and four nights when the world was new. While such days and nights continued, men were led out, in the night-shine of the World of Seeing. For even when they saw the great star, they thought it the Sun-father himself, it so burned their eye-balls.

Men and creatures were more alike then than now. Our fathers were black, like the caves they came from; their skins were cold and scaly like those of mud creatures; their eyes were goggled like an owl’s; their ears were like those of cave bats; their feet were webbed like those of walkers in wet and soft places; they had tails, long or short, as they were old or young. Men crouched when they walked, or crawled along the ground like lizards. They feared to walk straight, but crouched as before time they had in their cave worlds, that they might not stumble or fall in the uncertain light.

When the morning star arose, they blinked excessively when they beheld its brightness and cried out that now surely the Father was coming. But it was only the elder of the Bright Ones, heralding with his shield of flame the approach of the Sun-father. And when, low down in the east, the Sun-father himself appeared, though shrouded in the mist of the world-waters, they were blinded and heated by his light and glory. They fell down wallowing and covered their eyes with their hands and arms, yet ever as they looked toward the light, they struggled toward the Sun as moths and other night creatures seek the light of a camp fire. Thus they became used to the light. But when they rose and walked straight, no longer bending, and looked upon each other, they sought to clothe themselves with girdles and garments of bark and rushes. And when by walking only upon their hinder feet they were bruised by stone and sand, they plaited sandals of yucca fibre.

The Search for the Middle and the Hardening of the World

As it was with the first men and creatures, so it was with the world. It was young and unripe. Earthquakes shook the world and rent it. Demons and monsters of the under-world fled forth. Creatures became fierce, beasts of prey, and others turned timid, becoming their quarry. Wretchedness and hunger abounded and black magic. Fear was everywhere among them, so the people, in dread of their precious possessions, became wanderers, living on the seeds of grass, eaters of dead and slain things. Yet, guided by the Beloved Twain, they sought in the light and under the pathway of the Sun, the Middle of the world, over which alone they could find the earth at rest (1). (Ed. note 1: The earth was flat and round, like a plate.)

When the tremblings grew still for a time, the people paused at the First of Sitting Places. Yet they were still poor and defenceless and unskilled, and the world still moist and unstable. Demons and monsters fled from the earth in times of shaking, and threatened wanderers.

Then the Two took counsel of each other. The Elder said the earth must be made more stable for men and the valleys where their children rested. If they sent down their fire bolts of thunder, aimed to all the four regions, the earth would heave up and down, fire would, belch over the world and burn it, floods of hot water would sweep over it, smoke would blacken the daylight, but the earth would at last be safer for men.

So the Beloved Twain let fly the thunderbolts.

The mountains shook and trembled, the plains cracked and crackled under the floods and fires, and the hollow places, the only refuge of men and creatures, grew black and awful. At last thick rain fell, putting out the fires. Then water flooded the world, cutting deep trails through the mountains, and burying or uncovering the bodies of things and beings. Where they huddled together and were blasted thus, their blood gushed forth and flowed deeply, here in rivers, there in floods, for gigantic were they. But the blood was charred and blistered and blackened by the fires into the black rocks of the lower mesas (2). (Ed. note 2: Lava) There were vast plains of dust, ashes, and cinders, reddened like the mud of the hearth place. Yet many places behind and between the mountain terraces were unharmed by the fires, and even then green grew the trees and grasses and even flowers bloomed. Then the earth became more stable, and drier, and its lone places less fearsome since monsters of prey were changed to rock.

But ever and again the earth trembled and the people were troubled.

“Let us again seek the Middle,” they said. So they travelled far eastward to their second stopping place, the Place of Bare Mountains.

Again the world rumbled, and they travelled into a country to a place called Where-tree-boles-stand-in-the-midst-of-waters. There they remained long, saying, “This is the Middle.” They built homes there. At times they met people who had gone before, and thus they learned war. And many strange things happened there, as told in speeches of the ancient talk.

Then when the earth groaned again, the Twain bade them go forth, and they murmured. Many refused and perished miserably in their own homes, as do rats in falling trees, or flies in forbidden food.

But the greater number went forward until they came to Steam-mist-in-the-midst-of-waters. And they saw the smoke of men’s hearth fires and many houses scattered over the hills before them. When they came nearer, they challenged the people rudely, demanding who they were and why there, for in their last standing-place they had had touch of war.

“We are the People of the Seed,” said the men of the hearth-fires, “born elder brothers of ye, and led of the gods.”

“No,” said our fathers, “we are led of the gods and we are the Seed People…”

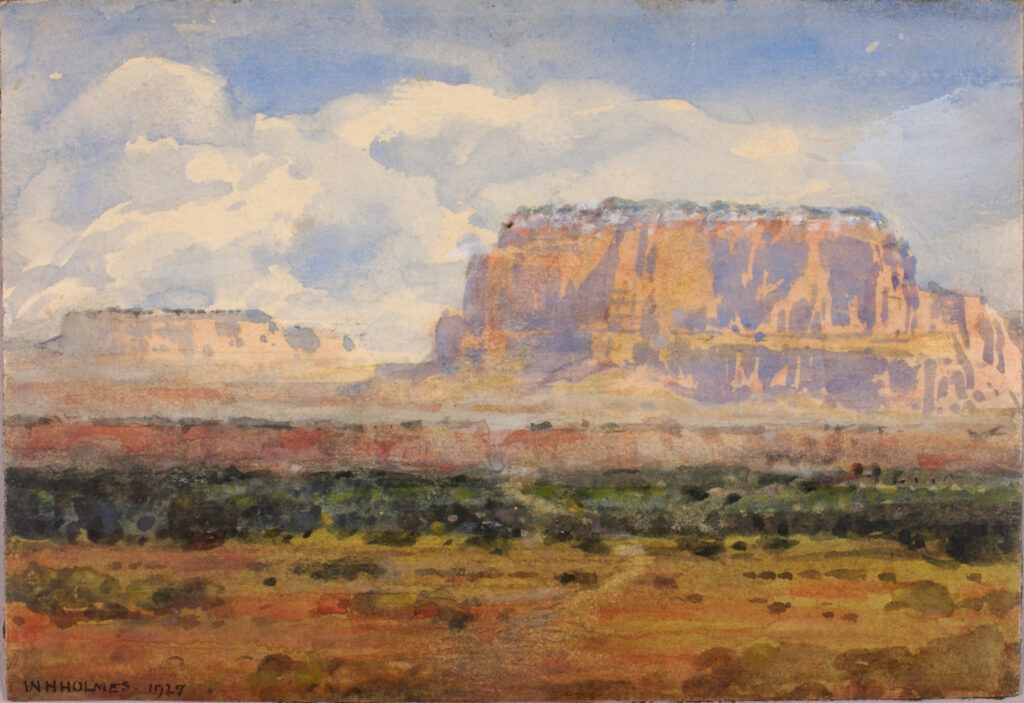

1924, Smithsonian American Art Museum and its Renwick Gallery, Washington, D.C.

Long lived the people in the town on the sunrise slope of the mountains of Kahluelawan, until the earth began to groan warningly again. Loath were they to leave the place of the Kaka and the lake of their dead. But the rumbling grew louder and the Twain Beloved called, and all together they journeyed eastward, seeking once more the Place of the Middle. But they grumbled amongst themselves, so when they came to a place of great promise, they said, “Let us stay here. Perhaps it may be the Place of the Middle.”

So they built houses there, larger and stronger than ever before, and more perfect, for they were strong in numbers and wiser, though yet unperfected as men. They called the place “The Place of Sacred Stealing.”

Long they dwelt there, happily, but growing wiser and stronger, so that, with their tails and dressed in the skins of animals, they saw they were rude and ugly.

In chase or in war, they were at a disadvantage, for they met older nations of men with whom they fought. No longer they feared the gods and monsters, but only their own kind. So therefore the gods called a council.

“Changed shall ye be, oh our children,” cried the Twain. “Ye shall walk straight in the pathways, clothed in garments, and without tails, that ye may sit more straight in council, and without webs to your feet, or talons on your hands.”

So the people were arranged in procession like dancers. And the Twain with their weapons and fires of lightning shored off the forelocks hanging down over their faces, severed the talons, and slitted the webbed fingers and toes. Sore was the wounding and loud cried the foolish, when lastly the people were arranged in procession for the razing of their tails.

But those who stood at the end of the line, shrinking farther and farther, fled in their terror, climbing trees and high places, with loud chatter. Wandering far, sleeping ever in tree tops, in the far-away Summerland, they are sometimes seen of far-walkers, long of tail and long handed, like wizened men-children.

But the people grew in strength, and became more perfect, and more than ever went to war. They grew vain. They had reached the Place of the Middle. They said, “Let us not wearily wander forth again even though the earth tremble and the Twain bid us forth.”

And even as they spoke, the mountain trembled and shook, though far-sounding.

But as the people changed, changed also were the Twain, small and misshapen, hard-favored and unyielding of will, strong of spirit, evil and bad. They taught the people to war, and led them far to the eastward.

At last the people neared, in the midst of the plains to the eastward, great towns built in the heights. Great were the fields and possessions of this people, for they knew how to command and carry the waters, bringing new soil. And this, too, without hail or rain. So our ancients, hungry with long wandering for new food, were the more greedy and often gave battle.

It was here that the Ancient Woman of the Elder People, who carried her heart in her rattle and was deathless of wounds in the body, led the enemy, crying out shrilly. So it fell out ill for our fathers. For, moreover, thunder raged and confused their warriors, rain descended and blinded them, stretching their bow strings of sinew and quenching the flight of their arrows as the flight of bees is quenched by the sprinkling plume of the honey-hunter. But they devised bow strings of yucca and the Two Little Ones sought counsel of the Sun-father who revealed the life-secret of the Ancient Woman and the magic powers over the under-fires of the dwellers of the mountains, so that our enemy in the mountain town was overmastered. And because our people found in that great town some hidden deep in the cellars, and pulled them out as rats are pulled from a hollow cedar, and found them blackened by the fumes of their war magic, yet wiser than the common people, they spared them and received them into their next of kin of the Black Corn….

But the tremblings and warnings still sounded, and the people searched for the stable Middle.

Now they called a great council of men and the beasts, birds, and insects of all kinds. After a long council it was said,

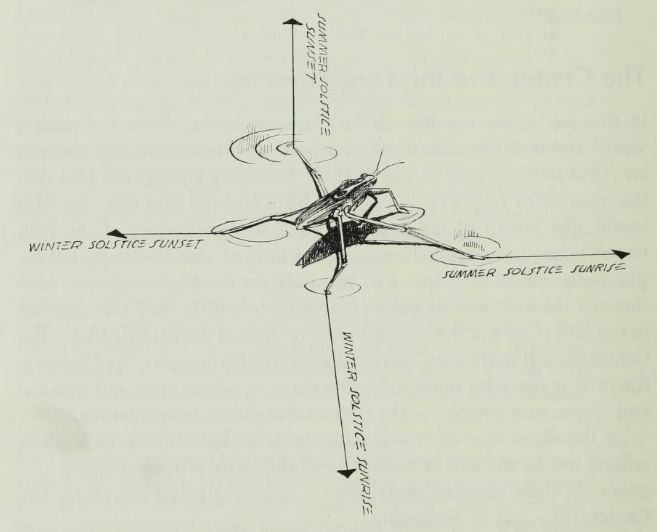

“Where is Water-skate? He has six legs, all very long. Perhaps he can feel with them to the uttermost of the six regions, and point out the very Middle.”

American Indian by R. A. Williamson, p. 66.

So Water-skate was summoned. But lo! It was the Sun-father in his likeness which appeared. And he lifted himself to the zenith and extended his fingerfeet to all the six regions, so that they touched the north, the great waters; the west, and the south, and the east, the great waters; and to the northeast the waters above, and to the southwest the waters below. But to the north his finger foot grew cold, so he drew it in. Then gradually he settled down upon the earth and said, “Where my heart rests, mark a spot, and build a town of the Mid-most, for there shall be the Mid-most Place of the Earth-mother.”

And his heart rested over the middle of the plain and valley of Zuni. And when he drew in his finger-legs, lo! there were the trail-roads leading out and in like stays of a spider’s nest, into and from the mid-most place he had covered.

Here because of their good fortune in finding the stable Middle, the priest father called the town the Abiding-place-of-happy-fortune.

various authors. “The Beginning of Newness,” “The men of the early times,” “The Search for the Middle and the Hardening of the World.” In MYTHS AND LEGENDS OF CALIFORNIA AND THE OLD SOUTHWEST, Ed. Katharine Berry Judson. Chicago: A.C. MCCLURG & CO., 1912.

[1] These three stories constitute a history of the Earth and the Zuni people from the beginning of creation to the foundation of their pueblo.

Contexts

Creation myths, or cosmogonies, are one of the few universals. Although the how, why, where, and when of creation varies from culture to culture, they all account for the existence of the world around them. Some cultures attribute the creation of the world to one or more divine beings; others say it emanates from a source. In the case of the Zuni Creation Cycle, the story places their pueblo in the geographical Middle of the World, where the gods wish them to be.

Resources for Further Study

- Zunian Lullaby is another example of Zuni oral tradition.

- For more information about contemporary Zuni culture, visit the Pueblo of Zuni website.