The Antelope Boy

Collected by Charles Lummis

Annotations by Ian McLAughlin

Once upon a time there were two towns of the Tée-wahn, called Nah-bah-tóo-too-ee (white village) and Nah-choo-rée-too-ee (yellow village). A man of Nah-bah-tóo-too-ee and his wife were attacked by Apaches while out on the plains one day and took refuge in a cave, where they were besieged. And there a boy was born to them. The father was killed in an attempt to return to his village for help; and starvation finally forced the mother to crawl forth by night seeking roots to eat. Chased by the Apaches, she escaped to her own village, and it was several days before she could return to the cave—only to find it empty.

The baby had begun to cry soon after her departure. Just then a Coyote[1] was passing, and heard. Taking pity on the child, he picked it up and carried it across the plain until he came to a herd of antelopes. Among them was a Mother-Antelope that had lost her fawn; and going to her the Coyote said:

“Here is an ah-bóo (poor thing) that is left by its people. Will you take care of it?”

The Mother-Antelope, remembering her own baby, with tears said “Yes” and at once adopted the tiny stranger, while the Coyote thanked her and went home.

So the boy became as one of the antelopes, and grew up among them until he was about twelve years old. Then it happened that a hunter came out from Nah-bah-tóo-too-ee for antelopes, and found this herd. Stalking them carefully, he shot one with an arrow. The rest started off, running like the wind; but ahead of them all, as long as they were in sight, he saw a boy! The hunter was much surprised, and, shouldering his game, walked back to the village, deep in thought. Here he told the Cacique[2] what he had seen. Next day the crier was sent out to call upon all the people to prepare for a great hunt, in four days,[3] to capture the Indian boy who lived with the antelopes.

While preparations were going on in the village, the antelopes in some way heard of the intended hunt and its purpose. The Mother-Antelope was very sad when she heard it, and at first would say nothing. But at last she called her adopted son to her and said: “Son you have heard that the people of Nah-bah-tóo-too-ee are coming to hunt. But they will not kill us; all they wish is to take you. They will surround us, intending to let all the antelopes escape from the circle. You must follow me where I break through the line, and your real mother will be coming on the northeast side in a white manta (robe). I will pass close to her, and you must stagger and fall where she can catch you.”

On the fourth day all the people went out upon the plains. They found and surrounded the herd of antelopes, which ran about in a circle when the hunters closed upon them. The circle grew smaller and the antelopes began to break through; but the hunters paid no attention to them, keeping their eyes upon the boy. At last he and his antelope mother were the only ones left, and when she broke through the line on the northeast he followed her and fell at the feet of his own human mother, who sprang forward and clasped him in her arms.

Amid great rejoicing he was taken to Nah-bah-tóo-too-ee, and there he told the principales[4] how he had been left in the cave, how the Coyote had pitied him, and how the Mother-Antelope had reared him as her own son.

It was not long before all the country round about heard of the Antelope Boy and of his marvelous fleetness of foot. You must know that the antelpes never comb their hair, and while among them the boy’s head had grown very bushy. So the people called him Pée-hleh-o-wah-wée-deh (big-headed little boy).

Among the other villages that heard of his prowess was Nah-choo-rée-too-ee, all of whose people “had the bad road.”[5] They had a wonderful runner named Pée-k’hoo (Deer-foot), and very soon they sent a challenge to Nah-bah-tóo-too-ee for a championship race. Four days were to be given for preparation, to make bets, and the like.

The race was to be around the world.[6] Each village was to stake all its property and the lives of all its people on the result of the race. So powerful were the witches of Nah-choo-rée-too-ee that they felt safe in proposing so serious a stake; and the people of Nah-bah-tóo-too-ee were ashamed to decline the challenge.

The day came and the starting point was surrounded by all the people of the two villages, dressed in their best. On each side were huge piles of ornaments and dresses, stores of grain, and all the other property of the people. The runner for the yellow village was a tall, sinewy athlete, strong in his early manhood; and when the Antelope Boy appeared for the other side, the witches set up a howl of derision and began to strike their rivals and jeer at them, saying, “Pooh! We might as well begin to kill you now! What can that óo-deh (little thing) do?

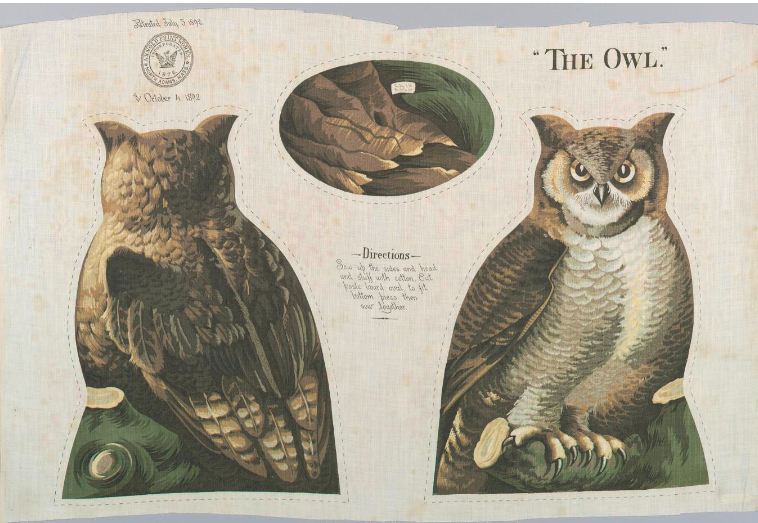

At the word “Hái-ko!” (“Go!”) the two runners started toward the east like the wind. The Antelope Boy soon forged ahead; but Deer-foot, by his witchcraft, changed himself into a hawk and flew lightly over the lad, saying, “We do this way to each other!”[7] The Antelope Boy kept running, but his heart was very heavy, for he knew that no feet could equal the swift flight of the hawk.

But just as he came half-way to the east, a Mole came up from its burrow and said: “My son, where are you going so fast with a sad face?”

The lad explained that the race was for the property and the lives of all his people; and that the witch runner had turned into a hawk and left him far behind.

“Then, my son,” said the Mole, “I will be he that shall help you. Only sit down here a little while, and I will give you something to carry.”

The boy sat down, and the Mole diced into the hold, but soon came back with four cigarettes.[8]

Holding them out the Mold said, “Now, my son, when you have reached the east and turned north, smoke one; when you have reached the north and turn west, smoke another; when you turn south, another and when you turn east again, another. Hái-ko!”

The boy ran on, and soon reached the east. Turning his face to the north he smoked the first cigarette. No sooner was it finished than he became a young antelope; and at the same instant a furious rain began. Refreshed by the cool drops, he started like an arrow from the bow. Half-way to the north he came to a large tree; and there sat the hawk, drenched and chilled, unable to fly, and crying piteously.

“Now, friend, we too do this to each other,” called the boy-antelope as he dashed past. But just as he reached the north, the hawk—which had become dry after the short rain—caught up and passed him, saying, “We too do this to each other!” The boy-antelope turned westward, and smoked the second cigarette; and at once another terrific rain began.[9] Half-way to the west he again passed the hawk shivering and crying in a tree, and unable to fly; but as he was about to turn to the south, the hawk passed him with the customary taunt. The smoking of the third cigarette brought another storm, and again the antelope passed the wet hawk half-way, and again the hawk dried its feathers in time to catch up and pass him as he was turning to the east for the home-stretch. Here again the boy-antelope stopped and smoked a cigarette—the fourth and last. Again a short, hard rain came and again he passed the water-bound hawk half-way.

Knowing of the witchcraft of their neighbors, the people of Nah-bah-tóo-too-ee had made the condition that, in whatever shape the racers might run the rest of the course, they must resume human form upon arrival at a certain hill upon the fourth turn, which was in sight of the goal. The last wetting of the hawk’s feathers delayed it so that the antelope reached the hill just ahead; and there, resuming their natural shapes, the two runners came sweeping down the home-stretch, straining at every nerve. But the Antelope Boy gained at each stride. When they saw him, the witch-people felt confident that he was their champion, and again began to push, and taunt, and jeer at their others. But when the little Antelope Boy sprang lightly across the line, far ahead of Deer-foot, their joy turned to mourning.

The people of Nah-bah-tóo-too-ee burned all the witches upon the spot, in a great pile of corn; but somehow one escaped, and from him come all the witches that trouble us to this day.

The property of the witches was taken to Nah-bah-tóo-too-ee; and as it was more than that village could hold, the surplus was sent to Shee-eh-whíb-bak (Isleta),[10] where we enjoy it to this day; and later the people themselves moved here. And even now, when we dig in that little hill on the other side of the charco (pools), we find charred corn-cobs, where our forefathers burned the witch-people of the yellow village.

LUMMIS, CHARLES FLETCHER. THE MAN WHO MARRIED THE MOON AND OTHER PUEBLO INDIAN FOLK-STORIES. THE MAN WHO MARRIED THE MOON AND OTHER PUEBLO INDIAN FOLK-STORIES, BY CHARLES LUMIS. NEW YORK, NY: THE CENTURY CO., 1894. HTTPS://HDL.HANDLE.NET/2027/UC2.ARK:/13960/T3WS8JC1P.

[1] The small prairie-wolf. (Lummis)

Coyote Tales of the Southwest has more coyote stories.

[2] The highest religious official (Lummis)

[3] Four is the most important number in many Native American cultures. It stands for a cycle of fertility, being found in the four ages of man, the four seasons, and the four cardinal directions.

[4] The old men who are the congress of the pueblo (Lummis)

[5] That is, were witches (Lummis)

[6] The Pueblos believed it was an immense plain whereon the racers were to race over a square course—to the extreme east, then to the extreme north, and so on, back to the starting point. (Lummis)

[7] A common Indian taunt, either good-natured or bitter, to the loser of a game or to a conquered enemy (Lummis)

[8] These are made by putting a certain weed called pee-én-hleh into hollow reeds. (Lummis)

[9]The cigarette plays an important part in the Pueblo folk-stories,—they never had the pipe of the Northern Indians, —and all the rain-clouds are supposed to come from its smoke. (Lummis)

[10] Isleta is the largest of the Tée-wahn pueblos and the second-largest pueblo overall.

Contexts

Stories of humans raised by animals are almost as old as civilization. The story of Romulus and Remus from Roman mythology, Kippling’s Mowgli, and Incident at Hawk’s Hill (1971) by naturalist and writer Allan W. Eckert all use this trope. In most cases, this connection to nature is accompanied by animal-like abilities, such as ferocity in battle, literally talking to animals, or, in the case of “The Antelope Boy” running as fast as an antelope.

Resources for Further Study

- “The Sacred Hoop: A Contemporary Perspective on Native American Literature” from The Sacred Hoop: Recovering the Feminine in American Indian Traditions by Paula Gunn Allen is a great essay on how to read Native Literature as a non-Native.

- The Man Who Married the Moon by Charles Lummis (also published under the title Pueblo Indian folk-stories) is an excellent resource on the stories and the culture of the Tée-wahn pueblos of New Mexico.

- “Locating the Human in Performance” from Affect, Animals, and Autists: Feeling Around the Edges of the Human in Performance by Marla Carlson touches on the idea of the feral child and how it shapes our understanding of civilization.

Pedagogy

Despite the cigarette imagery, this story is great for a comparative reading with other stories of children raised by animals, such as those listed in the Contexts section above.

Contemporary Connections

Avatar: The Last Airbender features a character raised by giant badger-like creatures.

The Jungle Book by Rudyard Kippling and the subsequent movies, including the most recent Disney version, have captured imaginations for more than a century.