The Boy Who Became A God

Collected by Katharine Berry Judson

Annotations by Ian McLaughlin

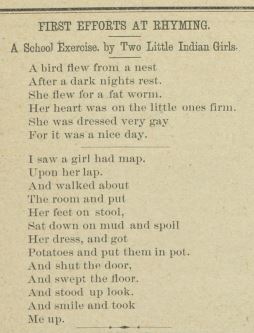

Mythical Sand Painting of the Navajo Indians by James Stevenson (2006)[1]

Navajo[1] (New Mexico)

The Tolchini,[3] a clan of the Navajos,[4] lived at Wind Mountains.[5] One of them used to take long visits into the country. His brothers thought he was crazy. The first time on his return, he brought with him a pine bough; the second time, corn. Each time he returned he brought something new and had a strange story to tell. His brothers said: “He is crazy. He does not know what he is talking about.”

Now the Tolchini left Wind Mountains and went to a rocky foothill east of the San Mateo Mountain. They had nothing to eat but seed grass. The eldest brother said, “Let us go hunting,” but they told the youngest brother not to leave camp. But five days and five nights passed, and there was no word. So he followed them.

After a day’s travel he camped near a canon, in a cavelike place. There was much snow but no water so he made a fire and heated a rock, and made a hole in the ground. The hot rock heated the snow and gave him water to drink. Just then he heard a tumult over his head, like people passing. He went out to see what made the noise and saw many crows crossing back and forth over the canon. This was the home of the crow, but there were other feathered people there, and the chaparral cock[6]. He saw many fires made by the crows on each side of the caeon(sic). Two crows flew down near him and the youth listened to hear what was the matter.

The two crows cried out, “Somebody says. Somebody says.”

The youth did not know what to make of this.

A crow on the opposite side called out, “What is the matter? Tell us! Tell us! What is wrong?”

The first two cried out, “Two of us got killed. We met two of our men who told us.”

Then they told the crows how two men who were out hunting killed twelve deer, and a party of the Crow People went to the deer after they were shot. They said, “Two of us who went after the blood of the deer were shot.”

The crows on the other side of the caeon (sic) called, “Which men got killed?”

“The chaparral cock, who sat on the horn of the deer, and the crow who sat on its backbone.”

The others called out, “We are not surprised they were killed. That is what we tell you all the time. If you go after dead deer you must expect to be killed.”

“We will not think of them longer,” so the two crows replied. “They are dead and gone. We are talking of things of long ago.”[7]

But the youth sat quietly below and listened to everything that was said.

After a while the crows on the other side of the canon made a great noise and began to dance. They had many songs at that time. The youth listened all the time. After the dance a great fire was made and he could see black objects moving, but he could not distinguish any people. He recognized the voice of Hasjelti.[8] He remembered everything in his heart. He even remembered the words of the songs that continued all night. He remembered every word of every song. He said to himself, “I will listen until daylight.”

The Crow People did not remain on the side of the canon where the fires were first built. They crossed and recrossed the canon in their dance. They danced back and forth until daylight. Then all the crows and the other birds flew away to the west. All that was left was the fires and the smoke.

Then the youth started for his brothers’ camp. They saw him coming. They said, “He will have lots of stories to tell. He will say he saw something no one ever saw.”

But the brother-in-law who was with them said, “Let him alone. When he comes into camp he will tell us all. I believe these things do happen for he could not make up these things all the time.”

Now the camp was surrounded by pinon brush and a large fire was burning in the centre. There was much meat roasting over the fire. When the youth reached the camp, he raked over the coals and said. “I feel cold.”

Brother-in-law replied, “It is cold. When people camp together, they tell stories to one another in the morning. We have told ours, now you tell yours.”

The youth said, “Where I stopped last night was the worst camp I ever had.” The brothers paid no attention but the brother-in-law listened.

The youth said, “I never heard such a noise.” Then he told his story. Brother-in-law asked what kind of people made the noise.

The youth said, “I do not know. They were strange people to me, but they danced all night back and forth across the canon and I heard them say my brothers killed twelve deer and afterwards killed two of their people who went for the blood of the deer. I heard them say, ‘That is what must be expected. If you go to such places, you must expect to be killed.'”

The elder brother began thinking. He said, “How many deer did you say were killed?”

“Twelve.”

Elder brother said, “I never believed you before, but this story I do believe. How do you find out all these things? What is the matter with you that you know them?”

The boy said, “I do not know. They come into my mind and to my eyes.”

Then they started homeward, carrying the meat. The youth helped them.

As they were descending a mesa, they sat down on the edge to rest. Far down the mesa were four mountain sheep. The brothers told the youth to kill one.

The youth hid in the sage brush and when the sheep came directly toward him, he aimed his arrow at them. But his arm stiffened and became dead. The sheep passed by.

He headed them off again by hiding in the stalks of a large yucca. The sheep passed within five steps of him, but again his arm stiffened as he drew the bow.

Mythical Sand Painting of the Navajo Indians by James Stevenson (2006)[9]

He followed the sheep and got ahead of them and hid behind a birch tree in bloom. He had his bow ready, but as they neared him they became gods. The first was Hasjelti, the second was Hostjoghon,[10] the third Naaskiddi,[11] and the fourth Hadatchishi.[12] Then the youth fell senseless to the ground.

The four gods stood one on each side of him,[13] each with a rattle.[14] They traced with their rattles in the sand the figure of a man, drawing lines at his head and feet. Then the youth recovered and the gods again became sheep. They said, “Why did you try to shoot us? You see you are one of us.” For the youth had become a sheep.

The gods said, “There is to be a dance, far off to the north beyond the Ute Mountain. We want you to go with us. We will dress you like ourselves and teach you to dance. Then we will wander over the world.”

Now the brothers watched from the top of the mesa but they could not see what the trouble was. They saw the youth lying on the ground, but when they reached the place, all the sheep were gone. They began crying, saying, “For a long time we would not believe him, and now he has gone off with the sheep.”

They tried to head off the sheep, but failed. They said, “If we had believed him, he would not have gone off with the sheep. But perhaps some day we will see him again.”

At the dance, the five sheep found seven others. This made their number twelve. They journeyed all around the world. All people let them see their dances and learn their songs. Then the eleven talked together and said,

“There is no use keeping this youth with us longer. He has learned everything. He may as well go back to his people and teach them to do as we do.”

So the youth was taught to have twelve in the dance, six gods and six goddesses, with Hasjelti to lead them. He was told to have his people make masks to represent the gods.

So the youth returned to his brothers, carrying with him all songs, all medicines, and clothing.

JUDSON, KATHARINE BERRY., ED. MYTHS AND LEGENDS OF CALIFORNIA AND THE OLD SOUTHWEST. MYTHS AND LEGENDS OF CALIFORNIA AND THE OLD SOUTHWEST BY VARIOUS. PLACE OF PUBLICATION NOT IDENTIFIED: A.C. MCCLURG & CO., 1912. HTTPS://WWW.GUTENBERG.ORG/FILES/2503/2503-H/2503-H.HTM#LINK2H_4_0057.

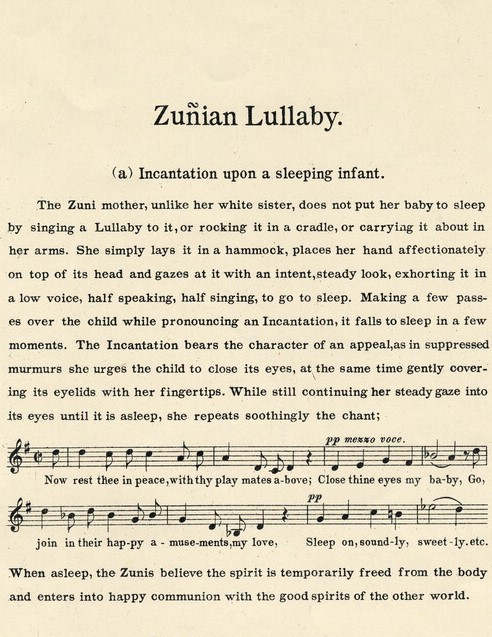

[1] This image depicts all Diné deities that appear in this story. A more complete description is above the picture in the original.

[2] The proper name for this tribe is Diné. The name Navajo comes from a Spanish adaptation of the Tewa Pueblo word navahu’u, meaning “fields adjoining an arroyo.” (OED)

[3] Likely an attempted spelling of Tódich’ii’nii (Bitter Water clan)

[4] Every Navajo belongs to four clans, the first is from the mother, the second from the father, the third is from the maternal grandfather and the fourth is from the paternal grandfather. These clans are used to define complex familial and social relationships.

[5] Likely a reference to the Four Sacred Mountains that define the traditional Diné homeland.

[6] Roadrunner (OED)

[7] Diné customs regarding death are complex.

[8] Likely an attempted spelling of Haashchʼééłtiʼí, the Talking God.

[10] Mask 5 represents Haashchʼééłtiʼí (Hasjelti). Mask 6 represents Haashchʼééʼooghaan (Hostjoghon).

[11] Likely an attempted spelling of Haashchʼééʼooghaan, the Calling God.

[12] I could find little information on this/these deity(s). In 2006, James Stevenson wrote, “The Naaskiddi are hunchbacks; they have clouds upon their backs, in which seeds of all vegetation are held.” They are depicted in sand paintings as carrying staffs of lightning.

[13] It is unclear which deity is referenced here. I could only find this spelling in other versions of this story.

[14] Some tellings state where each deity stood for this ritual.

[15] Ceremonial rattles are integral in Diné rituals.

Contexts

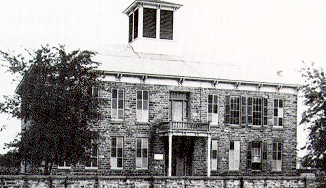

Stories such as this one were nearly lost due to the widespread use of residential schools to educate young Native Americans. These schools banned the use of their first language, stories from their culture, and traditional clothing- and hairstyles. These schools, like The Carlisle Indian Industrial School, were based on the philosophy of “Kill the Indian, save the man“.

Because of these schools, a whole generation lost much of their cultural identity, through the language, art, and stories of their people.

Resources for Further Study

- “The Sacred Hoop: A Contemporary Perspective on Native American Literature” from The Sacred Hoop: Recovering the Feminine in American Indian Traditions by Paula Gunn Allen is a great essay on how to read Native Literature as a non-Native.

- “Ceremonial of Hasjelti Daljis and Mythical Sand Painting of the Navajo Indians” by James Stevenson provides interesting insights and observations into Navajo ceremonies and deities.

- “Mortuary Customs of the Navajo Indians” by R. W. Shuffeldt gives an account of the complexity of death in Diné culture.

- “Diné-Anaasází Relations, Clans, and Ethnogenesis” from A Diné History of Navajoland by Klara Kelley and Harris Francis gives a more in-depth view of the Diné clan system.

- “Collaboration and Indian Education: Exploring Intergovernmental Partnerships between Tribes and Public Schools” by Thaddieus W. Conner looks at the impact of residential schools.

Pedagogy

This story lends itself to comparative reading of similar stories from other cultures. For instance, the bringing of knowledge and civilization bears resemblance to the myth of Prometheus and the idea of a mortal becomeing a god is similar to the story of Heracles/Hercules.

Contemporary Connections

- This story has interesting similarities to the story of Joseph from Genesis 37 & 39-47.

- The clan system is still important to contemporary Diné.

- The Four Sacred Mountains continue to saturate Navajo culture.