American Animals Part II: The Buffalo

By Jacob Abbott

Annotations by Josh BEnjamin

We gave two weeks since an article on the Beaver, his habits, &c. The second in the series is a sketch of the Buffalo. The article is long, but very interesting:

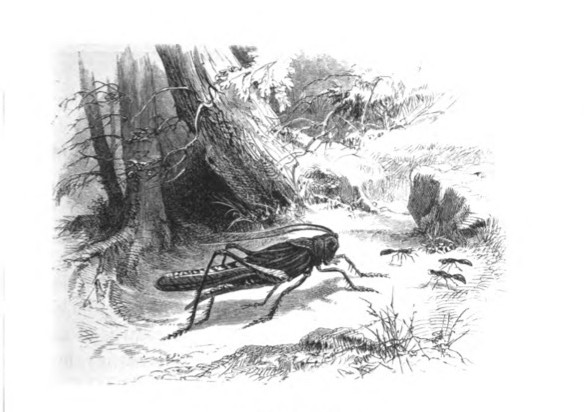

The buffalo, or bison, is a sort of wild bull, with a monstrous, shaggy head and ferocious aspect. They are gregarious animals, that is, they live and feed together in immense herds. Almost all animals that feed on grass and herbage are gregarious, while beasts of prey are generally solitary in their habits. It is necessary for them to be so, for in order to succeed in their hunting, they must prowl alone, or watch in ambush, patiently and in silence, for their prey. There are some exceptions, as in the case of wolves, for example, which usually hunt together in packs. There is a reason for this exception, too, for the wolves live generally by killing and devouring animals larger than themselves, and so are obliged to combine their strength in order to overpower their prey.

The buffalos are gregarious by habit in order that they may the better defend themselves from their enemies; and so abundant is the food furnished for them by the luxuriant grass of the prairies, and so boundless is the extent of the plains over which they roam, that the herds increase to an almost incredible extent. Travellers sometimes find the whole region black with them in every direction as far as they can see. In one case that is described, the country was covered with a herd, or an aggregation of herds, so vast that the party journeying were six days in passing through them. The aspect which they presented with five, ten, and sometimes twenty thousand in sight at a time, spreading in every direction over the plains, some bellowing, some fighting, others advancing defiantly toward their supposed foes, and tearing up the soil with their hoofs and horns—the earth trembling under their tramp, and the air filled with a prolonged and portentous murmur, presented to the view of the traveller a really appalling spectacle.

The bellowing of a large herd is sometimes heard at a distance of two miles!

Of course the frosts and snows coming down from the Arctic regions in winter bind up arid cover large tracts of land which in summer are clothed with luxuriant herbage. The grazing animals, accordingly, move northward to great distances as the season changes.

The country being intersected by rivers and streams in every part, would seem to interpose great difficulties in the way of the passage of the animals to and fro. The herd, on approaching a river, if it is fordable, descend the bank in a massive column, and wade or swim across. If the descent of the bank is not already gradual, it soon becomes so by the trampling of so many heavy hoofs, the most daring, of course, impelled partly by their courage, and partly by the pressure from behind, going down first and breaking the way.

If there are calves in the herd, and the bank remains so steep that they dare not go down, their mothers always wait with them upon the margin in great apparent distress, and make every effort to encourage them to go down. Sometimes it is said that the calves contrive to get upon the backs of the cows, and are conveyed in that way across the stream.

It not unfrequently happens that the landing proves not to be good when the animals arrive on the further side, so that instead of a hard beach by which to ascend to the level of the plain, they find themselves sinking into quicksands or mire. The scene which is witnessed in a case like this, presents sometimes, it is said, an aspect almost awful. The older and stronger beasts are perhaps able, after long-continued and desperate struggles, in which they trample down and climb over the others in their excitement and terror, to regain their footing and clamber up the bank; but often many are unable to extricate themselves, and perish miserably—their bodies being borne away by the current down the stream.

The case is still worse sometimes when the river is frozen, and the herd is consequently compelled to cross upon the ice. The animals have no means of judging of the strength of the ice except by taking the opinion of the leaders, who go down cautiously, and step in a timid, hesitating manner upon the margin of it, and then if it gives no sign of weakness under the weight of a single tread, they conclude it to be strong, and proceed. But it may be strong enough to bear one, while far too weak to sustain the weight of a hundred.

Still the whole herd follow on, and perhaps when the head of the column has advanced toward the middle of the stream, some cracking sound, or other token of weakness, gives the alarm. The leaders stop, the others press on, the ice becomes immensely overloaded, and presently goes down with a great crash, carrying hundreds into the water. Then ensues a scene of struggling, and commotion, and terror impossible to describe. Animals of every age and size are writhing and plunging in the water, vainly trying to climb up upon cakes of ice, or to force their way through the floating fragments to the shore—bellowing all the time with terror. Some at last gain the bank, but others are swept away in great numbers beneath the unbroken ice below, and drowned.

In making their journeys the buffalos move in columns, those behind keeping in the track of those before, and in this way they make trails which soon become well worn; and being pretty wide, on account of the columns being formed with several animals abreast, they look like wagon roads. These roads extend, in some places, for hundreds of miles across the country. When they are once made, they are followed year after year by successive herds. In this respect the habits of the buffalo correspond with those of domestic cows in the pastures of New England, who lay out paths on the hillsides and in the woods, and continue to use them, when they are once worn, for many years.

The buffalo, as may readily be supposed, was a great resource to the Indians. His flesh furnished him with an abundant supply of excellent food. His skin served for cloth, and, when cut into thongs, for cords. His horns were made into vessels and implements of various kinds. Some tribes also made boats of his hide by stretching it, when green, over a frame made of a suitable form for the purpose intended. This, of course, was a very clumsy sort of craft, but being made without any seam, was perfectly water-tight and very serviceable.

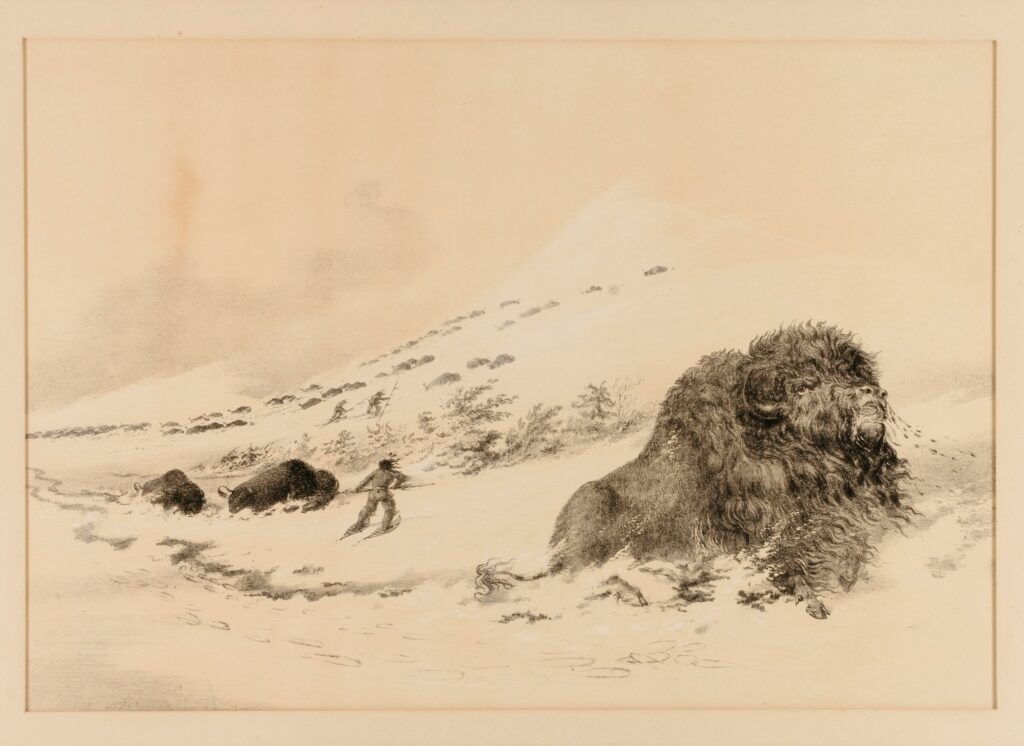

The buffalo has many enemies, but the greatest of all is civilized man. So long as the vast herds were attacked only by bears, packs of wolves, and Indians armed simply with spears and arrows, they were able to hold their ground. The bulls of the herd, with their prodigious strength, and the formidable weapons with which nature has provided them in their horns, would maintain terrible conflicts with any of these foes, and would often come off victorious from the fight. But when the white man came, mounted upon a horse and armed with a rifle, no choice was left to him but to abandon the field; and in proportion as the tide of emigration moves toward the west, the buffalo retires before it; and will probably in time entirely disappear.

The frontiers, however, of his old dominion are drawn in very slowly and reluctantly, so that even the steamboat sometimes overtakes him. Cases have occurred in which steamboats, in feeling their way up some of the western branches of the Mississippi and Missouri, have come upon a herd of buffalos crossing the stream, and the poor beasts, in the midst of their amazement at the spectacle, have been shot by the rifles of the passengers from the deck.

There is one case mentioned in which a steamboat passed so near a buffalo swimming in the water that a passenger on board, who had learned the use of the lasso in South America, threw a rope, with a slip noose at the end, through the air and caught him by the horns. The crew then pulled the poor beast alongside of the steamer, and, getting slings under him, hoisted him on board and butchered him for his beef.

Gallery, Washington, D.C.

Abbott, JAcob. “American Animals.” Youth’s companion 35, No. 24 (June 1861): 100.

Contexts

Youth’s Companion excerpted this selection from Jacob Abbott’s longer work, American History Volume I: Aboriginal America, published in 1860 as an illustrated book with ten chapters: “Types of Life in America,” “Face of the Country,” “Remarkable Plants,” “Remarkable Animals,” “The Indian Races,” “The Indian Family,” “Mechanic Arts,” “Indian Legends and Tales,” “Constitution and Character of the Indian Mind,” and “The Coming of the Europeans.” Abbott intended his series to be a complete overview of American history that began with the geography, flora and fauna, and indigenous people as indicative of the “earliest periods” of the country. Several more volumes followed, titled Discovery of America, The Southern Colonies, The Northern Colonies, Wars of the Colonies, Revolt of the Colonies, War of the Revolution, and Washington.

Abbott’s introduction reads:

“IT is the design of this work to narrate, in a clear, simple, and intelligible manner, the leading events connected with the history of our country, from the earliest periods, down, as nearly as practicable, to the present time. The several volumes will be illustrated with all necessary maps and with numerous engravings, and the work is intended to comprise, in a distinct and connected narrative, all that it is essential for the general reader to understand in respect to the subject of it, while for those who have time for more extended studies, it may serve as an introduction to other and more copious sources of information.

The author hopes also that the work may be found useful to the young, in awakening in their minds an interest in the history of their country, and a desire for further instruction in respect to it. While it is doubtless true that such a subject can be really grasped only by minds in some degree mature, still the author believes that many young persons, especially such as are intelligent and thoughtful in disposition and character, may derive both entertainment and instruction from a perusal of these pages.”

Mistakenly called buffalo, the American Bison once roamed across North America in large numbers. Though we may never know how many bison were alive at their peak, experts believe they once numbered between 30 and 75 million. By 1800, the herds east of the Mississippi were killed off. By 1838, many herds in the northern and southern portions of the Great Plains were destroyed. There were only 300 wild bison by the turn of the 20th century. In 1894, Congress passed a law making it illegal to hunt bison in Yellowstone National Park. Twenty-one bison were purchased in 1902 to rebuild the Yellowstone herd. In 2019, the Yellowstone herd numbered nearly 5,000, and there were nearly 40,000 bison across North America.

Definitions from Oxford English Dictionary

aggregation: A whole composed of many individuals; a mass formed by the union of distinct particles; a gathering, assemblage, collection.

gregarious: Of classes or species of animals: Living in flocks or communities, given to association with others of the same species.

herbage: Herbs collectively; herbaceous growth or vegetation; usually applied to grass and other low-growing plants covering a large extent of ground, esp. as used for pasture.

prodigious: That causes wonder or amazement; marvelous, astonishing. Also in an unfavorable sense: appalling.

Resources for Further Study

- The full text of Abbott’s book is available at the Internet Archive.

- Abbott was a prolific writer of children’s books, including his popular series centered around the Rollo character, which he intended as entertainment, language practice, and examples of reason and morality.

- The U.S. Department of the Interior has some facts about the American Bison, named the U.S. national mammal in 2016.

Contemporary Connections

The National Park Service has information on bison conservation, as does Bison Range Restoration, which is in the process of transitioning oversight of the National Bison Range from U.S. Fish and Wildlife to resource managers from the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes (CKST). The National Wildlife Federation is also involved in ongoing efforts to return bison to tribal lands.

There are several works of fiction regarding the Native American connection to the American Bison:

- Buffalo Dreams by Kim Doner links the traditional connection to buffalo to the present day.

- Buffalo Song by Joseph Bruchac (Abenaki) is a buffalo history: how they came to be, why they were almost killed off, and how Great Plains Natives still see them as sacred.