The Mission of the Flowers

By Frances E. Watkins

Annotations by Rene Marzuk

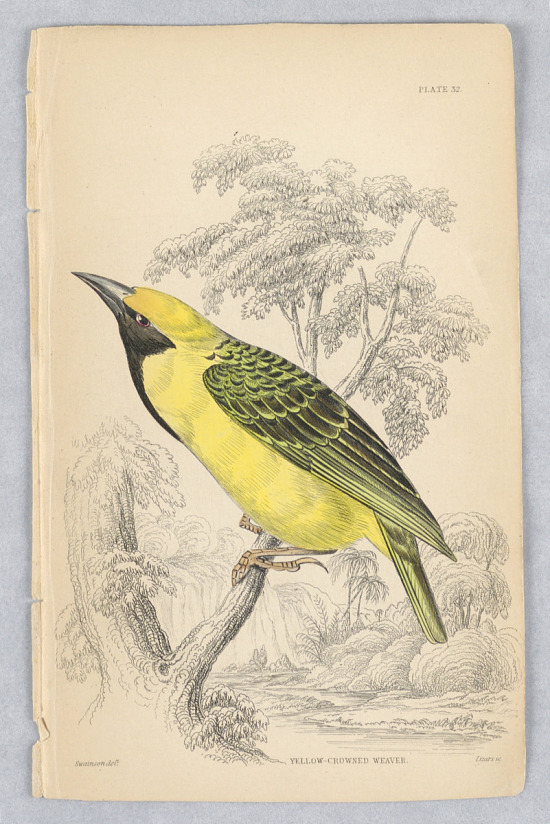

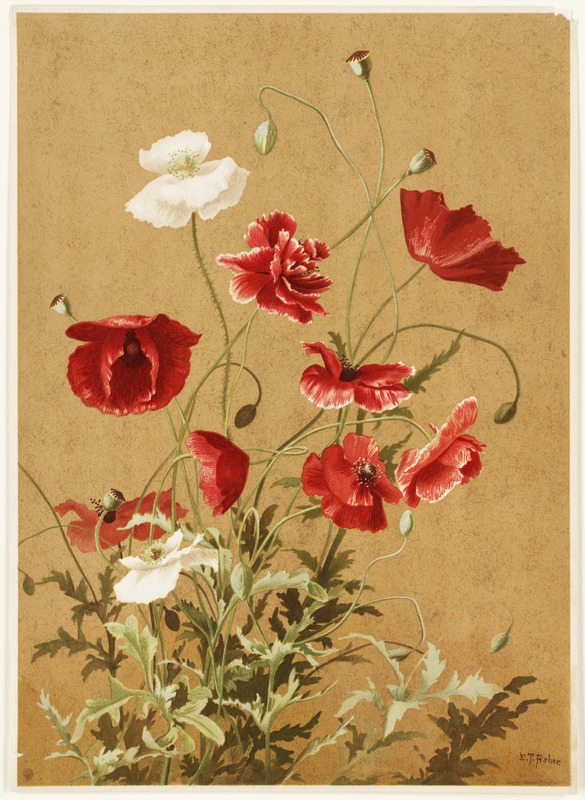

In a lovely garden filled with fair and blooming flowers stood a beautiful rose tree.[1] It was the centre of attraction and won the admiration of every eye; its beauteous flowers were sought to adorn the bridal wreath and deck the funeral bier. It was a thing of joy and beauty, and its earth mission was a blessing. Kind hands plucked its flowers to gladden the chamber of sickness and adorn the prisoner’s lonely cell. Young girls wore them ’mid their clustering curls, and grave brows relaxed when they gazed upon their wondrous beauty.—Now the rose was very kind and generous hearted, and seeing how much joy she dispensed wished that every flower could only be a rose and like herself have the privilege of giving joy to the children of men; and while she thus mused a bright and lovely spirit approached her and said, “I know thy wishes and will grant thy desires.—Thou shall have power to change every flower in the garden to thine own likeness. When the soft winds come wooing thy fairest buds and flowers, thou shalt breathe gently on thy sister plants, and beneath thy influence they shall change to beautiful roses.” The rose tree bowed her head in silent gratitude to the gentle being who had granted her this wondrous power. All night the stars bent over her from their holy homes above, but she scarcely heeded their vigils. The gentle dews nestled in her arms and kissed the cheeks of her daughters; but she hardly noticed them;—she was waiting for the soft airs to awaken and seek her charming abode. At length the gentle airs greeted her and she hailed them with a joyous welcome, and then commenced her work of change. The first object that met her vision was a tulip superbly arrayed in scarlet and gold. When she was aware of the intention

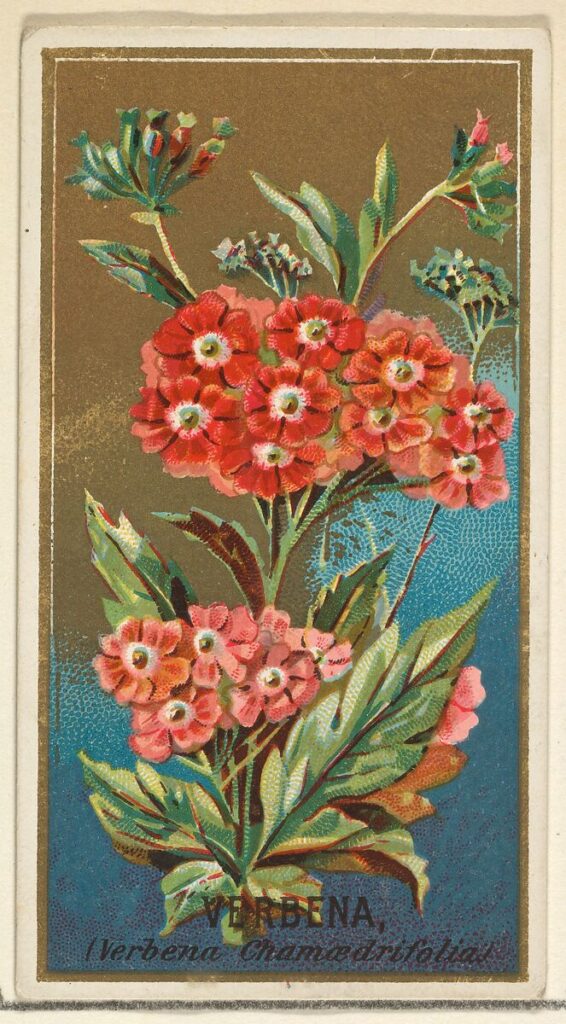

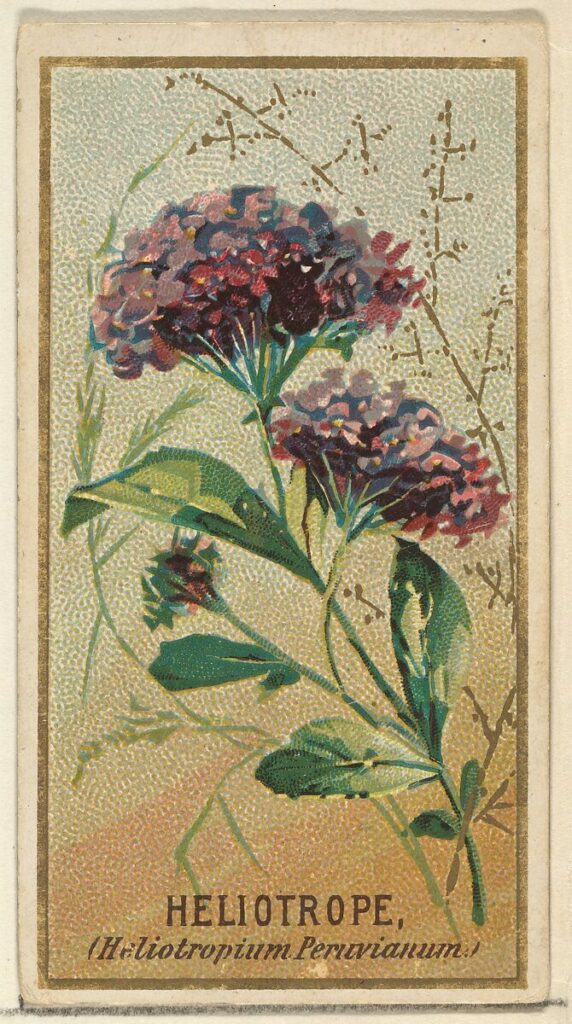

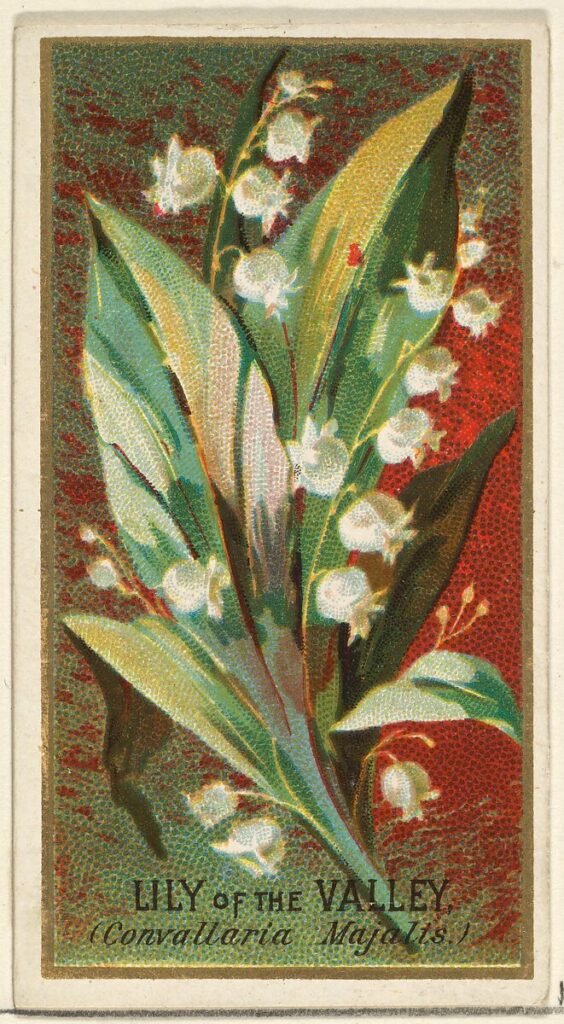

of her neighbor her cheeks flamed with anger, her eyes flashed indignantly, and she haughtily refused to change her proud robes for the garb the rose tree had prepared for her, but she could not resist the spell that was upon her. And she passively permitted the garments of the rose to enfold her yielding limbs.—The verbenas saw the change that had fallen upon the tulip, and dreading that a similar fate awaited them crept closely to the ground, and while tears gathered in their eyes, they felt a change pass through their sensitive frames, and instead of gentle verbenas they were blushing roses. She breathed upon the sleepy poppies; a deeper slumber fell upon their senses, and when they awoke, they too had changed to bright and beautiful roses. The heliotrope read her fate in the lot of her sisters, and bowing her fair head in silent sorrow, gracefully submitted to her unwelcome destiny. The violets, whose mission was to herald the approach, were averse to losing their individuality. Surely, said they, we have a mission as well as the rose;

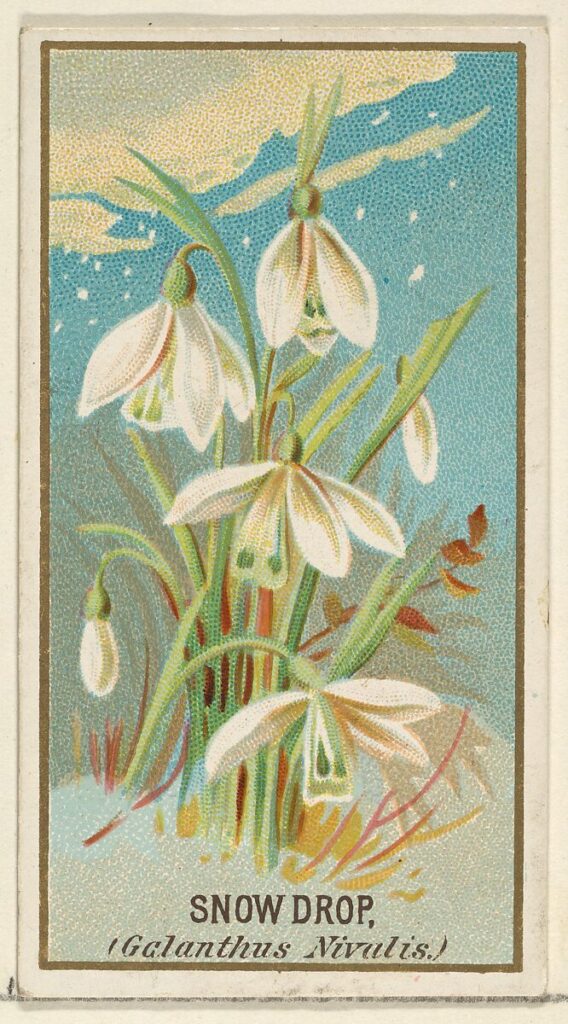

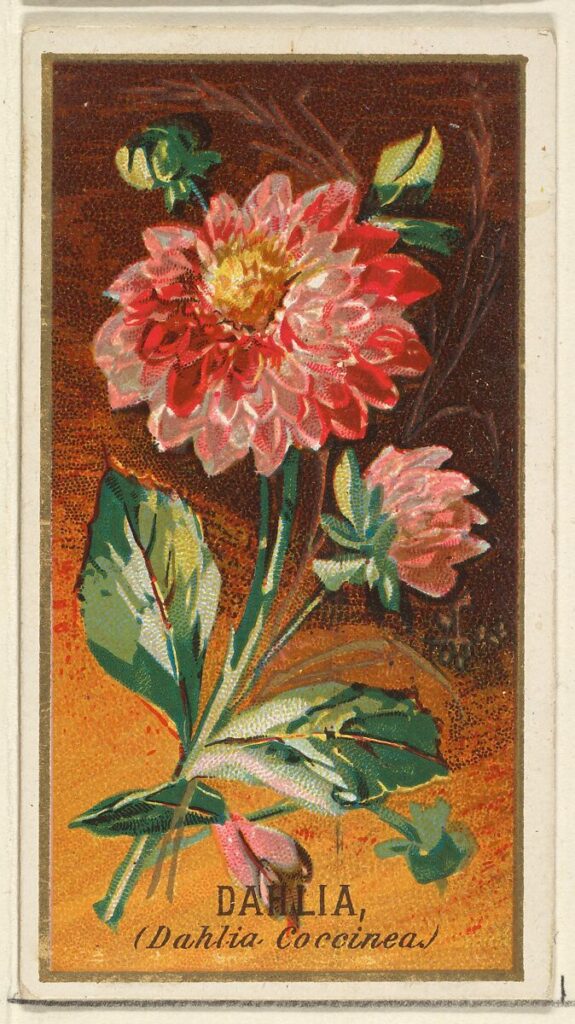

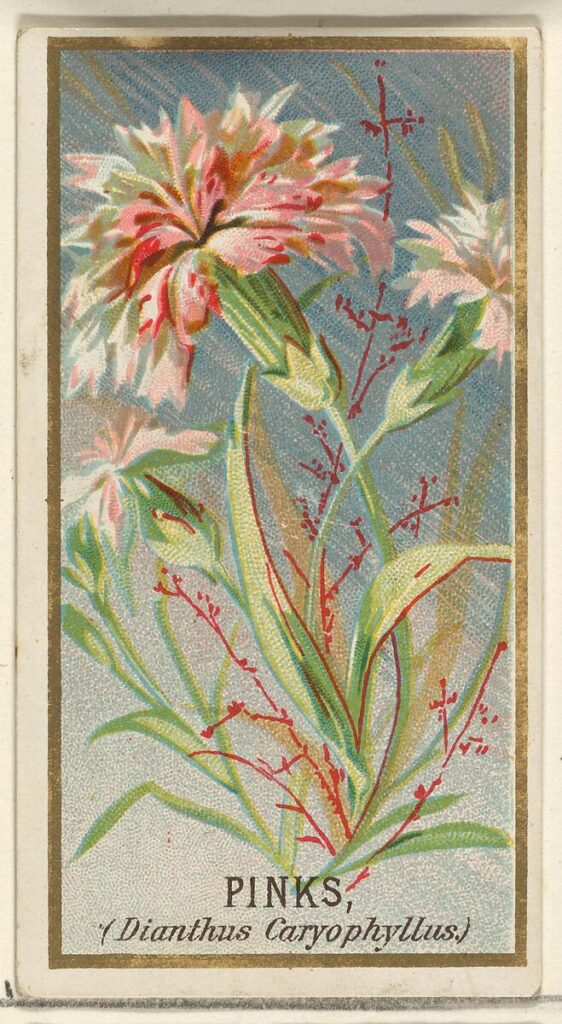

but with heavy hearts they saw themselves changed like their sister plants. The snow drop drew around her her robes of virgin white; she would not willingly exchange them for the most brilliant attire that ever decked a flower’s form; to her they were the emblems of purity and innocence; but the rose tree breathed upon her, and with a bitter sob she reluctantly consented to the change. The dahlias lifted their heads proudly and defiantly; they dreaded the change but scorned submission; they loved the fading year, and wished to spread around his dying couch their brightest, fairest flowers; but vainly they struggled, the doom was upon them, and they could not escape. A modest lily that grew near the rose tree shrank instinctively from her; but it was in vain, and with tearful eyes and trembling lips she yielded, while a quiver of agony convulsed her frame. The marygolds sighed submissively and made no remonstrance. The garden pinks grew careless and submitted without a murmur; while other flowers less fragrant or less

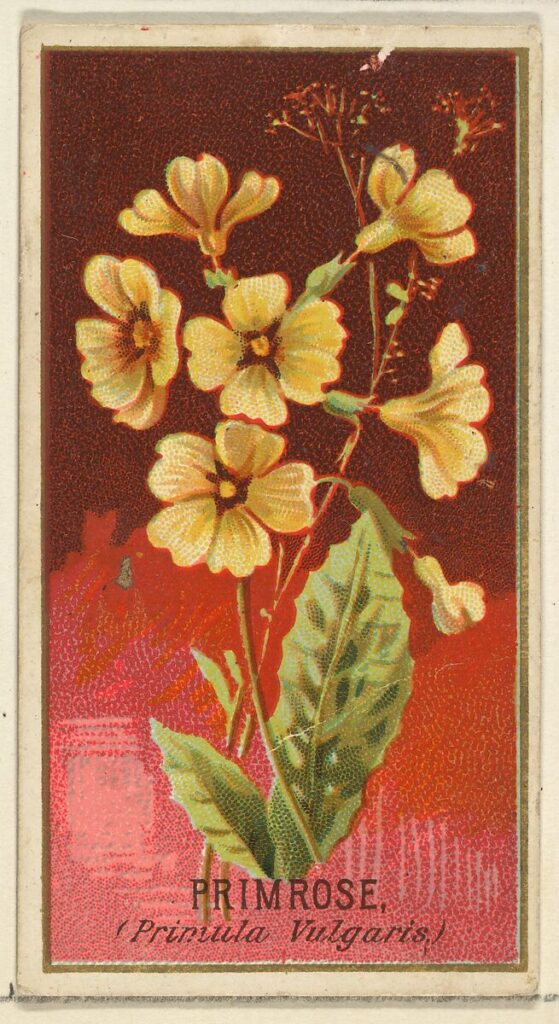

fair paled with sorrow or reddened with anger, but the spell of the rose tree was upon them and every flower was changed by her power, and that once beautiful garden was overrun with roses; it had become a perfect wilderness of roses; the garden had changed, but that variety which had lent it so much beauty was gone, and men grew tired of the roses, for they were everywhere. The smallest violet peeping faintly from its bed would have been welcome, the humblest primrose would have been hailed with delight;—even a dandelion would have been a harbinger of joy, and when the rose saw that the children of men were dissatisfied with the change

she had made, her heart grew sad within her, and she wished the power had never been given her to change her sister plants to roses, and tears come into her eyes as she mused, when suddenly a rough wind shook her drooping form and she opened her eyes and found that she had only been dreaming. But an important lessons had been taught; she had learned to respect the individuality of her sister flowers and began to see that they, as well as herself, had their own missions,—some to gladden the eye with their loveliness and thrill the soul with delight; some to transmit fragrance to the air; others to breathe a refining influence upon the world; some had power to lull the aching brow and soothe the weary heart and brain into forgetfulness, and of those whose mission she did not understand she wisely concluded there must be some object in their creation, and resolved to be true to her own earth mission and lay her fairest buds and flowers upon the altars of love and truth.

WATKINS, FRANCES E. “THE MISSION OF THE FLOWERS.” REPOSITORY OF RELIGION AND LITERATURE, AND OF SCIENCE AND ART’S VOL. III, NO. 1 (JANUARY 1860): 26-8.

[1] A Tree Rose or Rose Standard is not a rose variety, but the result of grafting a regular rose plant onto a trunk to achieve the appearance of a tree.

Contexts

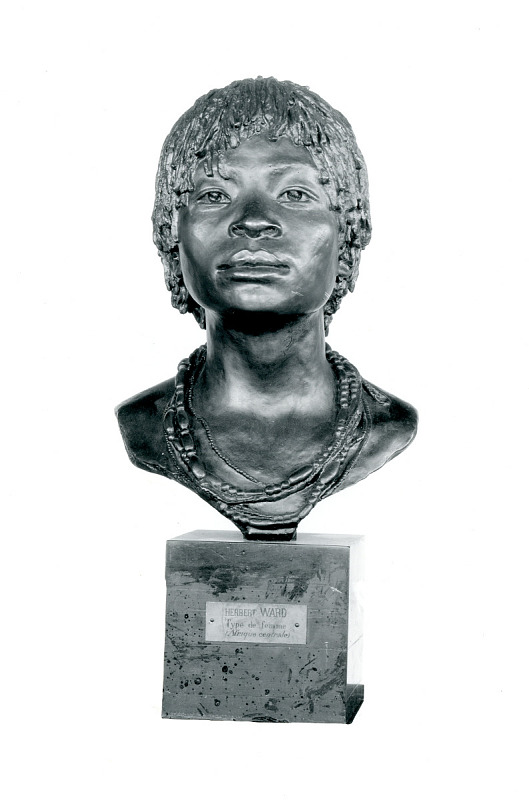

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (1825-1911) was an African American public speaker, poet, teacher, and social activist. As a public intellectual, she advocated for antislavery, education, and temperance. Her short story “The Two Offers,” which appeared in 1859 in consecutive issues of The Anglo-African Magazine, is the first short story published by an African American writer in the United States.

The Repository of Religion and Literature, and of Science and Arts was a short-lived (1858-63) quarterly for Black children published by a group of African Methodist Episcopal (AME) societies.

Definitions from Oxford English Dictionary:

emblem: A picture of an object (or the object itself) serving as a symbolical representation of an abstract quality, an action, state of things, class of persons, etc.

beauteous: Highly pleasing to the senses, esp. the sight; beautiful; (also, in recent use) sensuously alluring, voluptuous. Chiefly literary.

bier: The movable stand on which a corpse, whether in a coffin or not, is placed before burial; that on which it is carried to the grave.

vigil: An occasion or period of keeping awake for some special reason or purpose; a watch kept during the natural time for sleep.

Resources for Further Study

- Tabitha Lowery’s scholarly essay “‘Thank God for Little Children’: The Reception History of Frances E. W. Harper’s Children’s Poetry,” included in volume 67, number 2, of ESQ: A Journal of Nineteenth-Century American Literature and Culture (2021).

- The house where Frances Ellen Watkins Harper lived in Philadelphia, PA, from 1870 until 1911 is a National Historic Landmark.

- Ian Zack’s article “Overlooked No More: Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, Poet and Suffragist,” appeared on February 7th, 2023 in The New York Times.

Contemporary Connections

“How to Increase Biodiversity in Your Backyard and Garden,” from the Dogwood Alliance’s website.