Vegetable Clothing

By C. J. Russell

Annotations by Mary Miller/KK

by D.C. Beard from St. Nicholas Magazine, 13, no. 2

May – October 1886), 524.

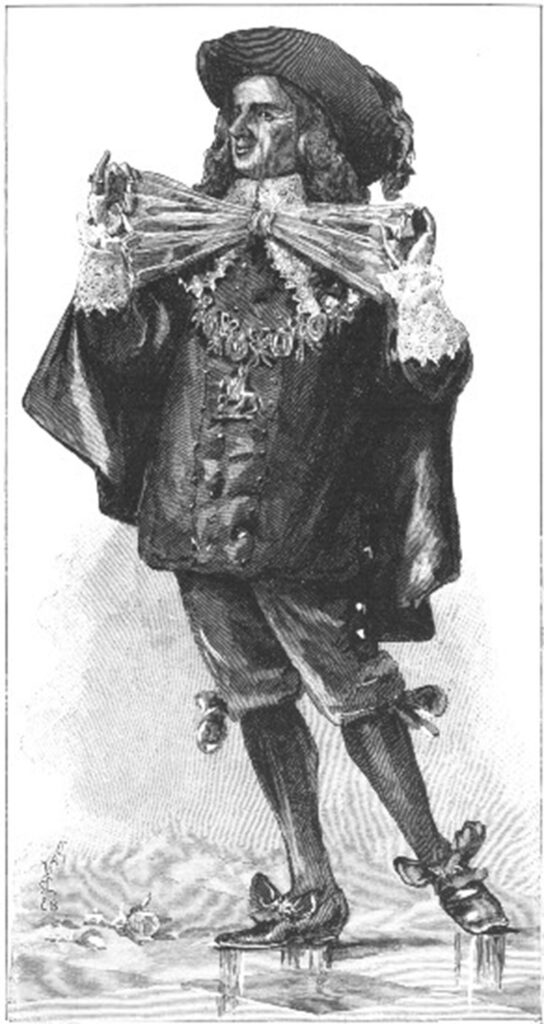

About two hundred years ago the governor of the island of Jamaica, Sir Thomas Lynch, sent to King Charles II. of England a vegetable necktie, and a very good necktie it was, although it had grown on a tree and had not been altered since it was taken from the tree. It was as soft and white and delicate as lace, and it is not surprising that the King should have expressed his doubts when he was told that the beautiful fabric had grown on a tree in almost the exact condition in which he saw it. It had been stretched a little, and that was all.

But if King Charles was astonished to learn that neckties grew on trees in Jamaica, what must have been the feelings of a stranger traveling in Central America, on being told that mosquito-nets grew on trees in that country? He had complained to his host that the mosquitoes had nearly eaten him up the night before, and had been told in response that he should have a new netting put over his bed.

Satisfied with this statement, the traveler was turning away, but his attention was arrested by his host’s calmly continuing, “in fact, we are going to strip a tree anyhow, because there is to be a wedding on the estate, and we wish to have a dress ready for the bride.”

“You don’t mean,” said the traveler incredulously, “that mosquito-netting and bridal dresses grow on trees, do you?”

“That is just what I mean,” replied his host.

“All right,” said the stranger, who fancied a joke was being attempted at his expense, “let me see you gather the fruit and I will believe you.”

“Certainly,” was the answer; “follow the men, and you will see that I speak the exact truth.”

Still looking for some jest, the stranger followed the two men who were to pluck the singular fruit, and stood by when they stopped at a rather small tree, bearing thick, glossy-green leaves, but nothing else which the utmost effort of the imagination could convert into the netting or the wedding garments. The tree was about twenty feet high and six inches in diameter, and its bark looked much like that of a birch-tree.

“Is this the tree?” asked the stranger.

“Yes, señor,” answered one of the men, with a smile.

“I don’t see the mosquito-netting nor the wedding-dress,” said the stranger, “and I can’t see any joke either.”

“If the señor will wait a few minutes he will see all that was promised, and more too,” was the reply. “He will see that this tree can bear not only mosquito-netting and wedding-dresses, but fish-nets and neck-scarfs, mourning crape [1] or bridal veils.”

The tree was without more ado cut down. Three strips of bark, each about six inches wide and eight feet long, were taken from the trunk and thrown into a stream of water. Then each man took a strip while it was still in the water, and with the point of his knife separated a thin layer of the inner bark from one end of the strip. This layer was then taken in the fingers and gently pulled, whereupon it came away in an even sheet of the entire width and length of the strip of bark. Twelve sheets were thus taken from each strip of bark, and thrown into the water.

A light broke in upon the stranger’s mind. Without a doubt these strips were to be sewn together into one sheet. The plan seemed a good one and the fabric thus formed might do, he thought, if no better cloth could be had.

The men were not through yet, however, for when each strip of bark had yielded its twelve sheets, each sheet was taken from the water and gradually stretched sidewise. The spectator could hardly believe his eyes. The sheet broadened and broadened until from a close piece of material six inches wide, it became a filmy cloud of delicate lace, over three feet in width. The astonished gentleman was forced to confess that no human-made loom ever turned out lace which could surpass in snowy whiteness and gossamer-like delicacy that product of nature.

The natural lace is not so regular in formation as the material called illusion [2], so much worn by ladies in summer; but it is as soft and white, and will bear washing, which is not true of illusion. In Jamaica and Central America, this wonderful lace is put to all the uses mentioned by the native to our traveler, and to more uses besides. In fact, among the poorer people it supplies the place of manufactured cloth, which they can not afford to buy; and the wealthier classes do not by any means scorn it for ornamental use.

Long before the white man found his way to this part of the world, the Indians had known and used this vegetable cloth; so that what was so new and wonderful to King Charles and Governor Sir Thomas Lynch was an old story to the natives. Some time after King Charles received his vegetable necktie, Sir Hans Sloane, whose art-collection and library were the foundation of the British Museum, visited Jamaica. He described the tree fully, and was the first person who told the civilized world about it. The tree is commonly called the lace-bark tree. Its botanical name is Lagetto lintearia.

Wells, c.j. “vegetable clothing,” St. Nicholas Magazine 13, no. 2 (May – October 1886):524-25

Essex (Image No. 000491).

Kew (EBC 67770).

[1] A veil worn by grieving women in Victorian times. Crape was a matte silk gauze that had been crimped with heated rollers; dyed black; and stiffened with gum, starch, or glue.

[2] Illusion, also known as tulle, is a fine netting fabric made of nylon. Appearing delicate and sheer, it has enough strength to be gathered and made into a bridal veil.

Contexts

This story represents an unusual example of respect for indigenous knowledge, all the more remarkable as it was written during the height of Western Imperialism. Antigua’s history and culture is complex. Inhabited first by indigenous Siboney and, later, Arawak and Carib Indians, the island’s colonization by whites began when a group of English settlers arrived in 1632, inaugurating its development as a valuable sugar colony and trading port. In the seventeenth century, sugar cane became the biggest source of income for the British overlords, who used slaves and indentured servants to cultivate, harvest, and process the plant. Uniquely among British Caribbean colonies, when Britain abolished slavery in the empire in 1834, Antigua immediately instituted full emancipation. The island became an associated state of the British Commonwealth in 1967, gaining full independence in 1981.

Resources for Further Study

- Learn about the history of the Jamaican lace-bark tree, Lagetto lintearia.

- Read about the botanical economics of the lace-bark tree (password-protected).

- The history of the Caribbean Islands is a fascinating, and troubling, story of conquest, piracy, slavery, and the devastation of indigenous people and culture at the hand of Western imperialism. For a deeper dive, read From Columbus to Castro: The History of the Caribbean 1492-1969 by Eric Williams, who served as the first Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago from 1962 until his death in 1981.

Contemporary Connections

The lace-bark tree has been identified as a source for eco-friendly fabrics. See “Eco-fibres old and new” from the Kew Gardens webpage.

Jamaica Kincaid’s A Small Place is a native Antiguan’s acerbic address to tourists which likens current tourism to a new form of colonization, enslaving the locals and featuring environmental racism. The narrated version, read by Robin Miles, is delightful. Here is a small sample.

Monica Drake recounts her family’s visit to Antigua in “Jamaica Kincaid’s Antigua.”