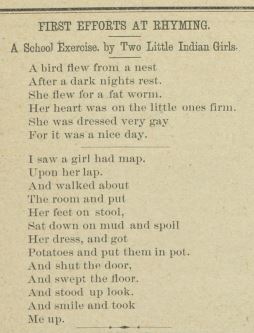

[First Efforts at Rhyming]

By “Two Little Indian Girls”

Annotations by jessica Cory

A bird flew from the nest After a dark night's rest. She flew for a fat worm. Her heart was on the little ones firm. She was dressed very gay For it was a nice day. I saw a girl had map. Upon her lap. And walked about The room and put Her feet on stool, Sat down on mud and spoil Her dress, and got Potatoes and put them in pot. And shut the door, And swept the floor. And stood up look. And smile and took Me up.

two little indian girls. “first efforts at rhyming.” The Morning Star, 4 no. 7 (Feb. 1884):4.

Contexts

The nonstandard punctuation and grammar present in the poem are likely due to its creation by students learning English as a second language. While this rhyme may seem cutesy, it’s important to realize that these words were likely written as an act of forced assimilation, as The Morning Star was published by The Carlisle Indian Industrial School, and the residential schools operating at the time forbade Native children to speak their own languages (among other assimilation techniques).

The loss of language from the legacy of boarding schools has had a lasting impact on Native communities throughout the U.S., Canada, and Australia, where they were commonly implemented. Native children sometimes lost the ability to communicate with members of their own communities or families, and often were unable to teach their own children the language that was stolen from them, and thus generational language loss occurred. Several Indigenous languages were declared “extinct” and many more nearly followed suit.

To combat this language loss, often-grassroots Indigenous language revitalization efforts have been made in many Native communities. These efforts include teaching classes in Indigenous languages, forming immersion schools for young learners, and even developing apps or YouTube channels. Not only does language revitalization helped keep the languages alive, it also allows Indigenous peoples to more deeply connect to their cultures.

Resources for Further Study

- If you’re interested in learning more about The Carlisle School, I offer several resources on another page.

- For a more personal account of what this language loss looks like and how it affects Native peoples, check out Emily Fox’s piece.

- Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages provides a thorough examination about the effects of forbidding a student from speaking their Native language, and mentions The Carlisle School in particular.

Pedagogy

- Facing History and Ourselves is a great resource to begin the conversation about residential schools and language loss. Its focus is Canada, but the lesson plan and questions could easily be tweaked for U.S. discussion.

- The National Museum of the American Indian discusses the government’s double standard in forbidding Native languages and then seeking the help of Navajo Code Talkers in WWII. There is also a tab with several lesson plans for grades 6-12 along with ample resources.

Contemporary Connections

There has been some discussion about the necessity to compensate Indigenous peoples who experienced language loss due to residential schools, but thus far, the U.S. has not taken such actions. Also, it’s important to remember that English is a foreign language on Turtle Island (a term used by some Indigenous peoples and activists to refer to North America).