Answer to Guess Whom

Author unknown

Annotations by Celia hawley

Did you suppose, Madam Water, that I should not find out who you were? The very noise and uproar you make about yourself, is so characteristic, that it betrays you. Your fondness for display is quite inexcusable. It is seldom you take a step without making all around you hear of it. For myself, I delight to work secretly; and it is only when I am enraged by our frivolous sister, the Wind, that I openly rise in my might, and terrify the world.

You talk, as if you one had claims to majesty and beauty, but yourself. You never visited me in my deep, glowing, palaces, under Vesuvius and Ӕtna,—how then can you judge of my splendour? Travellers come from all parts of the world to look at my flaming brow, as I rise from the mountains, and make the earth quake around me; ask them if there is not beauty as well as sublimity in my upward motion? Iceland is my favourite retreat. Some say my father is buried there, and that he still heaves the island, by blowing his coals and working at his anvil. That is all a fable; but I love to stay there, just to show you how little I care for the most freezing reception you can give me. In that cold, northern region, wrapped up in your stiff dignity, it amuses me to see how quick you spit forth your indignation in boiling geysers, whenever I breathe upon you. If I were you, I would cultivate a better temper, before I boasted of my placid face, and a figure as flexile as the sister Graces. I regret being employed in such drudgery by man, as well as you; especially as we are generally obliged to do their work by fighting together.

I love to caper on Vesuvius; to gallop about among the clouds; to roar and roll under the islands, sometimes throwing them out of the ocean, from the hollow of my burning hand, and sometimes dragging them down to my caverns, with a might that makes the world tremble; but I do not love to struggle with you, in the slavery of distilleries and steam-boats.

But though lordly man forces all the elements into his use, he cannot prevent their sometimes rising beyond his power. When we do o’ermaster him I think you are about as much to be dreaded as I am. If you again are to claim superiority to me in that, or any other respect, I shall be as mad as

Fire.

Author Unknown. “Answer to guess whom.” The Juvenile Miscellany 4, no. 3 (July 1828): 367-69.

Contexts

To Americans in the 1930s, Mexico represented an ancient and deeply spiritual civilization much different than their own industrial one. Artists and writers visited and returned excited by the myths and rituals that permeated the everyday lives of Mexican people. Marsden Hartley, whose painting begins this page, made the trip in 1932 and returned interested in Aztec art’s landscapes and surviving remnants, as explained by the Smithsonian’s gallery label.

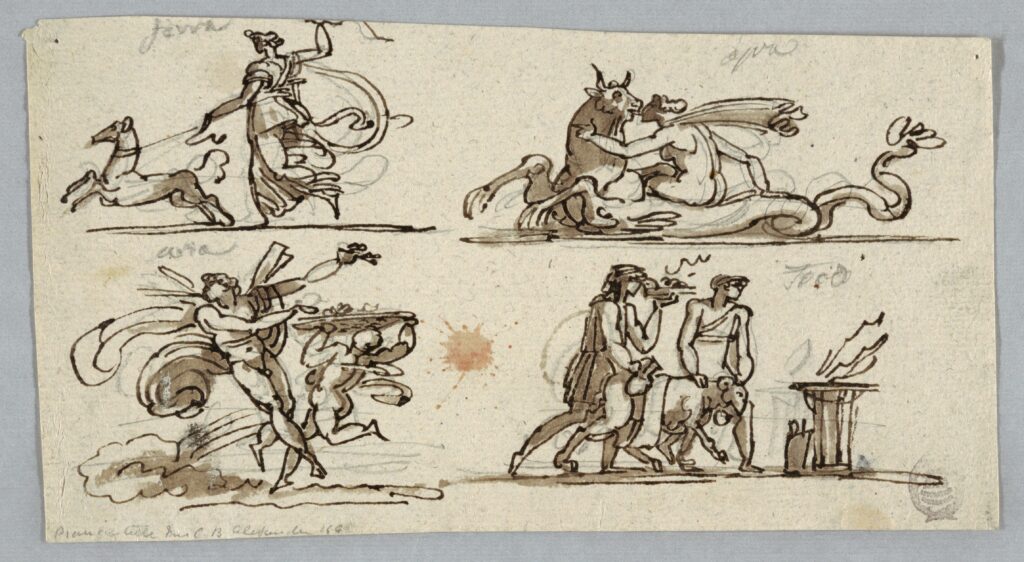

This page gives a brief overview of the four elements according to ancient Greeks and some present understandings and experiments.

Resources for Further Study

- A brief article with illustrations introduces how geysers work.

- The Encyclopedia Brittanica has a brief biography of Marsden Hartley

- The Art Story has more information about Marsden Hartley’s work.

Contemporary Connections

- This article gives an overview of the currently active volcanoes in Italy.

- There are several good resources here for learning about Mt. Vesuvius and Mt. Etna, named “decade volcanoes” by the Deep Carbon Observatory for their activity and impact.