How Wolves Catch Wild Horses

By Anonymous

Annotations by Karen Kilcup

Travelers tell us that the wolves of Mexico have a strange way of catching the wild horses. These horses have a great speed. It is almost impossible for a single cowboy to catch one. The cowboys, when they wish to run them down, have relays of pursuers. First one set of cowboys will chase the horses, then another, and another, until at last the horses are caught by the lasso. But it is only when they are completely tired that they are caught; therefore it would be impossible for the wolves to catch them unless they used strategy, for the flight of the wolves is no so swift as that of the horses.

This is the way the wolves kill the wild horses of the Mexican plains. First, two wolves come out of the woods and begin to play together like two kittens. They gambol about each other and run backward and forward. Then the herd of horses lift their startled heads and gets ready to stampede. But the wolves seem to be so playful that the horses, after watching them for awhile, forget their fears, and continue to graze. Then the wolves in their play come nearer and nearer while other wolves slowly and stealthily creep after them. Then suddenly the enemies surround the herd and make one plunge, and the horses are struggling with the fangs of the relentless foes gripped in their throats.

Anonymous. “How Wolves Catch Wild Horses.” Indian School Journal 6, no. 10 (April 1910): 30.

[1] Here is some commentary. Turn this text red in the color settings if it isn’t already. You will need to name your anchor blocks in the block settings by clicking on it and assigning an ID. I like using the format note-x where x is the number of the note you’re on. Then, add the note number in brackets to your text where you want it to go, highlight the number, and link to #note-x.

[2] Here is some commentary. Turn this text red in the color settings if it isn’t already. You will need to name your anchor blocks in the block settings by clicking on it and assigning an ID. I like using the format note-# where # is the number of the note you’re on.

Contexts

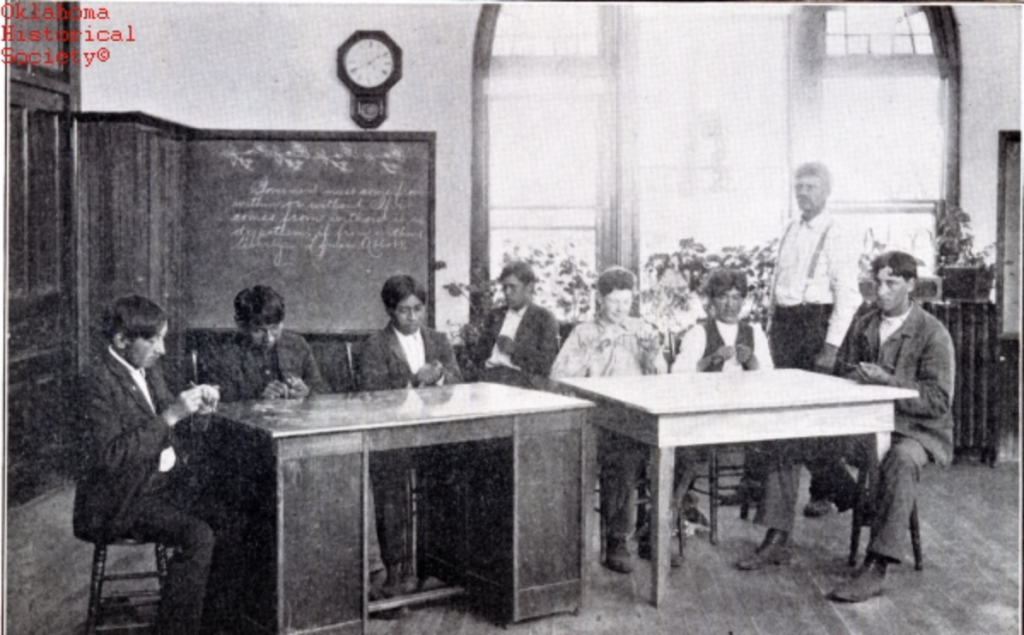

Located in north-central Oklahoma near the Kansas border, the Chilocco Indian Agricultural School (also known as the Haworth Institute, the Chilocco Indian Agricultural School, and the Chilocco Indian School) began taking students in 1884, enrolling 150 from seventeen tribes that first year. Enrollment had more than doubled by 1895, with students coming from various tribes, including the Cherokee, Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Pawnee tribes. The Oklahoma Historical Society notes that “significant enrollment from the so-called ‘Five Civilized Tribes’ did not occur until after 1910 but by 1925, Cherokee constituted the largest single tribal affiliation at the school (26 percent of approximately nine hundred students).” Following World War II and the expansion of public education, the school enrolled mostly students who lacked access to such education.

Like most federally funded Indian schools, Chilocco sought to assimilate Native children into white society. Also like other schools, it stressed “industrial” education—manual and domestic labor—over academic pursuits, aiming to train them as workers for white families. Education at Chilocco was notably militaristic; students attended weekly Christian religious services, also intended to weaken their ties to family and tribe. In the 1950s, student numbers peaked at around 1300, and the school closed in 1980. This sketch highlights animals’ intelligence, a popular topic for American writers of all ages and ethnicities throughout the time period The Envious Lobster encompasses.

Resources for Further Study

- Archuleta, Margaret L., Brenda J. Child, and K. Tsianina Lomawaima (Mvskoke/Creek Nation of Eastern Oklahoma, not enrolled), eds. Away from Home: American Indian Boarding School Experiences, 1879-2000.

- Lomawaima, K. Tsianina (Mvskoke/Creek Nation of Eastern Oklahoma, not enrolled). “Chilocco Indian Agricultural School.” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Oklahoma Historical Society.

- Lomawaima, K. Tsianina. (Mvskoke/Creek Nation of Eastern Oklahoma, not enrolled). They Called It Prairie Light: The Story of Chilocco Indian School (1995).

Contemporary Connections

“At Length with K. Tsianina Lomawaima.” At Length with Steve Scher. February 10, 2016.

“Chilocco Through the Years.” Firethief Productions. Chilocco History Project, August 2, 2019.

Douglas, Crystal. “A Look at the Chilocco Indian School.” The Kaw Nation: People of the Southwind. Fife, Ari. “At one former Native American School in Oklahoma, honoring the dead now falls to alumni.” The Frontier, July 21, 2021.