The Golden Garden Spider

By Effie Lee Newsome

Annotations by Karen Kilcup

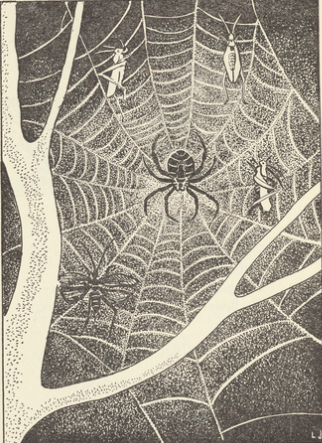

by Lois Mailou Jones. Public Domain.

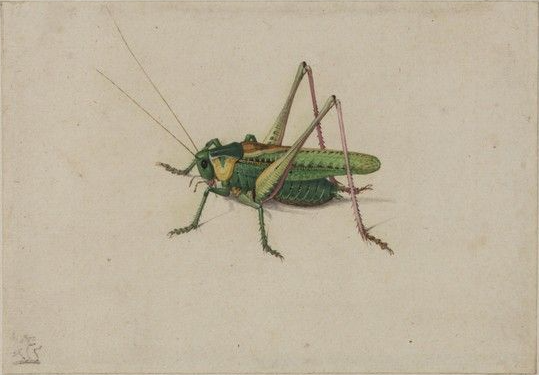

The golden garden spider[1] Has grasshoppers for lunch— At least they hang beside her— I’ve never seen her munch. And yet they swing there every day, And always in a different way. Sometimes I glance at her at dawn, But seldom find her food all gone. It isn’t hard to tell you why— She traps grasshoppers passing by, The wraps them in her web all day. When their long legs get caught they stay, And kicking can’t do any good— Somehow, sometimes—I wish it would.

Newsome, Effie Lee. “The Golden Garden Spider.” Gladiola Garden: Poems of Outdoors and Indoors for Second Grade Readers. Washington, DC: Associated Publishers, 1940, 13.

[1] Probably the Yellow Garden Spider, Argiope aurantia, which spins a circular web.

Contexts

Newsome worked among the many celebrated writers of the Harlem Renaissance, who included Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen, James Weldon Johnson, Zora Neale Hurston, and Anne Spencer, many of them poets. Among her noteworthy contributions to that movement was her writing and editing for W. E. B. Du Bois’s magazine, The Crisis, the official publication of the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People). As John Claborn points out, Du Bois’s political goals embraced the idea of access to natural spaces, and the magazine featured environmental writing by such notable authors as Arna Bontemps, Claude McKay, and Hughes. Newsome contributed to and edited “The Little Page” (“Whimsies for the Younger Folk”), where much of her work emphasized nature. This poem, like many others in The Envious Lobster, whimsically enacts a natural history lesson, while it encourages children’s imagination.

Resources for Further Study

- Claborn, John. “The Crisis, the Politics of Nature, and the Harlem Renaissance: Effie Lee Newsome’s Eco-poetics.” Civil Rights and the Environment in African-American Literature, 1895-1941. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017.

- “Effie Lee Newsome, 1885-1978.” Poets.org. This site provides access to seven of Newsome’s poems.

- Newsome, Effie Lee. Gladiola Garden: Poems of Outdoors and Indoors for Second Grade Readers. Courtesy of the New York Public Library, this site provides access to the entire text.

- Smith, Barbara H. “Beneficial Yellow Garden Spiders,” July 30, 2020. “Yellow Garden Spider, Argiope aurantia.” National Wildlife Federation.

Contemporary Connections

Anonymous. Reading of Newsome’s poem, “The Bronze Legacy.” The illustrations for Gladiola Garden were done by prominent Black artist Loïs Mailou Jones (1905-1998).

Johnston, Amber O’Neal. “African American Poetry: Effie Lee Newsome. Heritage Mom blog.