How I Grew My Corn

By Helen Stevenson

Annotations by Rene Marzuk

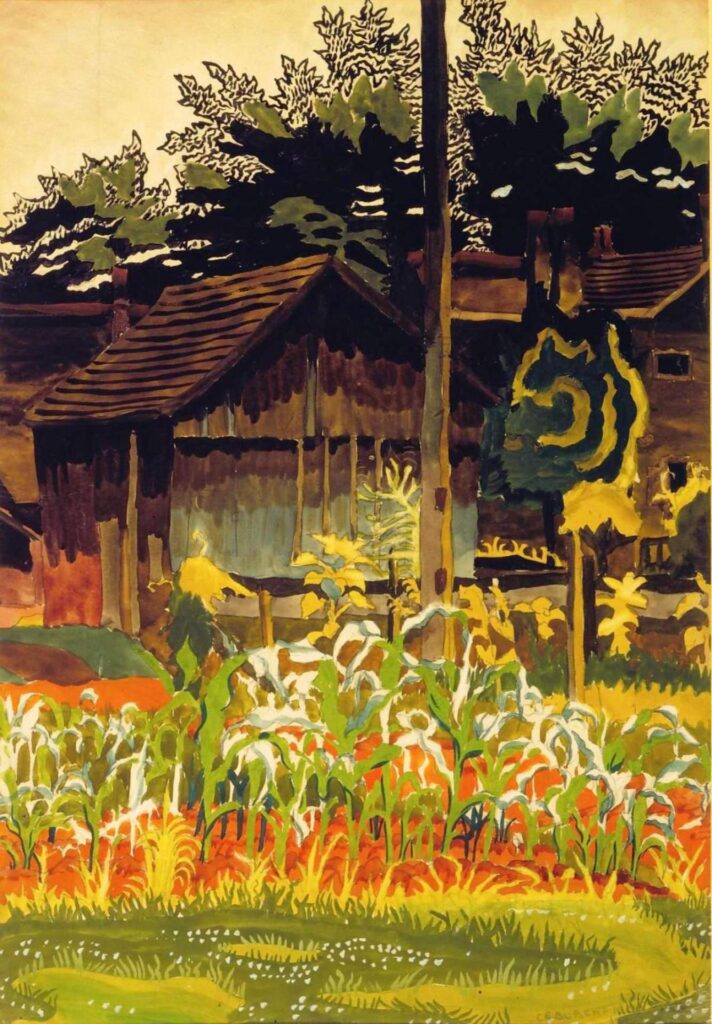

In the year 1914 all the children schools of Cumberland county, N. J., were given the privilege to enter a contest. The girls were to sew, patch or bake and the boys to grow corn or sweet potatoes.[1] As I liked to work out of doors I entered the corn contest. The rules were that the boys should do all the work themselves; the girls were to do all except the plowing. We were to have one-tenth of an acre and find our own seed.

When I first asked my father for a piece of ground he said, “I can not spare it.” But at last he consented to give me a plot next to the woods, if I could get one-tenth of an acre from it.

One night after school I went down and measured off my ground. On the nineteenth of May I took my old friend, Harry (the horse), whom I had worked in the field before, and went down to my farm, as I called it. There I worked until I had an even seed bed, after which I marked it out and fertilized it. On the next day I planted my corn putting three grains in a hill and covering it with a hoe.

I paid it daily visits and when it was about two inches high I replanted it and hoed the hills which were up. From then on I hoed and cultivated my crop and kept it free from grass until it grew too large to be attended. As it was a dry season that year, the stalks next to the woods did not grow to their full height.

I also had visitors to come and see my corn. This gave me more courage to go on as all the other girls and boys in Fairfield township had given it up. Mother and father had also tried to discourage me, but I kept on.

I did not cut it down until November. I then measured my highest stalks which were from fifteen to sixteen feet. On the day before the contest I stayed home to get my corn ready. Mother and father coaxed me not to take it away, but I did.

After selecting ten of my largest and best ears of corn, I put them in a basket and went to Bridgeton with one of my neighbors, as father would not take them. After arriving in town I carried my corn up to the Court House.

The next day I went to school and in the afternoon my teacher received a telephone message which said I had won a prize. I was very happy indeed; mother and father were surprised.

On Saturday went to the Bridgeton Library annex where things were being exhibited and saw my corn with a prize tag on it which made me feel very proud. I then went to the Commercial League room where the prizes were distributed. I received my prize and went home very happy and full of courage to try again.

The amount I cleared for my corn was $12.00–$5.00 for my fodder, $4.00 for my seed and $3.00 for my prize.

I am going to try again this year and I think all boys and girls who have the privilege of learning to farm should do so–for there is nothing better than life on a farm.

STEVENSON, HELEN. “HOW I GREW MY CORN.” THE CRISIS 8, NO. 6 (OCTOBER 1914): 273-74.

[1] In February, 1914 the Department of Public Instruction from Trenton, N.J. published an elementary agriculture manual on corn growing. This document’s foreword references “the widespread interested aroused at the present time by the organization of ‘Corn Clubs’ [that] makes a study of corn one of the best ways of introducing agriculture in the elementary grades of the public schools of the State.” The section “Suggestions for Girls’ Participation in the Study of Agriculture” speaks directly to Helen Stevenson’s experience: “The girls may do exactly the same work as the boys . . . Not a few girls will prefer this plan and some of our girls have grown corn quite as successfully as boys.”

Contexts

Starting in 1912, the October issues of The Crisis, the official magazine of the NAACP, were dedicated to children. A typical edition of these children’s numbers would contain a special editorial piece and two or three literary works specifically for children, while still including the serious pieces about contemporary issues with a focus on race that The Crisis was known for. These October numbers were sprinkled with children’s photographs sent in by the readers.

In his first editorial for the Children’s number in 1912, W. E. B. Du Bois wrote that “there is a sense in which all numbers and all words of a magazine of ideas myst point to the child—to that vast immortality and wide sweep and infinite possibility which the child represents.”

The success of The Crisis’ children’s number led to the standalone The Brownies’ Book, a monthly magazine for African American children that circulated from January 1920 to December 1921 under the editorship of Du Bois, Augustus Granville Dill, and Jessie Fauset.

Definitions from Oxford English Dictionary:

fodder: Food for cattle, horses, or other animals.

Resources for Further Study

- After the Civil War (1861-1865) and the subsequent abolition of slavery, former slaves were notoriously promised “forty acres and a mule” as a compensation for their unpaid work during slavery. Ultimately, this attempted redistribution failed and by the end of the Reconstruction period (1865-1877) lands were returned to their previous white owners.

- A timeline of interactions between black farmers and the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) from 1920 to 2021.

- Oxford Bibliographies‘ page on African American agriculture and agricultural labor.

- TED-Ed short animation on the history of corn. Indigenous peoples from southern Mexico domesticated corn about 10,000 years ago. Today, this crop accounts for more than one tenth of our global crop production!

Contemporary Connections

Data on female producers from the 2017 Census of Agriculture.

“Living off the land: the new sisterhood of Black female homesteaders.”