The Strawberry Woman

By T. S. Arthur

Annotations by Josh benjamin

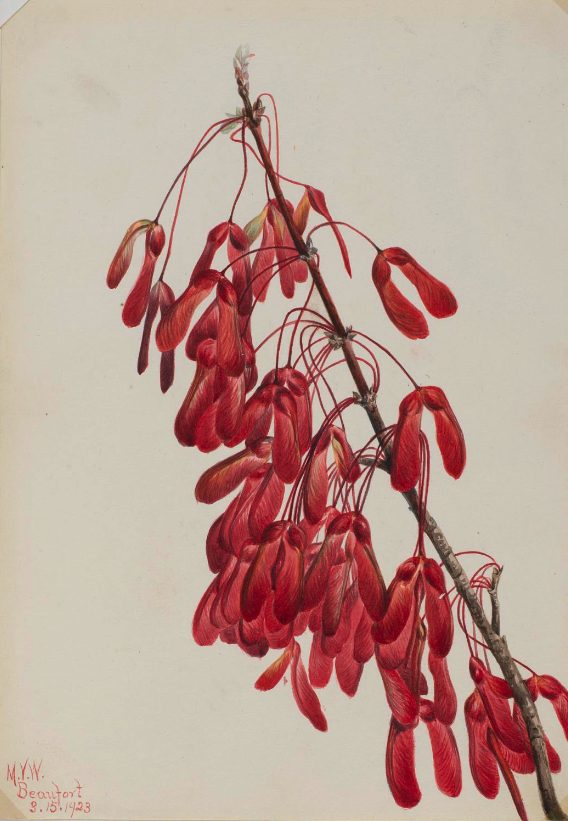

Stipple engraving in brown, with hand-colored additions, on cream wove paper, 1799. The

Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, I.L.

“Strawb’rees! Strawb’rees!” cried a poorly clad, tired-looking woman, about eleven o’clock, one sultry June morning. She was passing a handsome house in Walnut street, into the windows of which she looked earnestly, in the hope of seeing the face of a customer. She did not look in vain, for the shrill sound of her voice brought forward a lady, dressed in a silk mourning wrapper, who beckoned her to stop. The woman lifted the heavy tray from her head, and placing it upon the doorstep, sat wearily down.

“What’s the price of your strawberries?” asked the lady as she came to the door.

“Ten cents a box, madam. They’re right fresh.”

“Ten cents!” replied the lady in a tone of surprise, drawing herself up and looking grave. Then shaking her head, and compressing her lips firmly, she added—

“I can’t give ten cents for strawberries. It’s too much. I’ll give you forty cents for five quarts, and nothing more.”

“But madam, they cost me within a trifle of eight cents a quart.”

“I can’t help that. You paid too much for them, and this must be your loss not mine, if I buy your strawberries. I never pay for other people’s mistakes. I understand the use of money much better than that.”

The poor woman did not feel very well. The day was unusually hot and sultry, and her tray felt heavier and tired her more than usual. Five boxes would lighten it, and if she sold her berries at eight cents, she would clear two cents and a half, and that made her something.

“I’ll tell you what I will do,” she said, after thinking a few moments; I don’t feel as well as usual to-day, and my tray is heavy. Five boxes sold will be something. You shall have them at nine cents. They cost me seven and a half, and I’m sure it’s worth a cent and a half a box to cry them about the streets such hot weather as this.”

“I have told you, my good woman, exactly what I will do,” said the customer, with dignity, “If you are willing to take what I offer you, say so; if not we need’nt stand here any longer.”

“Well, I supposed you will have to take them,” replied the strawberry woman, seeing that there was no hope of doing better. “But it’s too little.”

“It’s enough,” said the lady, as she turned to call a servant. Five boxes of fine large strawberries were received, and forty cents paid for them. The lady re-entered the parlor, pleased at her good bargain, while the poor woman turned from the door, sad and disheartened. She walked nearly the distance of a square before she could trust her voice to utter the monotonous cry of

“Strawb’rees! Strawb’rees!”

An hour afterwards, a friend called upon Mrs. Mier, the lady who had bought the strawberries. After talking about various matters and things, interesting to lady housekeepers, Mrs. Mier said—

“How much did you pay for the strawberries, this morning?”

“Ten cents.”

“You paid too much. I bought them for eight.”

“For eight! Were they good ones?”

“Step into the dining room, and I will show them to you.”

The ladies stepped into the dining room, when Mrs. Mier displayed her large red berries, which were really much finer than she had supposed them to be.

“You did’nt get them for eight cents,” remarked the visitor incredulously.

“Yes, I did; I paid forty cents for five quarts.”

“While I paid fifty, for some not near so good.”

“I suppose you paid just what you were asked.”

“Yes, I always do that. I buy from one woman during the season, who agrees to furnish me at the regular market price.”

“Which you always find to be two or three cents above what you can get them for in the market.”

“You always buy in the market.”

“I bought these from a woman at the door.”

“Did she only ask eight cents for them?”

“Oh, no, she asked ten cents, and pretended that she got twelve and a half for the same quality of berries yesterday. But I never give these people what they ask.”

“Well, I never can find it in my heart to ask a poor tired-looking woman at my door, to take a cent less for her fruit than she asks me. A cent or two, while it is of little account to me, must be of great importance to her.”

“You are a very poor economist, I see,” said Mrs. Mier. “If that is the way you deal with every one, your husband, no doubt, finds his expense account a very serious item.”

“I don’t know about that. He never complains. He allows me a certain sum every week to keep the house, and find my own and the children’s clothes; and so far from ever calling on him for more, I always have a fifty or a hundred dollars lying by me.”

“You must have a precious large allowance, then, considering your want of economy in paying every body just what they ask for their things.”

“Oh, no! I don’t do that exactly, Mrs. Mier. If I consider the price of a thing too high, I don’t buy it.”

“You paid too high for your strawberries, to-day.”

“Perhaps I did, although I am by no means certain.”

“You can judge for yourself. Mine cost but eight cents, and you own that they are superior to yours at ten cents.”

“Still, yours may have been too cheap, instead of mine too dear.”

“Too cheap! that is funny! I never saw anything too cheap in my life. The great trouble is that everything is too dear. What do you mean by too cheap.”

“The person who sold them to you may not have made profit enough upon them to pay for her time and labor. If this were the case, she sold them to you too cheap.”

“Suppose she paid too high for them? Is the purchaser to pay for her error?”

“Whether she did so, it would be hard to tell, and even if she had made such a mistake, I think it would be more just and humane to pay her a price that would give her a fair profit, instead of taking from her the means of buying bread for her children. At least, this is my way of reasoning.”

“And a precious lot of money it must take to support such a system of reasoning. But how much, pray, do you have a week to keep the family. I am curious to know.”

“Thirty-five dollars.”

“Thirty-five dollars! You are jesting.”

“Oh, no! That is exactly what I receive, and as I have said, I find the sum ample.”

“While I receive fifty dollars a week,” said Mrs. Mier, “and am forever calling on my husband to settle some bill or other for me. And yet I never pay the exorbitant prices asked by every body for every thing. I am strictly economical in my family. While other people pay their domestics a dollar and a half and two dollars a week, I give but a dollar and a quarter each to my cook and chambermaid, and require the chambermaid to help the washerwoman on Mondays. Nothing is wasted in my kitchen, for I take care in marketing, not to allow room for waste. I don’t know how it is that you save money on thirty-five dollars with your system, while I find fifty dollars inadequate with my system.”

The exact difference in the two systems will be clearly understood by the reader when he is informed that although Mrs. Mier never paid anybody as much as was at first asked for an article, and was always talking about economy, and trying to practise it, by withholding from others what was justly their due, as in the case of the strawberry woman, yet she was a very extravagant person, and spared no money in gratifying her own pride. Mrs. Gilman, her visitor, was on the contrary, really economical, because she was moderate in all her desires, and was usually as well satisfied with an article of dress or furniture that cost ten or twenty dollars, as Mrs. Mier was with one that cost forty or fifty dollars. In little things, the former was not so particular as to infringe the right of others, while in large matters she was careful not to run into extravagance in order to gratify her own or children’s pride and vanity, while the latter pursued a course directly opposite.

Mrs. Gilman was not as much dissatisfied on reflection, about the price she had paid for her strawberries, as she had felt at first.

“I would rather pay these poor creatures two cents a quart too much than too little,” she said to herself—“dear knows they earn their money hard enough, and get but a scanty portion after all.”

Although the tray of the poor strawberry woman, when she passed from the presence of Mrs. Mier, was lighter by five boxes, her heart was heavier, and that made her steps more weary than before. The next place at which she stopped, she found the same disposition to beat her down in her price.

“I’ll give you nine cents, and take four boxes,” said the lady.

“Indeed madam, that is too little,” replied the woman; ten cents is the lowest at which I can sell them, and make even a reasonable profit.”

“Well, say thirty-seven and a half for four boxes, and I will take them. It is only two cents and a half less than you ask for them.”

“Give me a fip, ma!—there comes the candy-man!” exclaimed a little fellow, pressing up to the side of the lady. “Quick ma! Here candy man!”

“Get a levy’s worth mother, do, won’t you? Cousin Lu’s coming to see us to-morrow.”

“Let him have a levy’s worth, candy-man. He’s such a rogue, I can’t resist him,” responded the mother. The candy was counted out, and the levy paid, when the man retired in his usual good humor.

“Shall I take these strawberries for thirty-seven and a half cents?” said the lady, the smile fading from her face. “It is all I am willing to give.”

“If you won’t pay any more, I must n’t stand for two cents and a half,” replied the woman, “although they would nearly buy a loaf of bread for the children,” she mentally added.

The four boxes were sold for the sum offered, and the woman lifted the tray upon her head, and moved on again. The sun shone still hotter and hotter as the day advanced. Large beads of perspiration rolled from the throbbing temples of the strawberry woman, as she passed wearily up one street and down another, crying her fruit at the top of her voice. At length all was sold but five boxes, and now it was past one o’clock. Long before this, she ought to have been at home. Faint from over-exertion, she lifted her tray from her head, and placing it upon a door-step she sat down to rest. As she sat thus, a lady came up and paused at the door of the house as if about to enter.

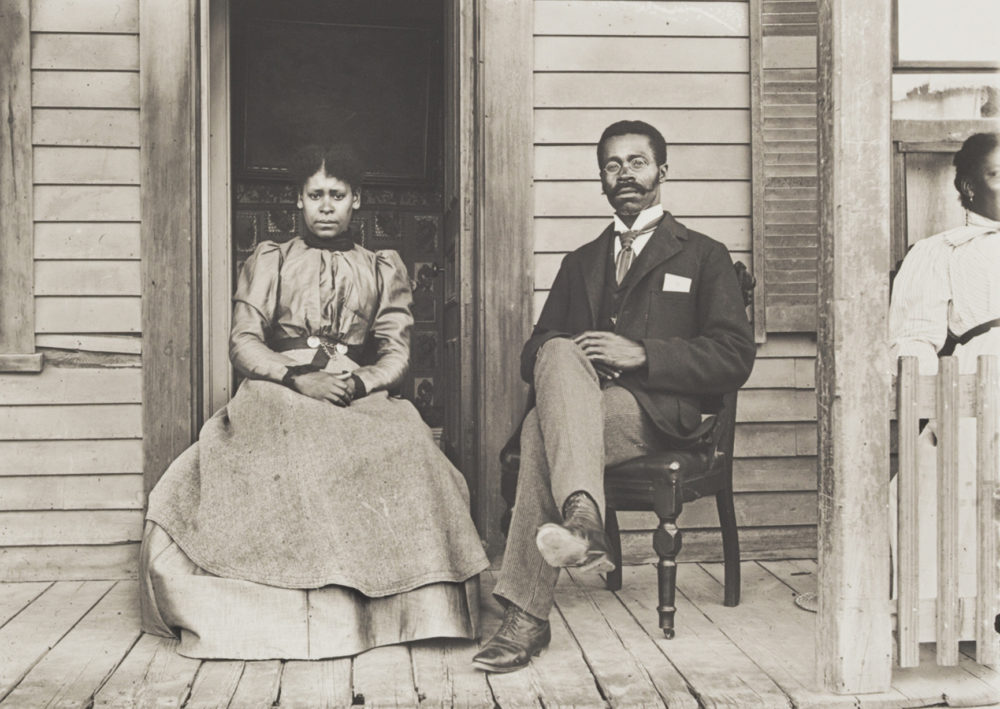

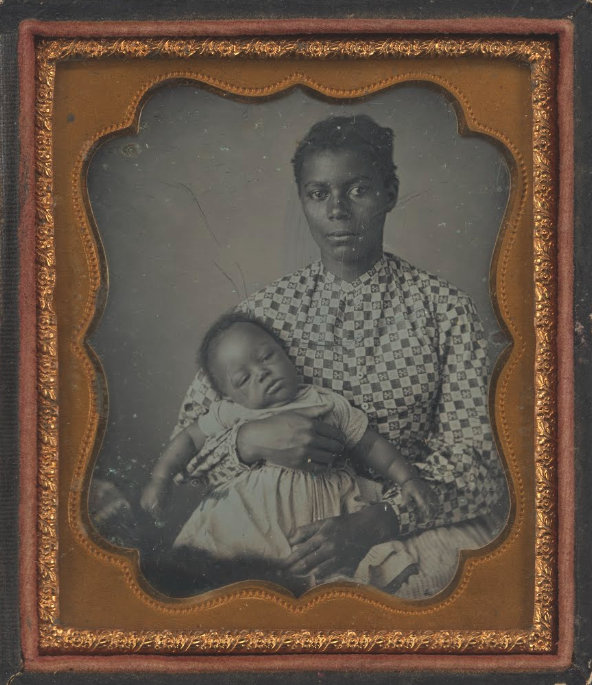

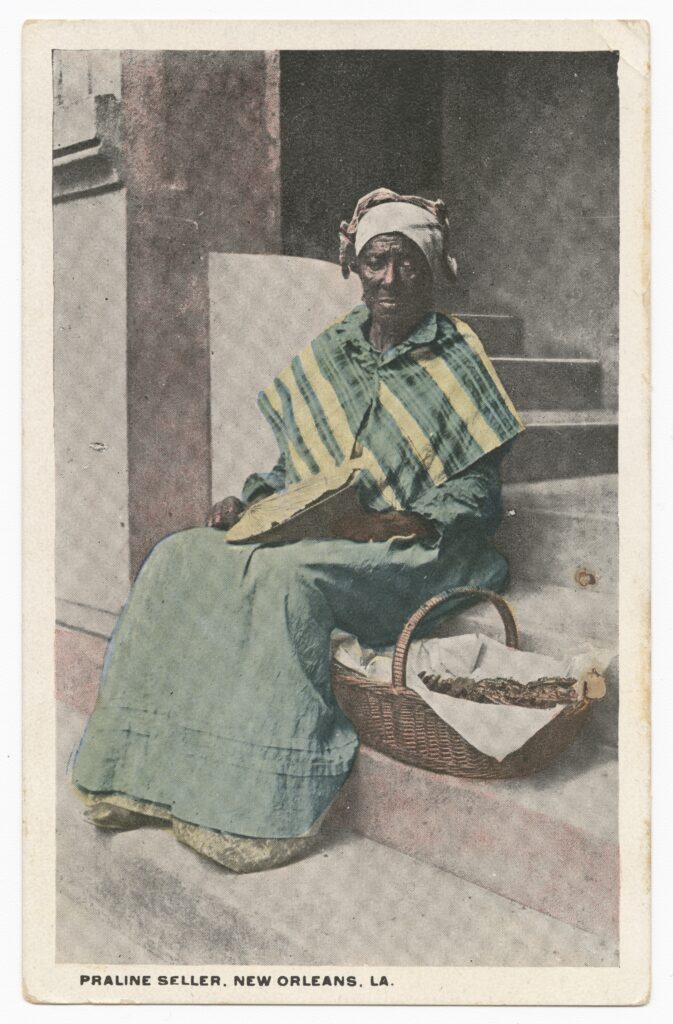

Museum of African American History and Culture, Washington, D.C.

“You look tired, my good woman,” she said, kindly. “This is a very hot day for such hard work as yours. How do you sell your strawberries?”

“I ought to have ten cents for them, but nobody seems willing to give ten cents, to-day, although they are very fine, and cost me as much as some I have got twelve and a half for.”

“How many boxes have you?”

“Five, ma’am.”

“They are very fine, sure enough,” said the lady, stopping down and examining them; and well worth ten cents. I’ll take them.”

“Thanky, ma’am. I was afraid I should have to take them home,” said the woman, her heart bounding up lightly.

The lady rang the bell, for it was at her door that the tired strawberry-woman had stopped to rest herself. While she was waiting for the door to be opened, the lady took from her purse the money for her strawberries, and handing it to the woman, said,

“Here is your money. Shall I tell the servant to bring you a glass of cool water? You are hot and tired.”

“If you please, ma’am,” said the woman, with a grateful look.

The water was sent out by the servant who was to receive the strawberries, and the tired woman drank it eagerly. Its refreshing coolness flowed through every vein, when she took up her tray to return home, both heart and step were lighter.

The lady, whose benevolent feelings had prompted her to the performance of this little act of kindness, could not help remembering the woman’s grateful look. She had not done much—not more than it was one’s duty to do; but the recollection of even that was pleasant, far more pleasant than could possibly have been Mrs. Mier’s self-congratulations at having saved ten cents on her purchase of five boxes of strawberries, notwithstanding the assurance of the poor woman who vended them, that, at the reduced rate, her profit on the whole would only be two cents and a half.

After dinner, Mrs. Mier went out and spent thirty dollars in purchasing jewelry for her eldest daughter, a young lady not yet eighteen years of age. That evening, at the tea-table, the strawberries were highly commended as being the largest and most delicious in flavor of any they had yet had; in reply to which Mrs. Mier stated, with an air of peculiar satisfaction, that she had got them for eight cents a box when they were worth at least ten cents.

“The woman asked me ten cents,” she said, “but I offered her eight and she took it.”

While the family of Mrs. Mier were enjoying their pleasant repast, the strawberry woman sat at a small table, around which were gathered three young children, the oldest but six years of age. She had started out in the morning with thirty boxes of strawberries, for which she was to pay seven and a half cents a box. If all had brought the ten cents a box, she would had made seventy-five cents; but such was not the case. Rich ladies had beaten her down in price—had chaffered with her for the few pennies of profits to which her hard labor entitled her—and actually robbed her of the meagre pittance she strove to earn for her children. Instead of realizing the small sum of seventy-five cents, she had cleared only forty-five cents [1]. With this, she bought a little Indian meal [2] and molasses for her own and her children’s supper and breakfast.

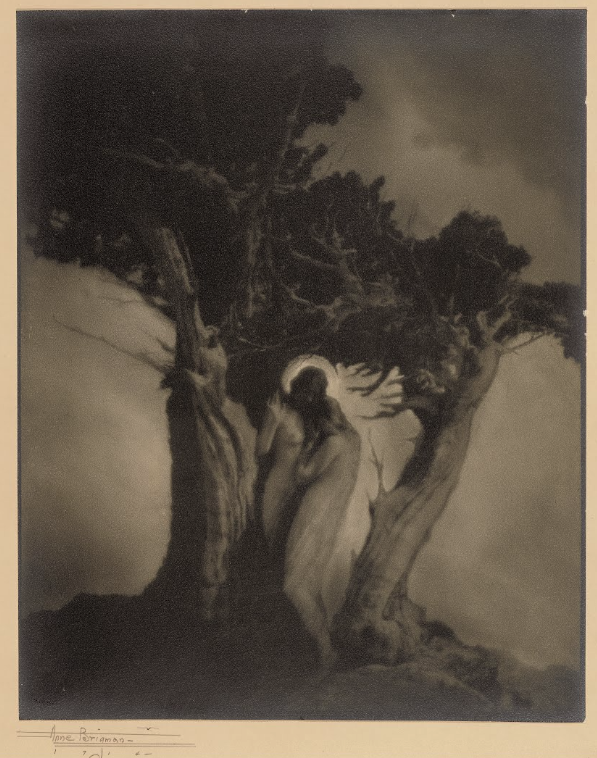

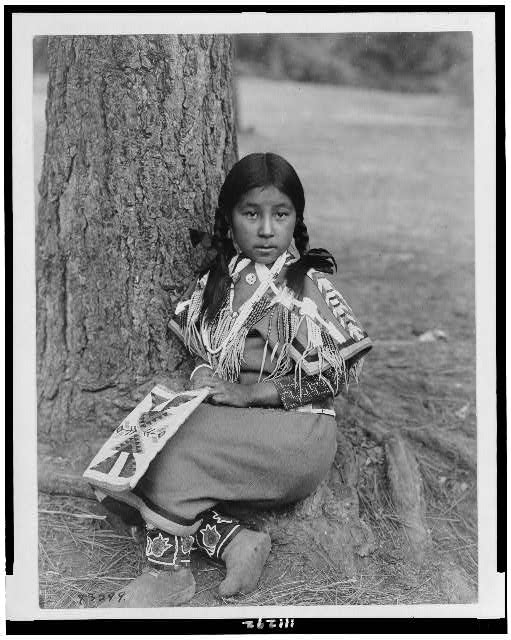

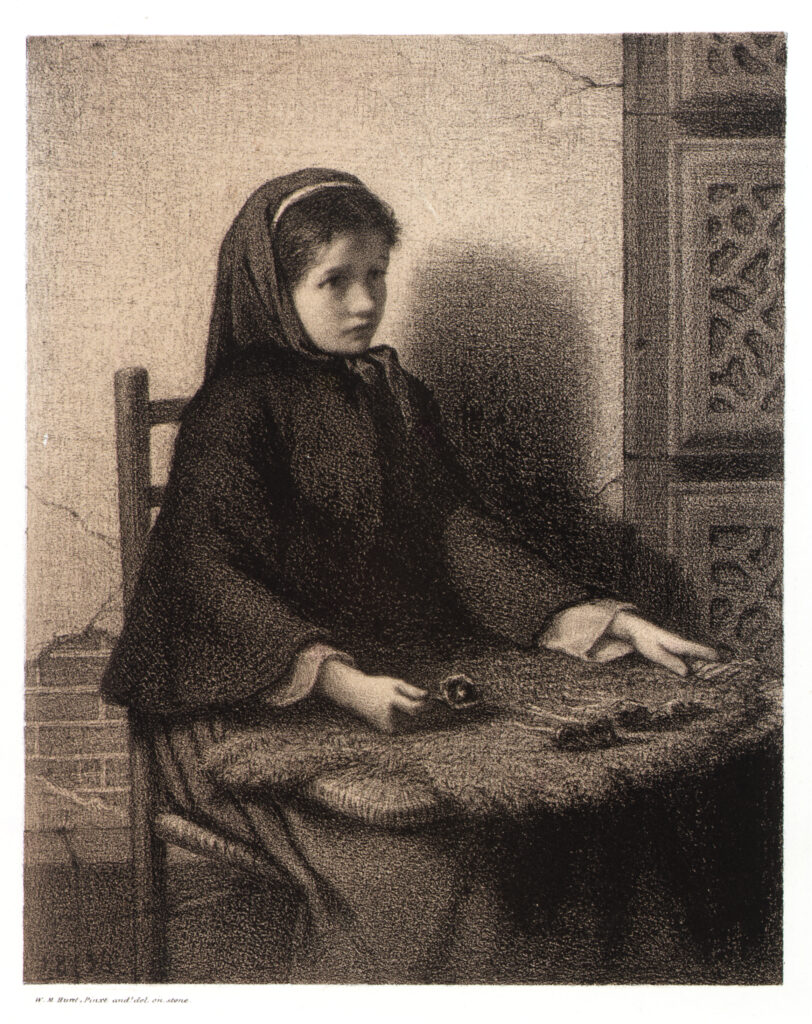

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.

As she sat with her children, eating the only food she was able to provide for them, and thought of what had occurred during the day, a feeling of bitterness toward her kind came over her; but the remembrance of the kind words and the glass of cool water, so timely and thoughtfully tendered to her, was like leaven in the waters of Marah [3]. Her heart softened, and with the tears stealing to her eyes, she glanced upward, and asked a blessing on her who had remembered that, though poor, she was still human.

Economy is a good thing and should be practised by all, but it should show itself in denying ourselves, not in oppressing others. We see persons spending dollar after dollar foolishly one hour, and in the next trying to save a penny piece of a wood-sawyer, coal-heaver, or market woman. Such things are disgraceful if not dishonest.

Arthur, T.S. “The STrawberry Woman.” The youth’s companion 21, No. 19 (September 1847): 73-74.

[1] The forty-five cents that the strawberry woman makes would be equivalent to $15.87 in 2022. Mrs. Gilman’s $35 a week would be $1,234, and Mrs. Mier’s $50 a week for the household would be $1,763. Over the course of a year, Mrs. Mier receives the equivalent of nearly $92,000 (an inadequate amount), she pays each of her domestic staff a yearly salary the equivalent of just under $2,300.

[2] Indian meal is a term for cornmeal, which was used for many recipes, such as these, from 1800s cookbooks: https://vintagerecipesandcookery.com/cooking-with-corn-meal/

[3] Holy Bible, New King James Version: “So Moses brought Israel from the Red. Sea; then they went out into the Wilderness of Shur. And they went three days in the wilderness and found no water. Now when they came to Marah, they could not drink the waters of Marah, for they were bitter. Therefore the name of it was called Marah. And the people complained against Moses, saying, ‘What shall we drink?’ So he cried out to the Lord, and the Lord showed him a tree. When he cast it into the waters, the waters were made sweet.” (Exodus 15:22-25)

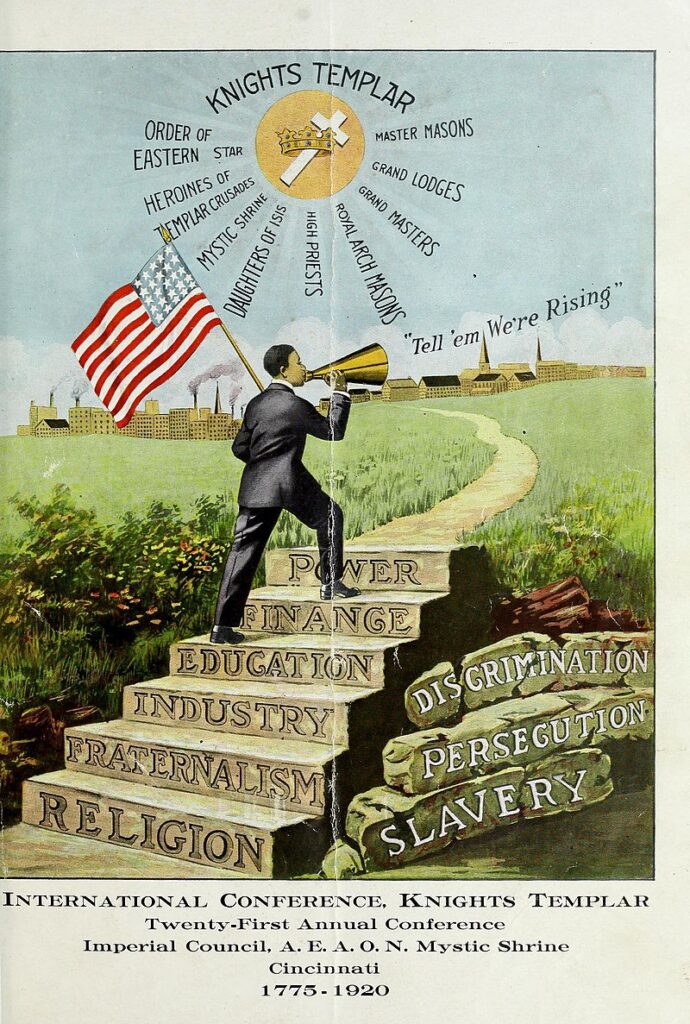

Contexts

Timothy Shay Arthur moved to Philadelphia in 1841, and given the mention of Walnut Street and the Pennsylvania slang noted in the definitions below, this story is likely set in Philadelphia. Much of Arthur’s writing concerned morality, particularly temperance, which inspired his 1854 publication Ten Nights in a Bar-Room and What I Saw There, the most successful temperance book of the time. The Pennsylvania Center for the Book has a brief biography of Arthur’s life and career.

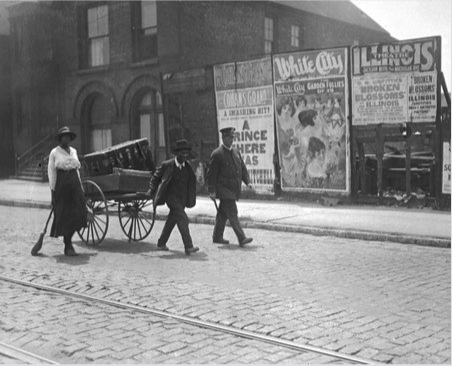

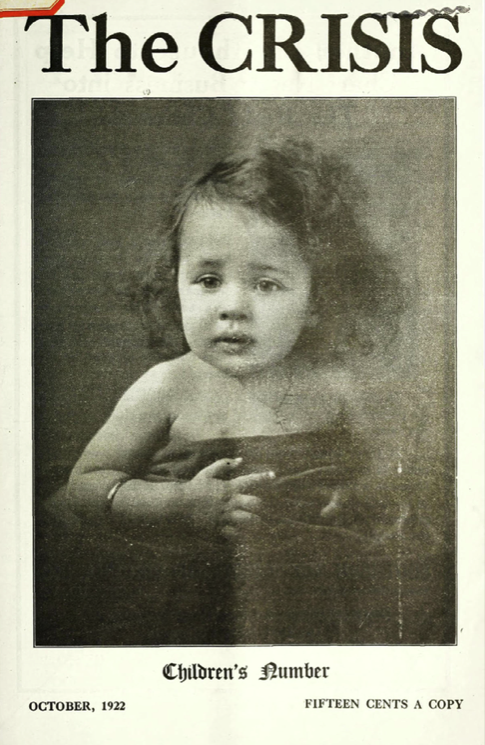

This story appeared amid ongoing riots and violence perpetrated by white Philadelphians against Black neighborhoods and churches, which were only exacerbated by the growing abolition movement and the Pennsylvania State Constitution of 1838 rescinding the right for free Black men to vote. The Nativist movement continued to gain ground in Philadelphia and elsewhere throughout the 1840s and extended to anti-Irish Catholic sentiment, which was further formalized during the next decade with the American or Know Nothing Party.

Definitions from Oxford English Dictionary:

chaffer: To treat about a bargain; to bargain, haggle about terms or price.

chambermaid: A woman employed to clean the bedrooms in a house or hotel.

dear: At a high price; at great cost; usually with such verbs as buy, cost, pay, sell, etc.

domestic: A household servant or attendant.

fip: Short for fipenny bit; 1860 usage from J.R. Bartlett’s Dictionary of Americanisms: In Pennsylvania, and several of the Southern States, the vulgar name for the Spanish half-real

levy: U.S. regional ‘The sum of twelve and a half cents; a “bit” (Cent. Dict.); from J.R. Bartlett’s Dictionary of Americanisms: In Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia, the Spanish real…twelve and a half cents.

trifle: A ‘small sum of money, or a sum treated as of no moment; a slight ‘consideration’.

Resources for Further Study

- The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia has a summary of the riots of the 1830s and 1840s, along with a wealth of essays about the city’s history in the first half of the 19th century.

- During the riots, many all-white volunteer firefighting companies refused to help, and when Good Will Engine Company responded to a fire rioters set at the California House, a rioter shot and killed one of the white firefighters.

- A silver trumpet presented to the Good Will Engine Company is an emblem of part of the complex history of philanthropy in the U.S. While this essay suggests a charitable attitude toward the less fortunate, the National Museum of American History and the Smithsonian’s Philanthropy Initiative looks at the “complicated legacy” of helping others.

Contemporary Connections

While this story doesn’t engage with the growing nativist sentiment of its time, Lorraine Boissoneault argues that the movement’s effects are still visible in American politics.