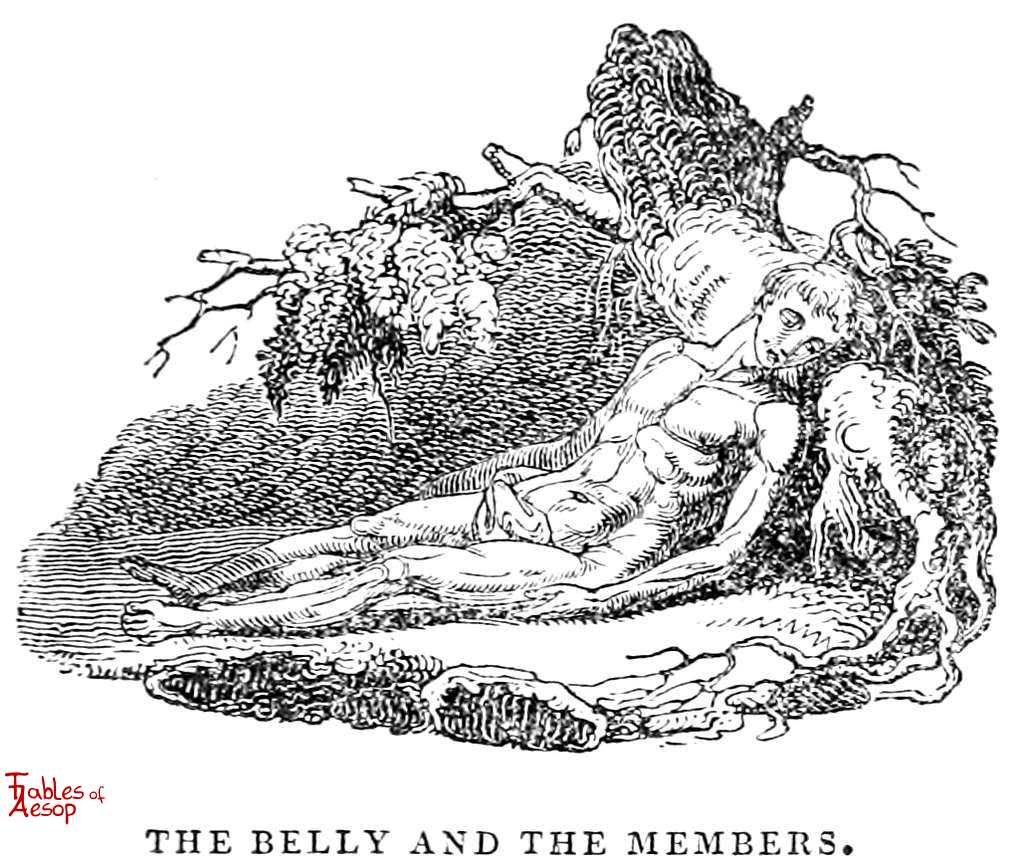

The Belly and the Members: A Fable [1]

By Æsop

Annotations by Ian McLaughlin

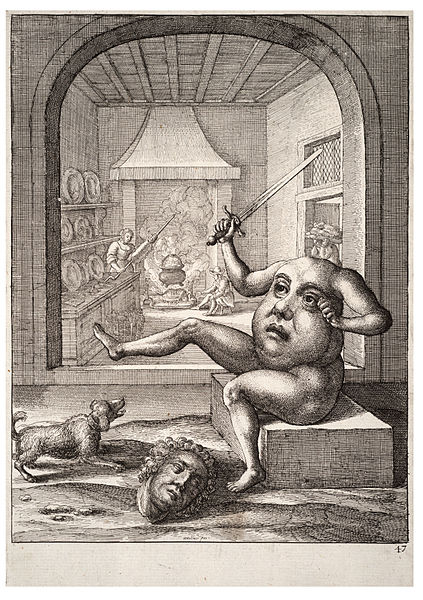

by John Ogilby, 1665. Fisher Library at the University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada.

The Members of the Body once rebelled against the Belly. “You,” they said to the Belly, “live in luxury and sloth, and never do a stroke of work; while we not only have to do all the hard work there is to be done, but are actually your slaves and have to minister to all your wants. Now, we will do so no longer, and you can shift for yourself for the future.” They were as good as their word, and left the Belly to starve. The result was just what might have been expected: the whole Body soon began to fail, and the Members and all shared in the general collapse. And then they saw too late how foolish they had been.

In the former days, when the Belly and the other parts of the body enjoyed the faculty of speech, and had separate views and designs of their own, each part, it seems, in particular for himself and in the name of the whole, took exception at the conduct of the Belly, and were resolved to grant him supplies no longer.

They said they thought is very hard that he should lead an idle good-for-nothing life, spending and squandering away, upon his own ungodly guts, all the fruits of their labor; and that, in short, they were resolved, for the future, to strike off his allowance, and let him shift for himself as well as he could. The Hands protested they would not lift up a finger to keep him from starving; and the Mouth wished he might never speak again if he took in the least bit of nourishment for him as long as he lived; and, say the Teeth, may we be rotten if ever we chew a morsel for him for the future. This solemn league and covenant was kept as long as anything of that kind can be kept, which was until each of the rebel members pined away to the skin and bone, and could hold out no longer. Then they found there was no doing without the Belly, and that, as idle and insignificant as he seemed, he contributed as much to the maintenance and welfare of all the other parts as they did to his.

Application

This fable was spoken by Menenius Agrippa, a famous Roman consul and general, when he was deputed by the senate to appease a dangerous tumult and insurrection of the people. The many wars that nation was engaged in, and the frequent supplies they were obliged to raise, had so soured and inflamed the minds of the populace, that they were resolved to endure it no longer, and obstinately refused to pay the taxes which were levied upon them. It is easy to discern how the great man applied this fable. For, if the branches and members of a community refuse the government that aid which its necessities require, the whole must perish together. The rulers of a State, as idle and insignificant as they may sometimes seem are yet as necessary to be kept up and maintained in a proper and decent grandeur, as the family of each private person is in a condition suitable to itself. Every man’s enjoyment of that little which he gains by his daily labor depends upon the government’s being maintained in a condition to defend and secure him in it.

Menenius Agrippa, a Roman consul, being deputed by the senate to appease a dangerous tumult and sedition of the people, who refused to pay the taxes necessary for carrying on the business of the state, convinced them of their folly by delivering to them the following fable.

My friends and countrymen, said he, attend to my words. It once happened that the members of the human body, taking some exception at the conduct of the Belly, resolved no longer to grant him the usual supplies. The Tongue first, in a seditious speech, aggravated their grievances; and after highly extolling the activity and diligence of the Hands and Feet, set forth how hard and unreasonable it was that the fruits of their labor should be squandered away upon the insatiable cravings of a fat and indolent paunch, which was entirely useless, and unable to do anything towards helping himself.

This speech was received with unanimous applause by all the members. Immediately the Hands declared they would work no more; the Feet determined to carry no farther the load with which they had hitherto been oppressed; nay, the very Teeth refused to prepare a single morsel more for his use. In this distress the Belly besought them to consider maturely, and not foment so senseless a rebellion. There is none of you, says he, but may be sensible that whatsoever you bestow upon me is immediately converted to your sue, and dispersed by me for the good of you all into every limb. But he remonstrated in vain; for during the clamors of passion the voice of reason is always unregarded. It being therefore impossible for him to quiet the tumult, he was starved for want of their assistance, and the body wasted away to a skeleton. The Limbs, grown weak and languid, were sensible at last of their error, and would fain have returned to their respective duty, but it was now too late; death had taken possession of the whole, and they all perished together.

We should well consider, whether the removal of a present evil does not tend to produce a greater.

Æsop. “The belly and the members,” in Aesop’s FAbles, Translated by V. S. Vernon Jones. New York: AVenel books, 1912. www.gutenberg.org/files/11339/11339-h/11339-h.htm

Æsop. “The belly and the members,” inThe Fables of Æsop With a Life of the Author, 175. New York: Hurd and Houghton, 1868. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.b000938579&view=1up&seq=197.

Aesop. “The belly and the members,” in Aesop’s Fables: Together With the Life of Aesop, by Mons. de meziriac, 51. Chicago: The Henneberry Company, 1897. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015005534220&view=1up&seq=53.

[1] Because this fable is short and has many translations, I’ve included three versions.

Contexts

Æsop is likely the most famous fabulist of all time. His stories have been used to teach children the values of many cultures over many centuries. Many famous children’s stories, such as “The Tortoise and the Hare“, “City Mouse and Country Mouse“, and “The Lion and the Mouse” are based on his work.

Resources for Further Study

- For more information on what makes a story a fable, see this introduction to the text by G.K. Chesterton.

Contemporary Connections

There are countless picture books and anthologies based on Æsop’s works. The Library of Congress has turned “The Aesop for Children: with Pictures” by Milo Winter (1919) into an interactive ebook.