The Black Fairy

By Fenton Johnson

Annotations by Rene Marzuk

Little Annabelle was lying on the lawn, a volume of Grimm before her. Annabelle was nine years of age, the daughter of a colored lawyer, and the prettiest dark child in the village.[1] She had long played in the fairyland of knowledge, and was far advanced for one of her years. A vivid imagination was her chief endowment, and her story creatures often became real flesh-and-blood creatures.

“I wonder,” she said to herself that afternoon, “if there is any such thing as a colored fairy? Surely there must be, but in this book they’re all white.”

Closing the book, her eyes rested upon the landscape that rolled itself out lazily before her. The stalks in the cornfield bent and swayed, their tassels bowing to the breeze, until Annabelle could have easily sworn that those were Indian fairies. And beyond lay the woods, dark and mossy and cool, and there many a something mysterious could have sprung into being, for in the recess was a silvery pool where the children played barefooted. A summer mist like a thin veil hung over the scene, and the breeze whispered tales of far-away lands.

Hist! Something stirred in the hazel bush near her. Can I describe little Annabelle’s amazement at finding in the bush a palace and a tall and dark-faced fairy before it?

“I am Amunophis, the Lily of Ethiopia,” said the strange creature. “And I come to the children of the Seventh Veil.”[2]

She was black and regal, and her voice was soft and low and gentle like the Niger on a summer evening.[3] Her dress was the wing of the sacred beetle, and whenever the wind stirred it played the dreamiest of music.[4] Her feet were bound with golden sandals, and on her head was a crown of lotus leaves.

“And you’re a fairy?” gasped Annabelle.

“Yes, I am a fairy, just as you wished me to be. I live in the tall grass many, many miles away, where a beautiful river called the Niger sleeps.” And stretching herself beside Annabelle, on the lawn, the fairy began to whisper:

“I have lived there for over five thousand years. In the long ago a city rested there, and from that spot black men and women ruled the world. Great ships laden with spice and oil and wheat would come to its port, and would leave with wines and weapons of war and fine linens. Proud and great were the black kings of this land, their palaces were built of gold, and I was the Guardian of the City. But one night when I was visiting an Indian grove the barbarians from the North came down and destroyed our shrines and palaces and took our people up to Egypt. Oh, it was desolate, and I shed many tears, for I missed the busy hum of the market and the merry voices of the children.

“But come with me, little Annabelle, I will show you all this, the rich past of the Ethiopian.”

She bade the little girl take hold of her hand and close her eyes, and wish herself in the wood behind the cornfield. Annabelle obeyed, and ere they knew it they were sitting beside the clear water in the pond.

“You should see the Niger,” said the fairy. “It is still beautiful, but not as happy as in the old days. The white man’s foot has been cooled by its water, and the white man’s blossom is choking out the native flower.” And she dropped a tear so beautiful the costliest pearl would seem worthless beside it.

“Ah! I did not come to weep,” she continued, “but to show you the past.”

So in a voice sweet and sad she sang an old African lullaby and dropped into the water a lotus leaf.[5] A strange mist formed, and when it had disappeared she bade the little girl to look into the pool. Creeping up Annabelle peered into the glassy surface, and beheld a series of vividly colored pictures.

First she saw dark blacksmiths hammering in the primeval forests and giving fire and iron to all the world. Then she saw the gold of old Ghana and the bronzes of Benin.[6][7] Then the black Ethiopians poured down upon Egypt and the lands and cities bowed and flamed. Next she saw a great city with pyramids and stately temples. It was night, and a crimson moon was in the sky.[8] Red wine was flowing freely, and beautiful dusky maidens were dancing in a grove of palms. Old and young were intoxicated with the joy of living, and a sense of superiority could be easily traced in their faces and attitude. Presently red flame hissed everywhere, and the magnificence of remote ages soon crumbled into ash and dust. Persian soldiers ran to and fro conquering the band of defenders and severing the woman and children. Then came the Mohammedans and kingdom on kingdom arose, and with the splendor came ever more slavery.[9]

The next picture was that of a group of fugitive slaves, forming the nucleus of three tribes, hurrying back to the wilderness of their fathers.

In houses built as protection against the heat the blacks dwelt, communing with the beauty of water and sky and open air. It was just between twilight and evening and their minstrels were chanting impromptu hymns to their gods of nature. And as she listened closely, Annabelle thought she caught traces of the sorrow songs in the weird pathetic strains of the African music mongers.[10] From the East the warriors of the tribe came, bringing prisoners, whom they sold to white strangers from the West.

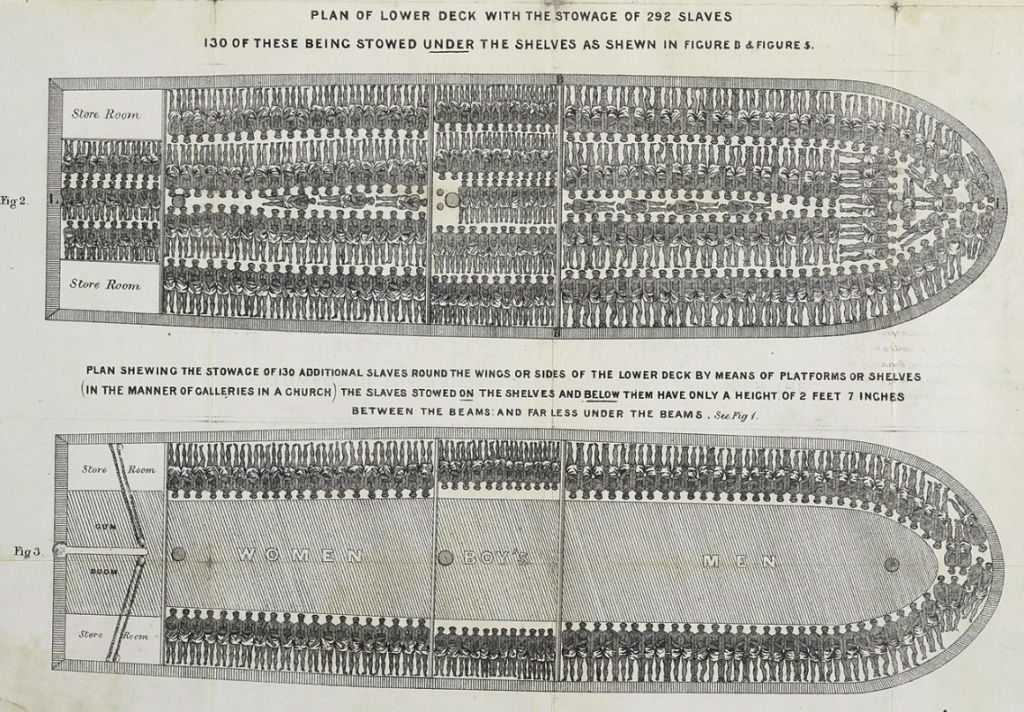

“It is the beginning,” whispered the fairy, as a large Dutch vessel sailed westward.[11] Twenty boys and girls bound with strong ropes were given to a miserable existence in the hatchway of the boat. Their captors were strange creatures, pale and yellow haired, who were destined to sell them as slaves in a country cold and wild, where the palm trees and the cocoanut never grew and men spoke a language without music. A light, airy creature, like an ancient goddess, few before the craft guiding it in its course.

“That is I,” said the fairy. “In that picture I am bringing your ancestors to America. It was my hope that in the new civilization I could build a race that would be strong enough to redeem their brothers. They have gone through great tribulations and trials, and have mingled with the blood of the fairer race; yet though not entirely Ethiopian they have not lost their identity. Prejudice is a furnace through which molten gold is poured. Heaven be merciful unto all races! There is one more picture –the greatest of all, but –farewell, little one, I am going.”

“Going?” cried Annabelle. “Going? I want to see the last picture—and when will you return, fairy?”

“When the race has been redeemed. When the brotherhood of man has come into the world; and there is no longer a white civilization or a black civilization, but the civilization of all men. I belong to the world council of the fairies, and we are all colors and kinds. Why should not men be as charitable unto one another? When that glorious time comes I shall walk among you and be one of you, performing my deeds of magic and playing with the children of every nation, race and tribe. Then, Annabelle, you shall see the last picture—and the best.”

Slowly she disappeared like a summer mist, leaving Annabelle amazed.

JOHNSON, FENTON. “THE BLACK FAIRY,” THE CRISIS 6, NO. 6 (OCTOBER 1913): 292-94.

[1] The establishment of black colleges and graduate schools during the Reconstruction Era (1865-1877) allowed the emergence of a new class of black professionals. The Howard School of Law, established on January 4, 1869, was the first black law school in America. Macon Bolling Allen (1816-1894), however, is believed to be the first African American licensed lawyer. He received his certification on July 3, 1844.

[2] The following excerpt from W. E. B. Dubois’s 1903 landmark The Souls of Black Folk, in which he partially outlines the influential concept of double-consciousness, may contextualize Fenton Johnson’s allusion to the Seventh Veil:

“After the Egyptian and Indian, the Greek and Roman, the Teuton and Mongolian, the Negro is a sort of seventh son, born with a veil, and gifted with second-sight in this American world,”a world which yields him no true self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself thought the revelation of the other world.”

[3] With a length of 2,600 miles, the Niger River is the main river of Western Africa and the third longest African river after the Nile and the Congo.

[4] The sacred beetle refers to the Egyptian scarab, a dung beetle that for the ancient Egyptians symbolized renewal and rebirth. This beetle was also associated with Khepri, a divine manifestation of the early morning sun.

[5] Tigit Shibabaw‘s interpretation of Eshururu, an Ethiopian lullaby in Ahmaric, an Ethiopian Semitic language. “Eshururu” means “hush little baby don’t you cry.”

[6] As of today, Ghana remains a leading producer of gold in Ghana and is the seventh gold producer in the world. Unregulated small-scale gold mining in this country are a current environmental concern due to its devastating effect on the landscape.

[7] The “Benin Bronzes” are brass-and-bronze sculptures whose creation dates back to the 16th century. In 1897, British soldiers looted hundreds of these objects from the Benin Royal Palace after a military expedition that effectively ended the independent Kingdom of Benin. The same year, the British Museum displayed a set of “Benin Bronzes” that together with later acquisitions from private collections still remains in the museum’s collection. In October 2021, the British Museum received a request from Nigeria’s Federal Ministry of Information and Culture for the return of Nigerian antiquities. Representatives from the Benin Royal Palace have also asked publicly for the restitution of these looted art objects.

[8] “Crimson moon” and “blood moon” are non-scientific terms for a total lunar eclipse, during which the moon takes on a reddish color.

[9] Mohamedans are followers of Muhammad, the Islamic prophet. In the XVI century, Islamic forces led by Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi invaded Ethiopia.

[10] Sorrow Songs (or spirituals) belong to the musical tradition of black slaves during the antebellum South.

[11] Between 1596 and 1839, the Dutch, active participants in the transatlantic slave trades, transported half a million Africans westward across the Atlantic.

Contexts

Starting in 1912, the October issues of The Crisis, the official magazine of the NAACP, were dedicated to children. A typical edition of these children’s numbers would contain a special editorial piece and two or three literary works specifically for children, while still including the serious pieces about contemporary issues with a focus on race that The Crisis was known for. These October numbers were sprinkled with children’s photographs sent in by the readers.

In his first editorial for the Children’s number in 1912, W. E. B. Du Bois wrote that “there is a sense in which all numbers and all words of a magazine of ideas myst point to the child—to that vast immortality and wide sweep and infinite possibility which the child represents.”

The success of The Crisis’ children’s number led to the standalone The Brownies’ Book, a monthly magazine for African American children that circulated from January 1920 to December 1921 under the editorship of Du Bois, Augustus Granville Dill, and Jessie Fauset.

Fenton’s Johnson’s “The Black Fairy” also appeared in The Upward Path: A Reader for Colored Children in 1920.

Definitions from Oxford English Dictionary:

crimson: Of a deep red colour somewhat inclining towards purple.

hist: Used to enjoin silence, attract attention, or call on a person to listen.

Resources for Further Study

- Ethiopianism, a literary-religious tradition that emerged during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, emphasized the classical values of African nations and their extensive histories before European colonization. In the United States, Ethiopianism “found expression in slave narratives, exhortations of slave preachers, and songs and folklore of southern black culture, as well as the sermons and political tracts of the urban elite.”

- A brief history of fairies, courtesy of the World History Encyclopedia collective.

- An article on fairies‘ folklore scholarship, with copious references and suggestions for further reading.

- Kory, Fern. “Once upon a Time in Aframerica: The ‘Peculiar’ Significance of Fairies in the Brownies’ Book.” Children’s Literature, vol. 29, 2001, p. 91-112.

Contemporary Connections

Did you know that June 24th is International Fairy Day?

Louis Armstrong’s interpretation of “Go Down Moses,” an emblematic Sorrow Song.