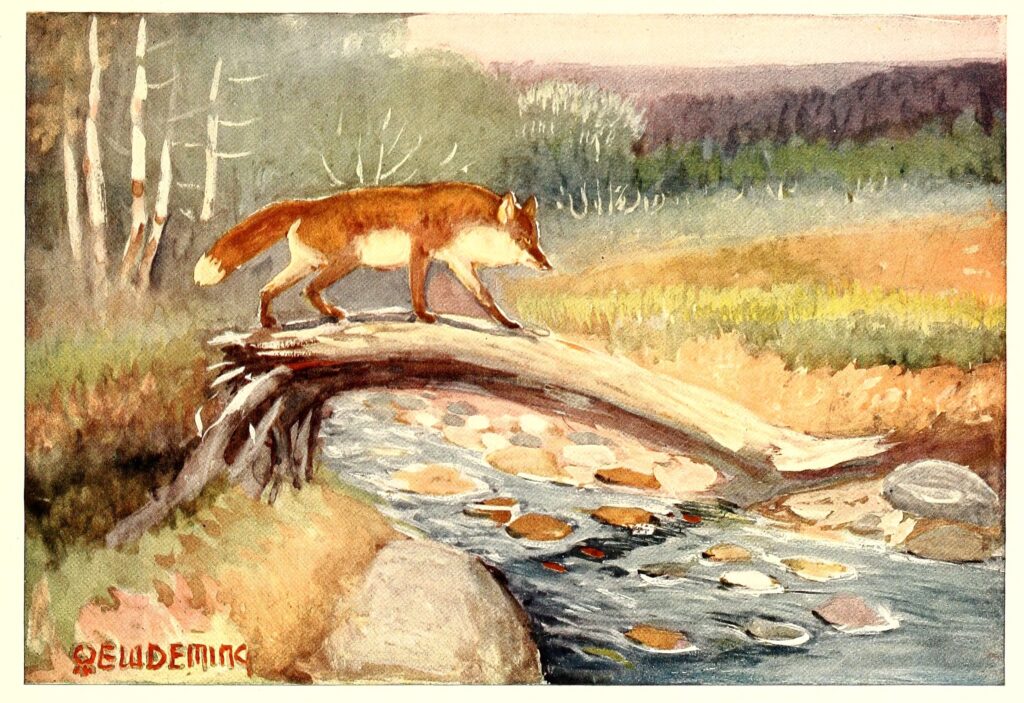

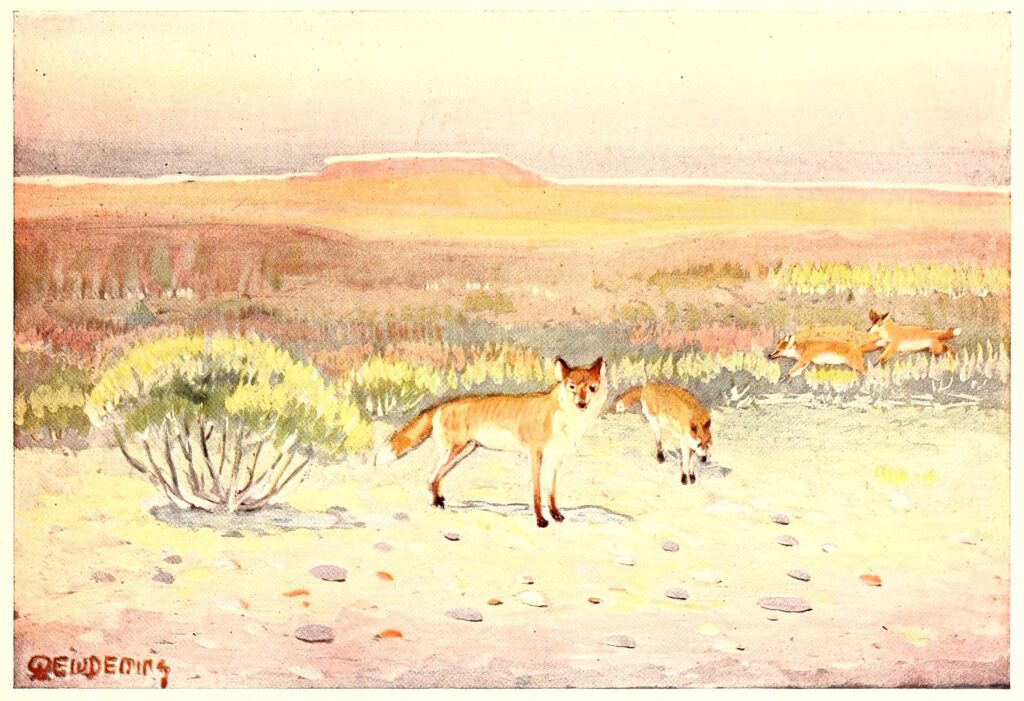

Red Fox and Cotton Tail

By Therese Osterheld Deming

Annotations by Rene Marzuk

R

ed fox is one of the wisest and most cunning of little creatures, with so little feat of man that he prefers to live neat settlements, where he can poach upon the farmer’s chickens and fowl to help out his menu of mice and rabbits, birds and other wood folk.[1]

The foxes make dens in the midst of big tree forests, or in crevices among the rocks, where the vixen (mother) hides her four of five cubs while she goes out to find food to bring home. She always travels in a roundabout way, to and from her den, so that her enemies cannot find the way. She never leaves any refuse about her doorway that might attract the attention of man or animal folk who may be hunting about her domain.[2]

On sunny days the vixen takes her fox cubs out into the sunshine to play. They may never have seen man, yet they run and hide at his approach; but if caught, they make very lovely little pets.

Some friends, hunting in New Brunswick, caught a little fox cub and put him into a box cage.[3] They shot Canadian jays for their little captive, and the cunning little fellow carried each on into his box to hide it, until he had his box so full that he could not get into it himself. He became very tame and played all day; but at night the hunters would awaken to hear his plaintive little bark, then off in the distance would come the answer comr the poorl old vixen, who was mourning the loss of her little one, while the screech-owl flew from limb to limb, seeming to laugh at the troubles of the poor mother trying to quiet her lost one.

During the nesting season, the red fox destroys quantities of quail and partridge nests. He is hunted with hounds and seems to enjoy the sport as much as his pursuers, leading them a merry chase, often running the top rail of a fence or jumping from stone to stone. Should he get far ahead, he will stop and wait for the hounds to catch up, then off he runs again and often gets away finally, to hide and rest in his den. If he should suddenly come upon a hunter, he will show no signs of fear, but just pretend he never saw him, and gradually work away until he is over some small hill, then he will run as fast as he can, to get out of the way.

He is the handsomest and most valuable fox from the Southern Alleghanies to Point Barrow, wearing many different suits in different parts of the country, from yellow-red to the palest of bleached-out colors on the sun-kissed desert, and very bright colors in the forest regions of Alaska.

He is so cunning and so well able to care for himself that it is not so easy to exterminate him as it is other animals less wise.

The black-cross fox and the silver fox are just two different phases of the same red fox.

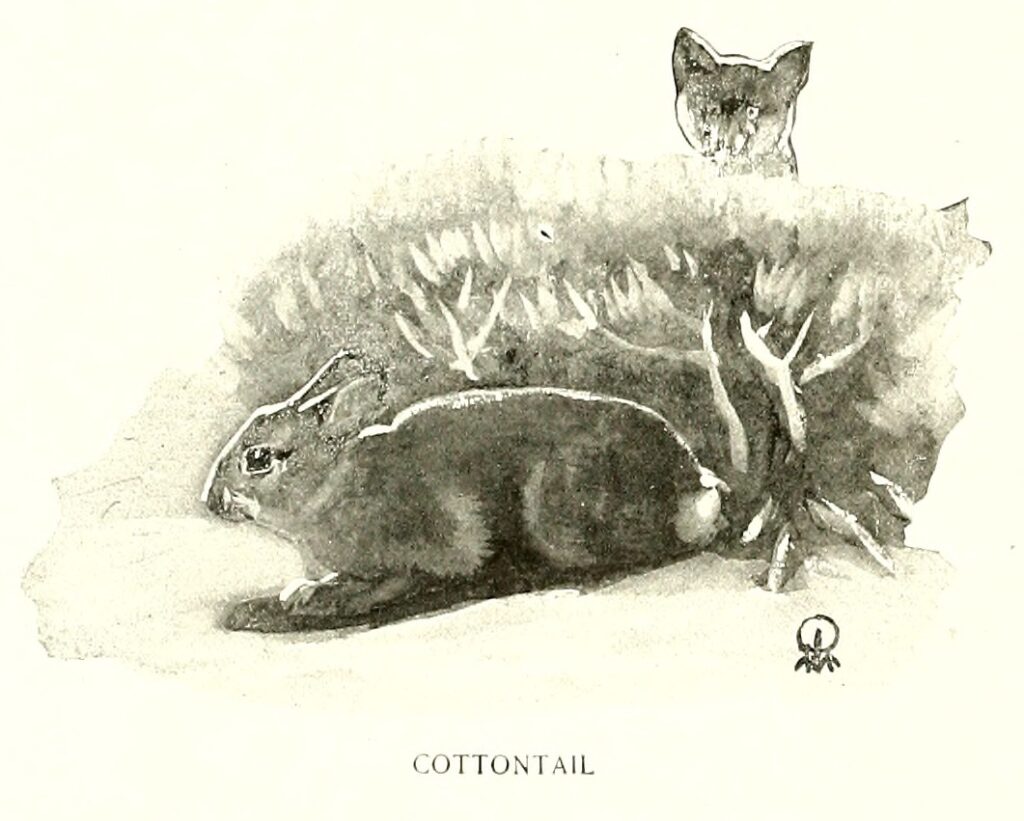

The red fox has a very keen sense of hearing. He depends more upon his ears and nose than upon his eyes in detecting the approach of danger or in locating his prey. When he gets scent of a rabbit, he is happy: for rabbits are his favorite food, and poor little molly-cottontail must always be watchful or she will be caught. Should she not see her enemy until he is almost upon her, she will lie very close to the ground, behind a bunch of grass or a bush, and never move. Often the hunter will pass her by; but sometimes she has a hard run to save her life, and many times. poor thing, she is caught.

The cottontail is the smallest of the rabbit family and is found all over the country. She burrows in the ground for a home; but, unfortunately, she has not learned to make herself a back door, to escape in time of danger, for members of the weasel or marten families follow this creature into her home.

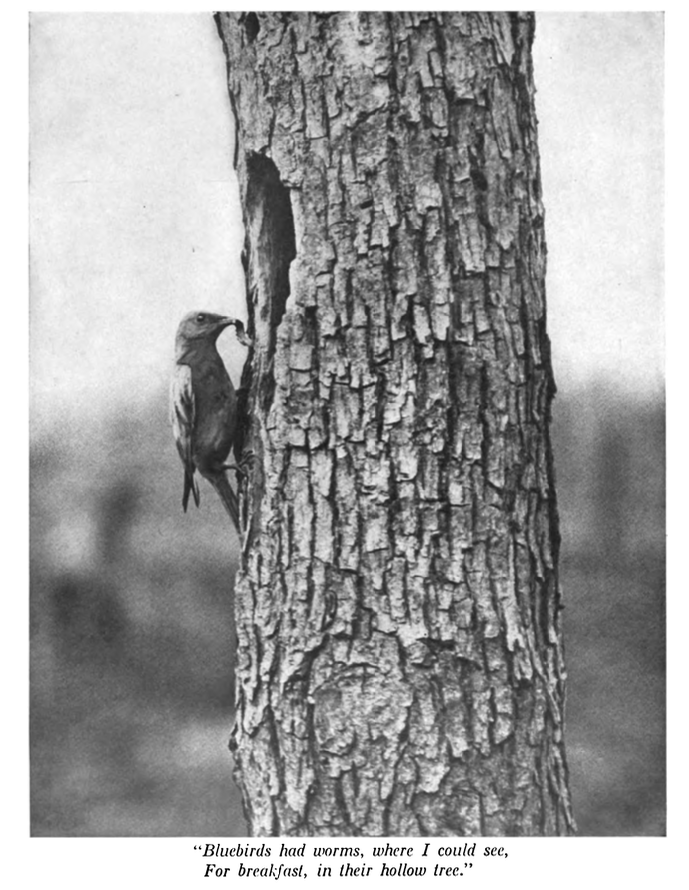

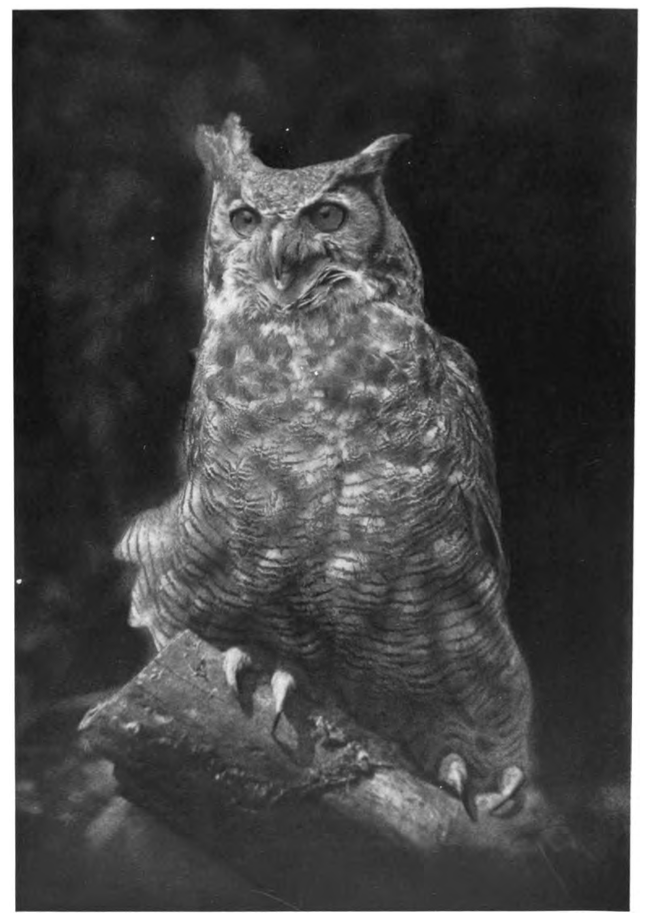

Like all rabbits she has regular runways or trails through the woods; but on moonlight nights she will come out into the clearings, with her relatives, and romp, play and frisk about in the moonlight, having a lively time. Suddenly one of the brothers will stamp his feet, and in a second all have disappeared and run for safety. Most people might have wondered what the matter was. Little Brother Rabbit knew, for almost instantly, Ko-Ko-Kas, the big brown owl, flew over the clearing and each little rabbit was glad he had heard and obeyed the warning. Had he not he would have suffered more than when Chief Rabbit refused to go to a council called by Owl. Owl was chief then, and called four times, but the Rabbit did not answer. Then he told the Rabbit his ears would grow until he came to the council. We all know how long his ears grew; and they might have been much longer had not the Rabbit answered and run to the council as fast as he could go.

DEMING, THERESE OSTERHELD. “RED FOX AND COTTON TAIL,” IN AMERICAN ANIMAL LIFE, 67-76. NEW YORK: FREDERICK A. STOKES, 1916.

[1] In addition to rodents, rabbits, birds, and amphibians, the diet of red foxes also includes fruit.

[2] Interestingly, red foxes rarely sleep in their dens, but out in the open. They will only sleep in their burrows during extreme weather or, in the case of female foxes, while raising their kits.

[3] New Brunswick is a province of Canada.

Contexts

American Life is one of a series of books written by Therese Osterheld Deming and illustrated by Edwin Willard Deming. After marrying in 1892, the Demings frequently worked together. Edward Willard Deming was an American painter and sculptor who, after studying in Paris in 1884 and 1885, lived in proximity to various Indigenous American tribes. These experiences informed most of his work.

Resources for Further Study

- Learn more about Edwin Willard Deming.

Contemporary Connections

What to do if you see a fox in your neighborhood.