The Yellow Tree

By DeReath Byrd Busey

Annotations by Rene Marzuk

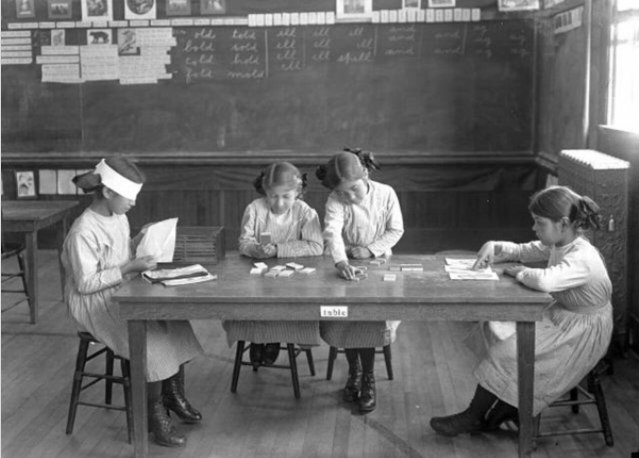

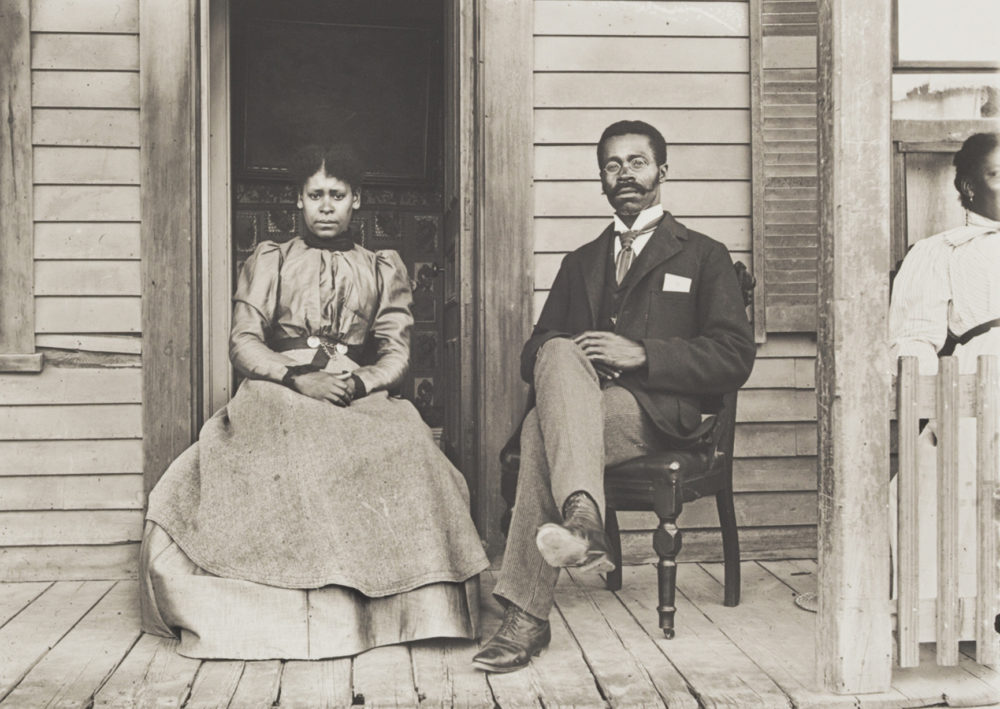

Plum Street is a firm believer in “signs.” It is not an ordinary street—not even physically, for it begins at Ludlow, stops on Clark where the trolley passes, picks itself up a half block south on Clark and rushes across the railroad straight uphill to the Fair Grounds. In the early nineties it was the thoroughfare for the “southend,” but Jasper Hunley, who bought Lester Snyder’s house at public auction, proved to be a “fair” Negro. Then the Exodus![1] In 1919 Negroes had been in undisputed possession for twenty years.[2]

Like the colors of their faces, the houses vary. There is Jasper Hunley’s big brown house with built-in china cabinet and bookcases, hardwood floors and overstuffed furniture. On either side of him in white houses live the Reverend Burns and Policeman Jenkins in a little less state, with portable furniture sparsely upholstered, and carpets. Across the street lives Mother Stewart and Reverend Gordon in plain barefaced houses with scarred pine furniture.

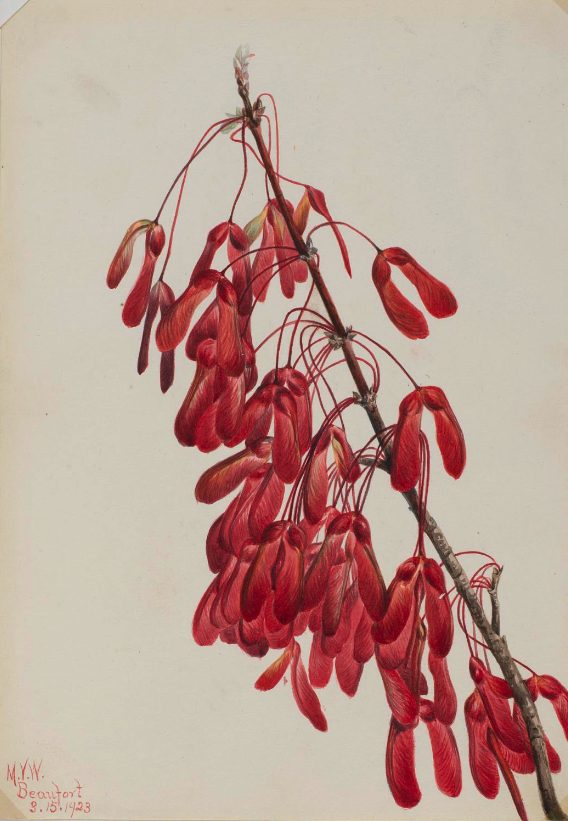

At the close of the January day, Mary Hunley sat watching at her window for Eva Lou’s home-coming from the office. Again she recalled vividly the June day she had sat with bed-ridden Mother Stewart while Lucy went to market. She had been sitting at the second story window feasting her eyes upon her hardwon home across the street—a big house in a big yard with flowers and young trees in spring garb. The roses were beginning to open. She had smiled contentedly as her eyes lingered on each bush and shrub but a puzzled frown crossed her brow as she noticed her youngest maple had yellowed. She wondered if worms were at its root.

She turned her eyes to gaze down at the Reverend Mr. Gordon, who pulled his broad brimmed hat further over his eyes, squared himself on his bare board bench in the corner of the yard and sank into a revery. Unpainted palings enclosed the tiny grassless yard about his unpainted weather-stained house, distinguished from its neighbors only by a bright blue screen door. The Reverend, tall, broad, his brown face growing darker with age, had lived on Plum street ever since he had been called from the janitorship of the Mecklin Building to the pastorate of the St. Luke’s Baptist Church. He had come to be the oracle of the street.

His dreams were respectfully broken by the greetings of returning marketers. Mary listened idly until Lucy stopped for a conversation. They spoke of the movies and the man there to whom the whole town was flocking for advance information on the future. Lucy thought his amazing replies all a trick. Mr. Gordon concurred.

“Yet,” he said, “the Lawd do give wahnin’ of things t’come t’them that believes, Miss Lucy. Ah’m not a-tall supstitious but when ah gits a sign ah knows it.”

“Yassuh,” Lucy nodded.

“Las’ yeah,” he continued, “ah says to Mrs. Reveren’ Burns that somebody in that house on the cornuh o’ Clark would die ‘fore spring come agin. She laffed. In Feb’uary the oldest boy died o’ consumption. The new leaves on d’tree in d’front yahd turned yeller. When a tree does that, Miss Lucy, death comes in the fam’ly fore a yeah is gone.”

He paused portentously. Mary Hunley leaned unsteadily closer to the window. He spoke solemnly as he pointed his long finger.

“That tree yonde’ in Jasper Hunley’s yahd turned yeller las’ night. This is June, Miss Lucy. The Lawd do give wahnin’s to them as believes.”

Mary Hunley never knew how she got home. She only knew the Lord had sent her warning. She had always believed in signs—and the few times she had ignored them they had told truth with a vengeance.

When but a girl a circus fortune-teller had drawn a picture of her future husband who should bring money and influence. When Jasper Hunley, carpenter, came a-wooing, his likeness to the picture made the match. She never really loved him, but he was her Fate so they married.

The first year of her marriage she dreamed three nights that they had moved into a big brown house. When Lester Snyder went bankrupt—Jasper bought the house. They moved in and their neighbors moved out. Racial gregariousness was stronger than economy, so houses went for a song.[3] Enough of them came to Jasper to make him potential potentate of Plum street. But Jasper was slow, not given to show, and contented to be hired.

Mary came to realize that he would only bring the money. She must make the influence. She had received diploma and inspiration from one of those Southern Missionary Schools for colored youth, and she had thoroughly imbibed “money and knowledge will solve the race problem.” [4] In ten years she had made Jasper a contractor. She read, she joined “culture clubs,” she spoke to embroidery clubs on suffrage when it was a much ridiculed subject, she managed Jasper’s business, drew up his contracts, and still found time to keep Eva Lou the best dressed child in Plum street school.

On Plum street as in some other Negro communities color of skin is a determining factor in social position.[5] Mary had cared for that. Jasper was fair and she became fair. From the days of buttermilk and lemon juice to these of scientific “complexion beautifier” she kept watch on herself and Eva Lou.[6] When Eva Lou came back from school in Washington she was whiter and more fashionable than ever; the street wondered, envied, resented.

Gradually Mary grew to feel that the glory of her ambition would come through her daughter. She centered all her love and energies upon Eva Lou—the promise and fulfillment of her life. Occasionally she thought Eva Lou indiscreet in bringing city fashions among small town people, yet she trusted her to have learned on her expensive trips what the great world does. Eva Lou and a few kindred spirits who had ventured far afield—to Chicago and Washington, Boston and New York—had established a clique of those who wore Harper’s Bazaar clothes unadulterated, smoked cigarettes in semi-privacy, and played from house to house. Plum street’s scandalized gossip joyfully reported by Lucy she ascribed to envy. Lucy, black and buxom, hated Eva Lou’s lithe pallor. Mary smiled. Only those in high places are envied.

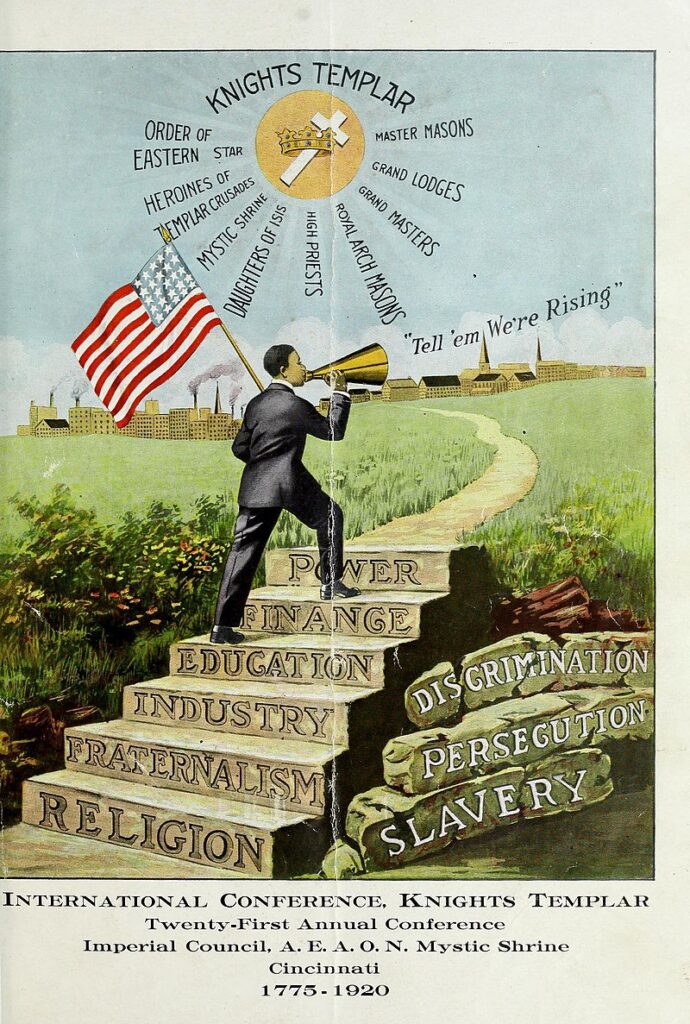

That June morning as she sat at Mother Stewart’s window, she had breathed a sigh of relief. At last, she could relax. Jasper was a thirty-third degree Mason and Eva Lou was engaged to Sargeant Hawkins of Washington.[7]

Then Gordon’s prophecy smashed in upon her soul. For one panic stricken hour she was filled with terror. But the qualities that had fought for her family for twenty-five years came to her rescue. She knew the prophecy was of Eva Lou. And she who had believed implicitly and fearfully set out to give that yellow tree the lie. She shuddered with dread but she would not retract.

“If I tell Babe,” she reasoned, “wor’y will make her sick. I’ll just have to fight it out alone.”

January was here now. Never a winter before had Eva Lou been so plagued with good advice and flannels. At first she had listened civilly but unheedingly. Finally she firmly refused both. She wore as many as she needed. As for spats and rubber—

“Well, I’ll say not. Pumps ah the thing this wintuh. An’ what if I do cough! Ev’rybody’s got a cold this weathuh. You have yuhself.”

Daily tears did not move her. Fear and a hacking cough were breaking the splendid courage of Mary. Plum street, informed by Lucy, waited the prophecy’s fulfillment in sympathetic certainty.

Down the street Mary saw Dr. Dancey’s car come slowly rolling. She had heard him say flu and pneumonia were rampant again. Suppose Eva should get either! She could not recover. That yellow tree would win and life come crashing to her feet.

“I’ll just have to take care of myself and get rid o’ this grip I have—”[8]

Dr. Dancey was stopping at her door and helping Eva Lou alight.

“O Babe!” Mary cried as she dragged her unwilling body to the door and snatched it open. “Babe, are you sick? Are y’sick?”

Dr. Dancey tried to quiet her. Eva Lou had an attack of grip—nothing more. A hot bath, hot drink, and long night’s sleep would set her right. Mary knew he lied. Grip did not make you look as Babe did. Mary knew for days that the aching limbs and throbbing head she had were signs of grip. When she asked Babe she said she just felt weak.

After Jasper and Eva Lou were asleep, Mary lay in bed and racked her fevered brain for means to thwart the threatening evil. Ah—the sure solution shone clear before her. Her tortured mind felt free and calm. A smile of cunning triumph crept over her face. She eased out of bed, slipped on her flannelette kimono and bedroom slippers. She crept in to look at Babe. She stared, then stooped and kissed the girl’s hot lips. Sweet little Babe! Mother would save her. She raised her head and smiled in calm defiance across the sleeping girl at the shrouded figure of the waiting Death Angel near the window. Not yet would it get her!

She smiled with cunning triumph again at the silent figure. Why didn’t it move? She knew. It was sorry. It had come in vain.

Down the back stairs and into Jasper’s tool room she floated. All pain had left her. Her thinking was clear and her body light as air. As she bent over the tool box she chuckled. She had never felt so certain of success since the day she married Jasper. Softly she drew out the bright, keen saw. In the kitchen she stopped for salt to sprinkle on the ice. She might slip. She floated around the house and to the youngest maple. Carefully she anointed its ice covered trunk and limbs with salt. Every crackle of the melting ice brought joy to her heart. When she felt a bare wet space on the tree she began sawing—haltingly, unrhythmically. Over and over she whispered exultantly.

“The yellow tree lied! The yellow tree lied!”

Once she stopped to wonder why she was not cold, but she was so light and warm it seemed a waste of time. Not even her feet were cold.

The saw was almost through the tree. She raised herself to gloat over its fall.

But it was not a tree. It was that same Angel of Death. The laugh froze in her throat. His face was uncovered and he was smiling. He swayed toward her once —twice. Suppose he should rush over her and get Babe anyway! She laughed now— sweet, carefree. She still would win. She would hold him—if it were forever. The Angel swayed again and fell into her outstretched arms. They held each other.

Early in the morning slow moving Jasper found her there on the ice with the tree over her.

They buried her yesterday. Eva Lou wore white mourning. Lucy, voicing the query of Plum street, asked Reverend Gordon why the yellow tree took the wrong one.

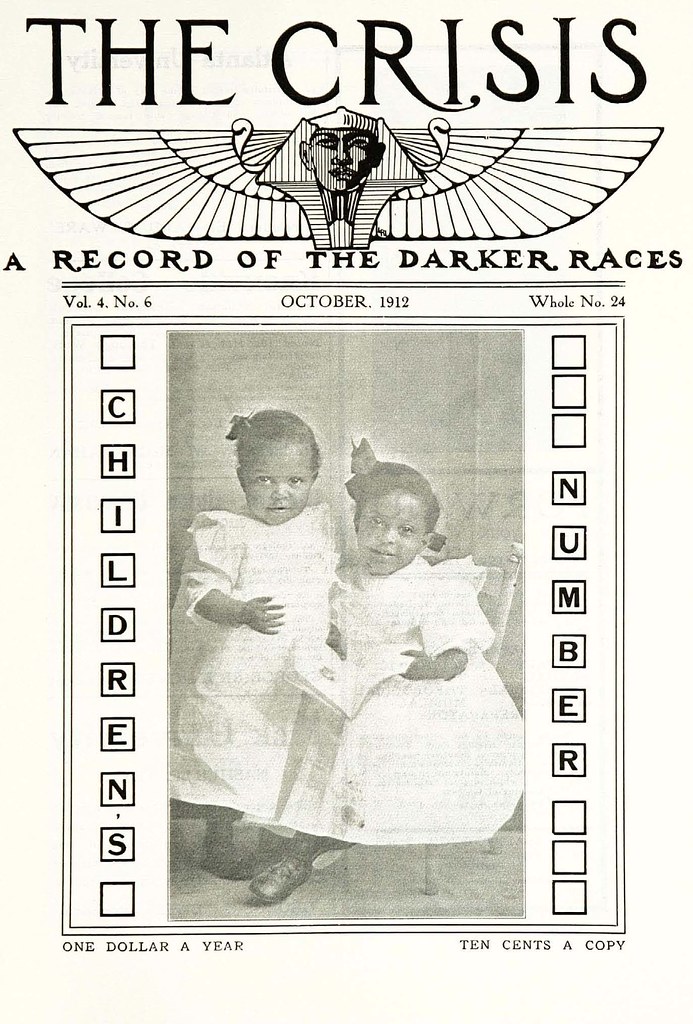

BUSEY, DEREATH BYRD. “THE YELLOW TREE: A STORY.” THE CRISIS 24, NO. 6 (OCTOBER 1922): 253-56.

[1] A likely reference to the Great Migration (1910-1970), one of the largest movements of people within the United States. Almost six million African American southerners moved to Northern, Midwestern, and Western states to escape racial violence and pursue better opportunities.

[2] In the year 1919, a particularly brutal outburst of violence against African Americans across the United States became what we know now as the Red Summer.

[3] “White flight,” which refers to the movement of white city residents to the suburbs to escape the influx of minorities, explains why racial gregariousness would have caused house prices to drop in African American neighborhoods. Redlining and blockbusting promoted a wave of “white flight” to the suburbs after World War II; however, a new study suggests that “white flight” really started during the first decades of the twentieth century.

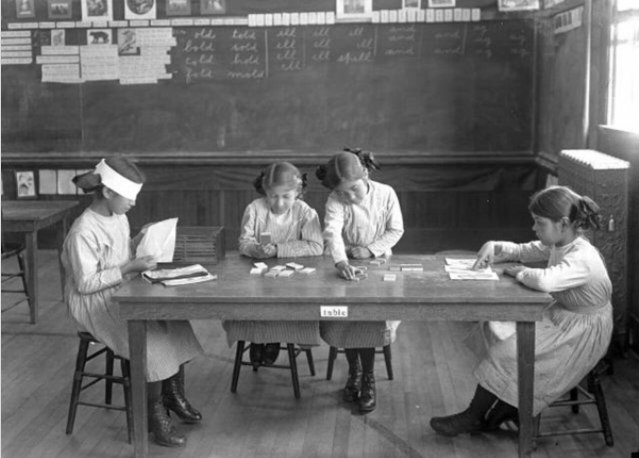

[4] During Reconstruction (1863-1877), missionary societies and African Americans established over 3,000 schools in the South for the pubic education of freedmen.

[5] Colorism, which refers to the prejudice against dark skin, is prevalent within African American communities.

[6] In her essay “Black No More: Skin Bleaching and the Emergence of New Negro Womanhood Beauty Culture,” Treva B. Lindsey connects the popularity of bleaching products and procedures in African American communities during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to “perceived and real desires for social mobility and aesthetic valuation within a cultural hierarchy premised upon white cultural supremacy.”

[7] Jasper Hunley probably belonged to the Prince Hall Masons, a Masonic lodge for African American men that dates back to 1787. Due to racism and segregation, African Americans could not join most Masonic lodges until the late twentieth century. The thirty-third degree is an honorary Masonic degree.

[8] The grip is a common name for epidemic influenza (flu).

Contexts

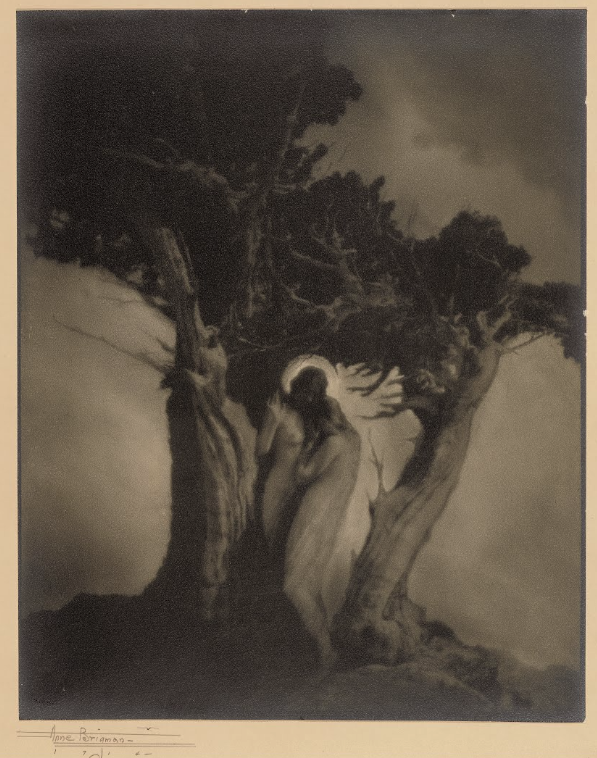

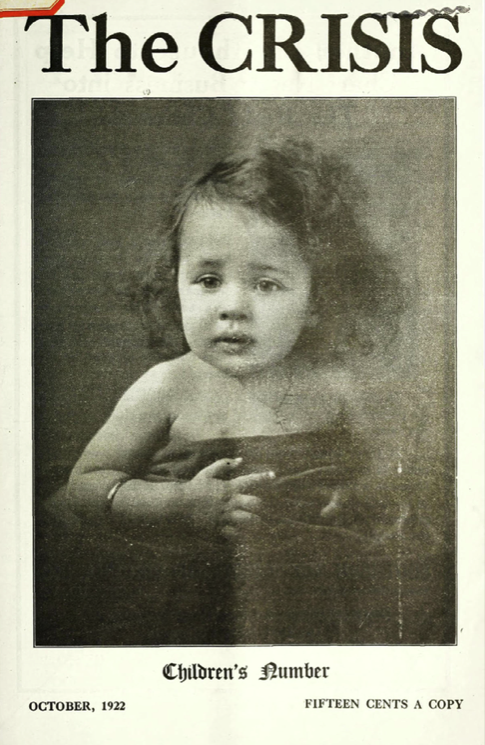

Starting in 1912, the October issues of The Crisis, the official magazine of the NAACP, were dedicated to children. A typical edition of these children’s numbers would contain a special editorial piece and two or three literary works specifically for children, while still including the serious pieces about contemporary issues with a focus on race that The Crisis was known for. These October numbers were sprinkled with children’s photographs sent in by the readers.

In his first editorial for the Children’s number in 1912, W. E. B. Du Bois wrote that “there is a sense in which all numbers and all words of a magazine of ideas myst point to the child—to that vast immortality and wide sweep and infinite possibility which the child represents.”

The success of The Crisis’ children’s number led to the standalone The Brownies’ Book, a monthly magazine for African American children that circulated from January 1920 to December 1921 under the editorship of Du Bois, Augustus Granville Dill, and Jessie Fauset.

According to the Early Black American Playwrights and Dramatic Writers: A Biographical Directory and Catalog of Plays, Films, and Broadcasting Scripts, in the same year The Crisis published “The Yellow Tree” Irene DeReath Busey adapted her short story into a dramatic play produced by the Howard University Players in Washington, DC.

Definitions from Oxford English Dictionary:

exodus: The departure or going out, usually of a body of persons from a country for the purpose of settling elsewhere. Also, the title of the book of the Old Testament which relates the departure of the Israelites out of Egypt.

for a song: For a mere trifle, for little or nothing.

thoroughfare: A passage or way through.

Resources for Further Study

- Shertzer, Allison, and Randall P. Walsh. “Racial Sorting and the Emergence of Segregation in American Cities.”

- Craig, Maxine Leeds. “Black women and Beauty Culture in 20th-Century America.”

Contemporary Connections

Coates, Ta-Nehisi. “The Case for Reparations.”

Greenidge, Kaitlyn. “Why Black People Discriminate Among Ourselves: The Toxic Legacy of Colorism.”

Hall, Ronald. “Women of Color Spend More Than $8 Billion on Bleaching Creams Worldwide Every Year.”