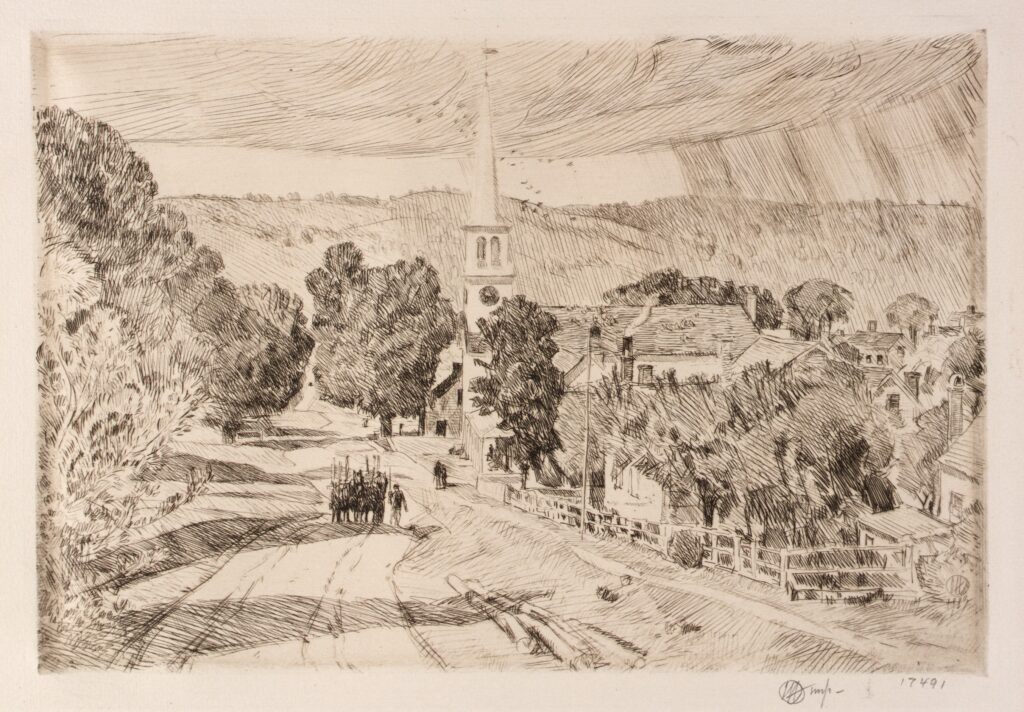

The Talk of the Trees that Stand in the Village Street

By Jane Andrews

Annotations by Josh benjamin

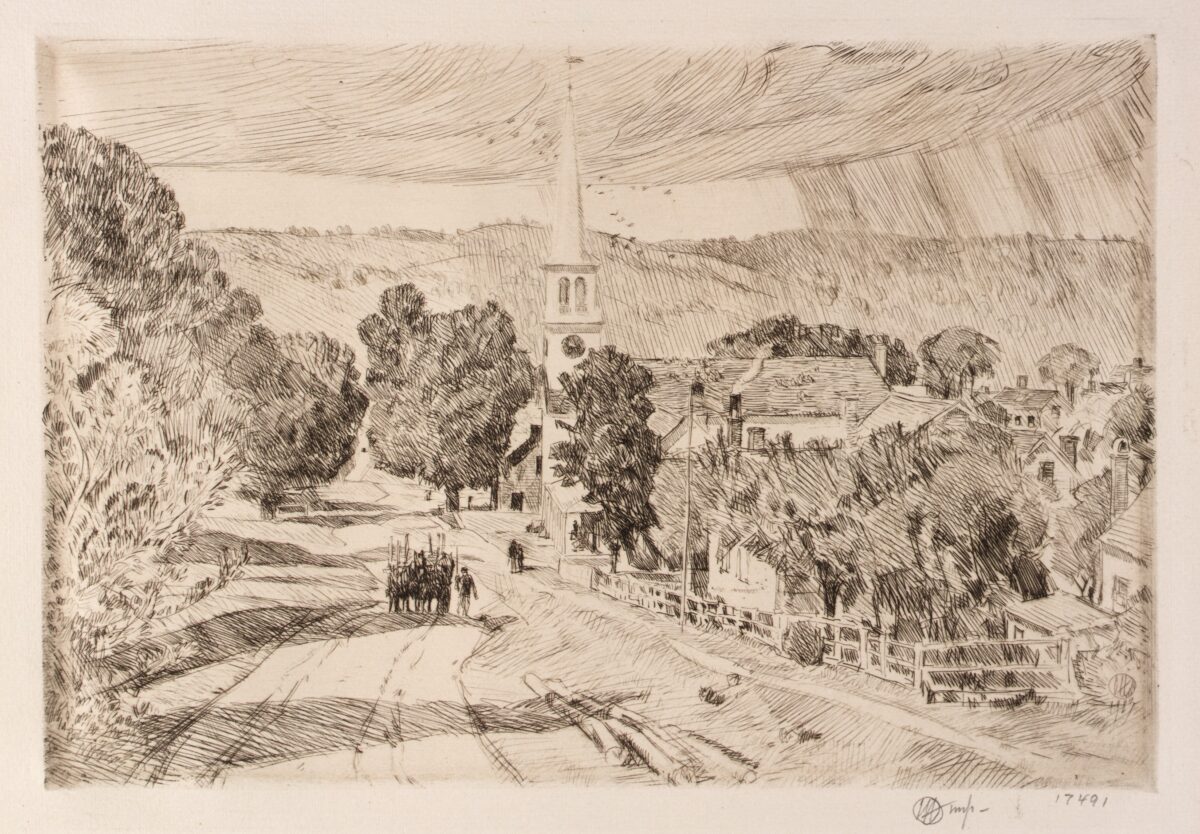

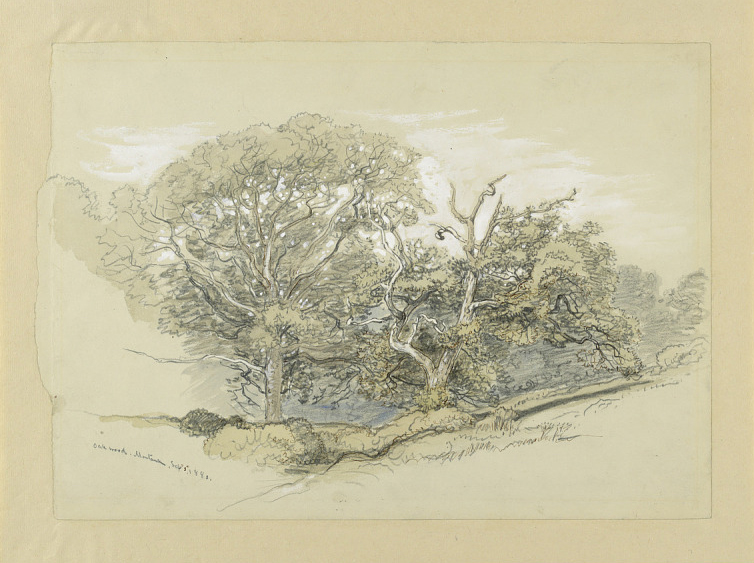

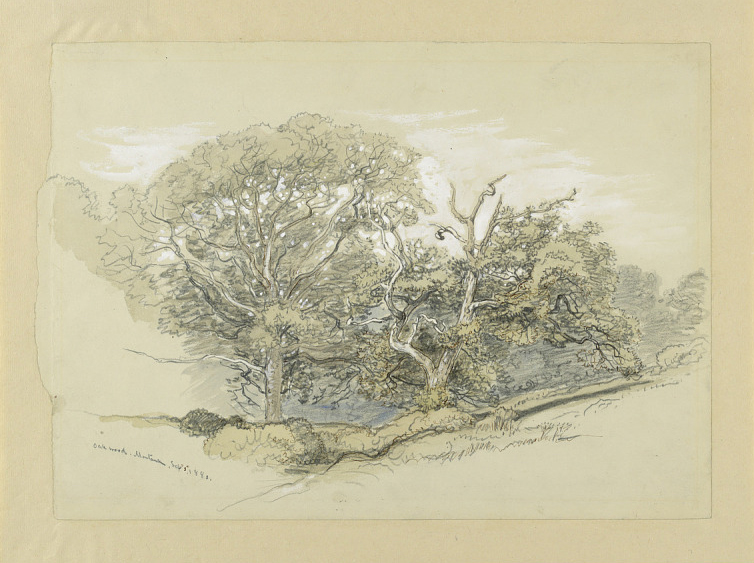

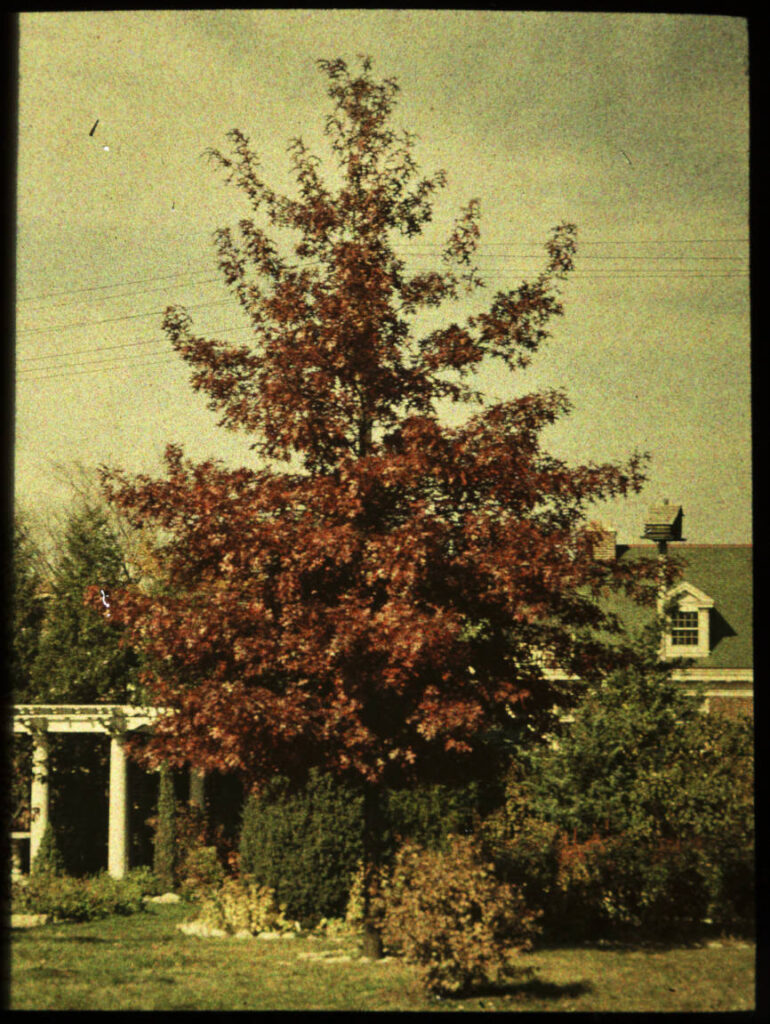

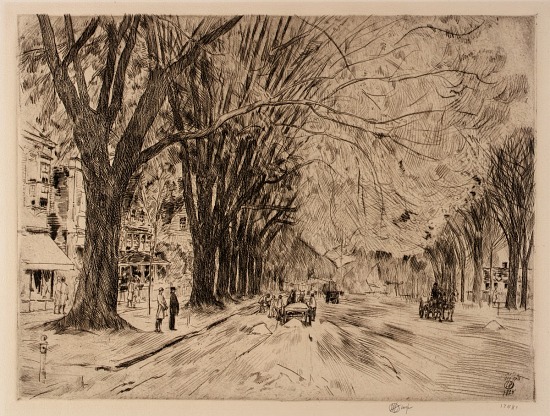

HOW still it is! — nobody in the village street; the children all at school, and the very dogs sleeping lazily in the sunshine; only a south wind blows lightly through the trees, lifting the great fans of the horse-chestnut, tossing the slight branches of the elm against the sky, like single feathers of a great plume, and swinging out fragrance from the heavy-hanging linden-blossoms.

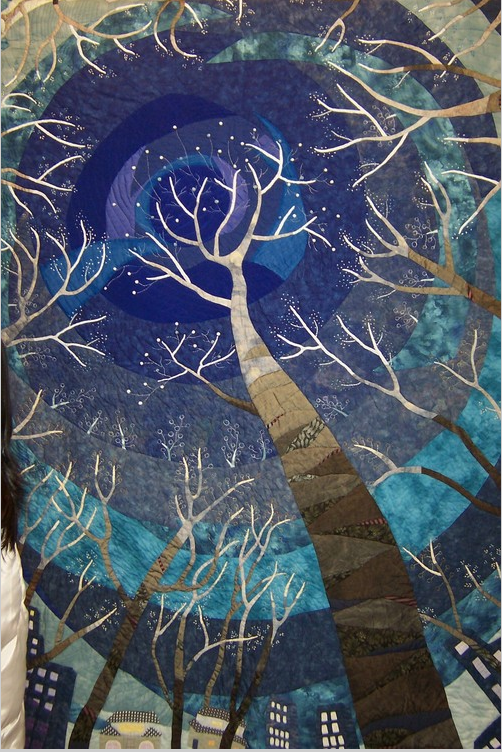

Through the silence there is a little murmur, like a low song; it is the song of the trees; each has its own voice, which may be known from all others by the ear that has learned how to listen.

The topmost branches of the elm are talking of the sky, — of those highest white clouds that float like tresses of silver hair in the far blue, — of the sunrise gold and the rose-color of sunset, that always rest upon them most lovingly. But down deep in the heart of the great branches, you may hear something quite different, and not less sweet.

“Peep under my leaves,” sings the elm-tree, “out at the ends of my broadest branches. What hangs there so soft and gray? Who comes with a flash of wings and gleam of golden breast among the dark leaves, and sits above the gray hanging nest to sing his full sweet tune? Who worked there together so happily all the May-time, with gray honeysuckle fibres, twining the little nest, until there it hung securely over the road, bound and tied and woven firmly to the slender twigs, — so slender, that the squirrels even cannot creep down for the eggs, much less can Jack or Neddy, who are so fond of bird’s-nesting, ever hope to reach the home of our golden robin?

“There my leaves shelter him like a roof from rain and from sunshine. I rock the cradle when the father and mother are away, and the little ones cry, and in my softest tone I sing to them; yet they are never quite satisfied with me, but beat their wings, and stretch out their heads, and cannot be happy until they hear their father.

“The squirrel, who lives in the hole where the two great branches part, hears what I say, and curls up his tail, while he turns his bright eyes towards the swinging nest which he can never reach.”

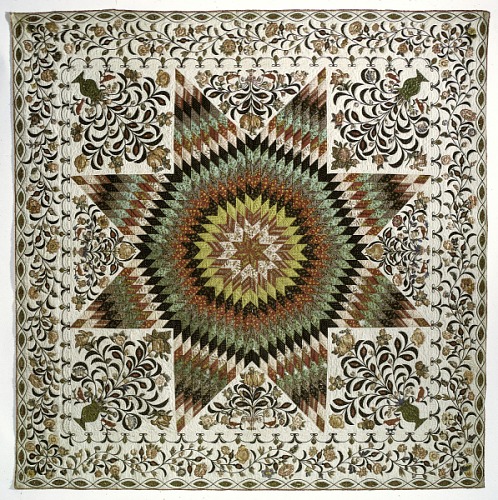

The fanning wind wafts across the road the voice of the old horse-chestnut, who also has a word to say about the bird’s-nests.

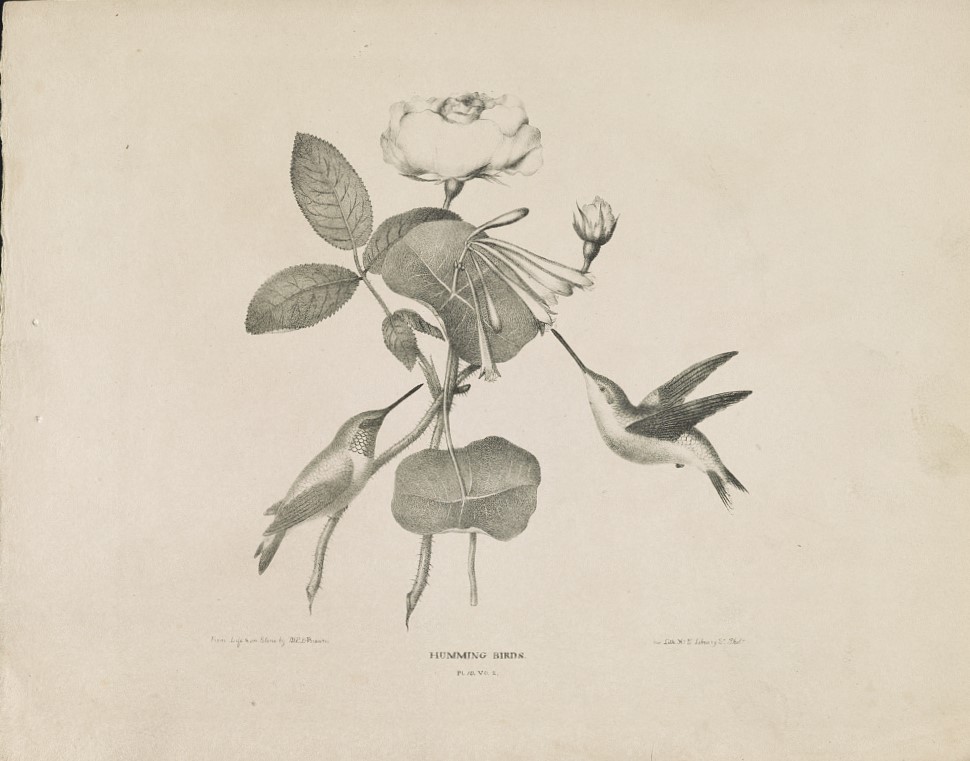

“When my blossoms were fresh white pyramids, came a swift flutter of wings about them one day, and a dazzlingly beautiful little bird thrust his long, delicate bill among the flowers; and while he held himself there in the air, without touching his tiny feet to twig or stem, but only by the swift fanning of long green-tinted wings, I offered him my best flowers for his breakfast, and bowed my great leaves as a welcome to him. The dear little thing had been here before, while yet the sticky brown buds which wrap up my leaves had not burst open to the warm sunshine. He and his mate, whose feather dress was not so fine as his, gathered the gum from the outside of the buds, and pulled the warm wool from the inside; and I could watch them, as they flew away to the maple yonder; for then the trees that stand between us had no leaves to hide the maple as they do now.

“Back and forth flew the birds, from the topmost maple-branch to my opening buds; and day by day I saw a little nest growing, very small and round, lined warmly with wool from my buds, and thatched all over the outside with bits of lichen, gray and green, to match what grew on the maple-branches about it; and this thatch was glued on with the gum from my brown buds. When it was finished, it was delicate enough for the cradle of a little princess; and the outside was so carefully matched to the tree by lichens that the sharpest eyes from below could not detect it. What a safe, snug home for the humming-birds!

“By the time the two tiny eggs were laid, I could no longer see the nest, for the thick foliage of other trees had built up a green wall between me and it. But for many days the mother-bird stayed away, and the father came alone to drink honey from my blossom cups; so I knew that the eggs were hatching under her warm folded wings; for I have seen such things before among my own branches in the robins’ nests and the bluebirds’.

“Now my flowers are all gone, and in their place the nuts are growing in their prickly balls. I have nothing to tempt the humming-bird, and he never visits me; only the yellow birds hop gayly from branch to branch, and the robins come sometimes.” And the horse-chestnut sighed, for he missed the humming-bird; and he flapped his great leaves in the very face of the linden-blossoms, and forgot to say, “Excuse me.” But the linden is now, and for many days, full of sweetness, and will not answer ungraciously even so careless a touch.

Yes, the linden is full of sweetness, and sends out the fragrance from his blossoms in through the chamber windows, and down upon the people who pass in the street below; and he tells, all the time, his story of how his pink-covered leaf-buds opened in the spring mornings, and unfolded the fresh green leaves, which were so tender and full of green juices that it was no wonder the mother-moth had thought the branches a good place whereon to lay her eggs; for, as soon as they should be all laid, she would die, and there would be no one to provide food for her babies when they should creep out.

So the nice mother-moth made a toilsome journey up my great trunk,” sung the linden, “and left her eggs where she knew the freshest green leaves, would be coming out by the time the young ones should leave the eggs.

“And they came out indeed, somewhat to my sorrow; for instead of being, like their mother, sober, well-behaved little moths, they were green canker-worms [1], and such hungry little things, that I really began to fear I should have not a whole leaf left upon me, when one day they spun for themselves fine silken ropes, and swung themselves down from leaf to leaf, and from branch to branch, and in a day or two were all gone.

“A little flaxen-haired girl sat on the broad doorstep at my feet, and caught the canker-worms in her white apron. She liked to see them hump up their backs and measure off the inches of her white checked apron with their little green bodies. And I, although I liked them well enough at first, was not sorry to lose them when they went. I heard the child’s mother telling her that they had come down to make for themselves beds in the earth, where they would sleep until the early spring, and wake to find themselves grown into moths just like their mothers who climbed up the tree to lay eggs. We shall see, when next spring comes, if that is so. Now since they went I have done my best to refresh my leaves and keep young and happy; and here are my sweet blossoms to prove that I have yet within me vigorous life.”

The elm-tree heard what the linden sung, and said, “Very true, very true: I too have suffered from the canker-worms; but I have yet leaves enough left for a beautiful shade, and the poor crawling things must surely eat something.” And the elm bowed gracefully to the linden, out of sympathy for him.

But the linden has heard the voices of the young robins who live in the nest among his highest boughs; and he must yet tell to the horse-chestnut how sad it was, the other day in the thunder-storm, when the wind upset the nest, and one little bird was thrown out and killed, while the father and mother flew about in the greatest distress, until Charley came, climbed the tree, and fitted the nest safely back into its place.

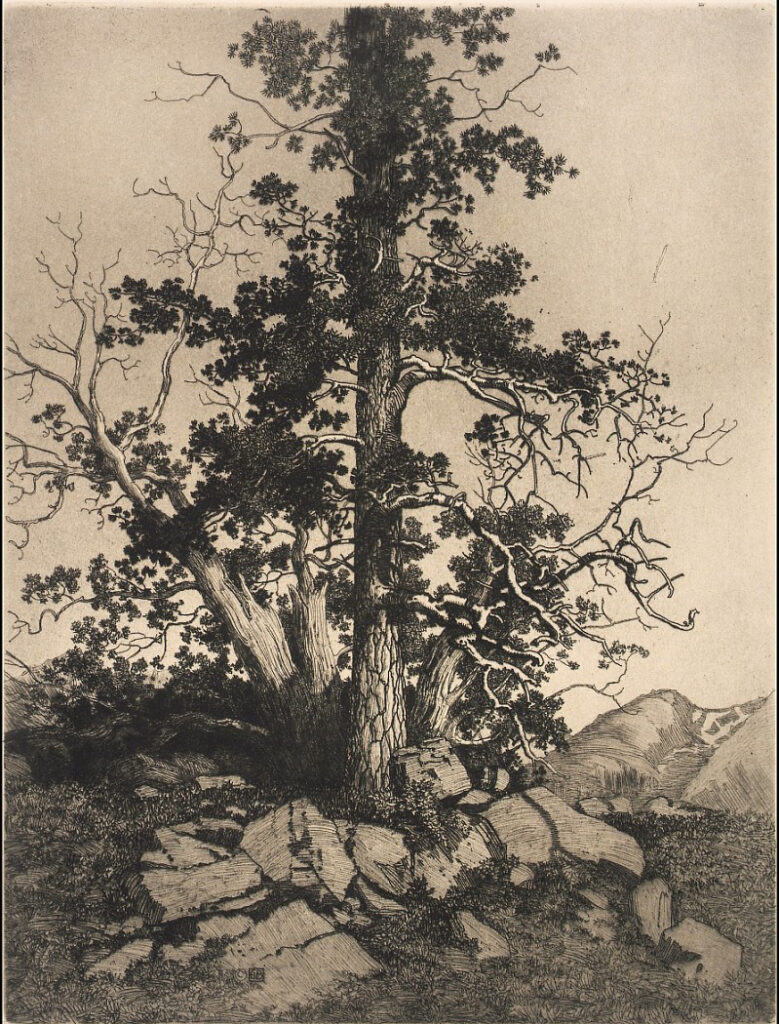

How much the trees have to say! And there is the pine, who was born and brought up in the woods: he is always whispering secrets of the great forest, and of the river beside which he grew. The other trees can’t always understand him; he is the poet among them, and a poet is always suspected of knowing a little more than any one else.

Sometime I may try to tell you something of what he says; but here ends the talk of the trees that stood in the village street.

Andrews, Jane. “The talk of the trees that stand in the village street.” Our Young Folks 4, no. 10 (October 1868): 598-600.

[1] Cankerworm larvae are commonly called inchworms. They start as eggs deposited on trees, transform into pupae in the soil, and emerge as moths. Significant cankerworm feeding over several years can cause trees to lose all their leaves, weakening and killing the branches.

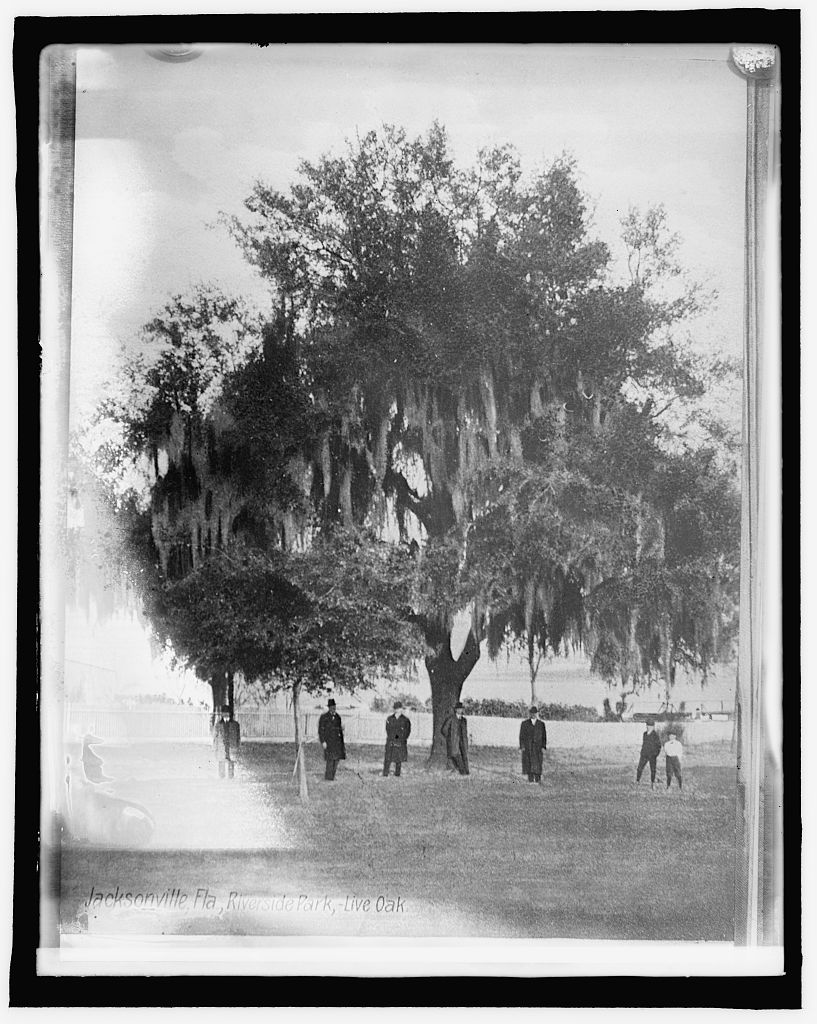

Contexts

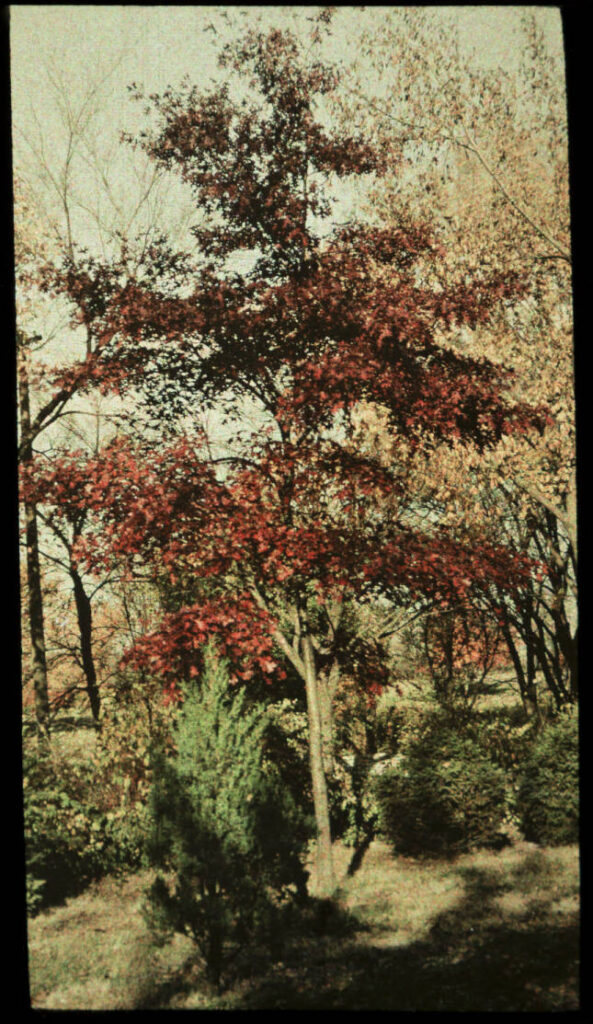

This article appeared on the cusp of a shift in where people lived in the U.S., as the late 19th century brought rapid growth of cities. While most people still lived in rural areas, the expansion of city life helped shape many aspects of modern life.

Resources for Further Study

- Urban Forests by Jill Jonnes considers a historical context for how trees have been integrated into U.S. cities.

- Arnoldia, the quarterly magazine of Harvard University’s Arnold Arboretum, contributes to an ongoing conversation about the importance of trees.

Contemporary Connections

Several modern organizations work to promote and support maintaining and increasing the presence of trees in cities:

- American Forests positions trees as a matter of environmental justice

- The UNECE Trees in Cities Challenge encourages mayors to make their cities greener

- The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations highlights the benefits of urban trees and offers several publications about the topic

Duke University ecologist Renata Kamakura shares their insights about helping trees survive in cities.