The Rat Hunt

By J. T. Trowbridge

Annotations by Will Smith

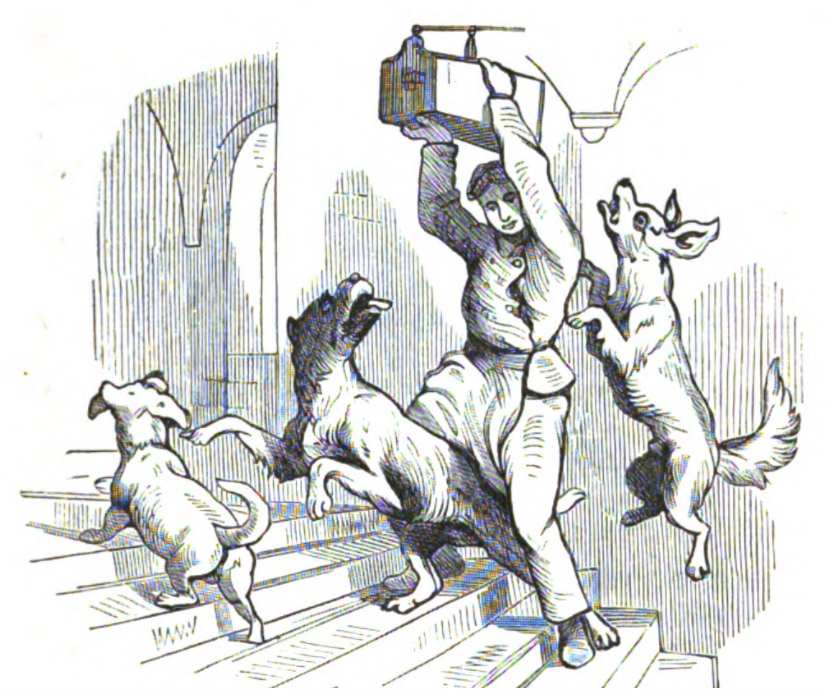

“COME, Towzer!” cries Rob: “here’s a rat in the trap! Come, bushy-tailed Bouncer! come, short-legged Snap! The cunning young rogue! we have caught him at last. Hurrah, my brave hunters! — but don’t be too fast; Down, Towzer! off, Bouncer! you can’t have him yet. Be civil, old fellow! be patient, my pet! Out here in the yard, where there’s plenty of space, And nothing to hinder, we'll give him a chase.

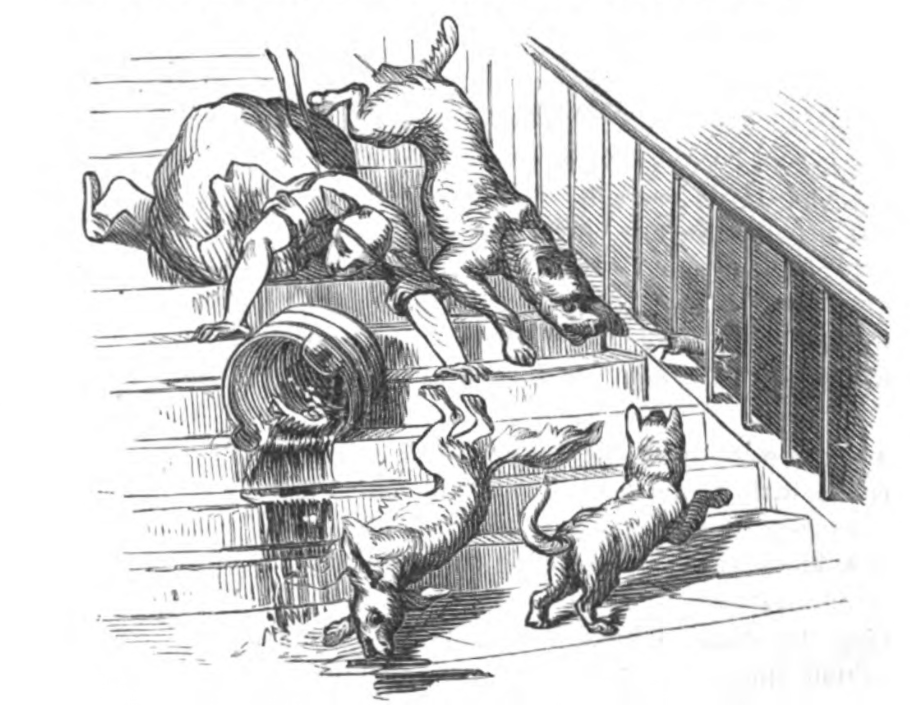

“Now, Towzer! now, Bouncer! look out for the fun. There! steady! be ready! I’m letting him run; Be sharp, now — eyes open, — staboy! There he goes! Quick, Bouncer! he’s scudding right under your nose! “Along by the carriage-way — up by the spout — Now take him, now shake him, before he gets out! I’m ashamed of your hunting; you’re clumsy as bears! There he is again! after him — up the hall stairs! “You shouldn’t be scrubbing right here in the way, O Bridget! — I told you so! you’ve got your pay, With your old tub of water!” And down through the hall Tumble tub, Bridget, Bouncer, spilled water, and all.

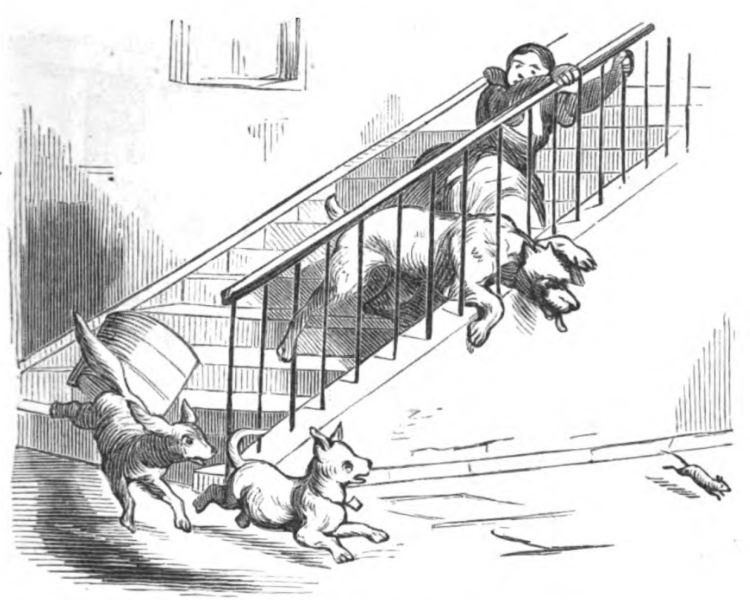

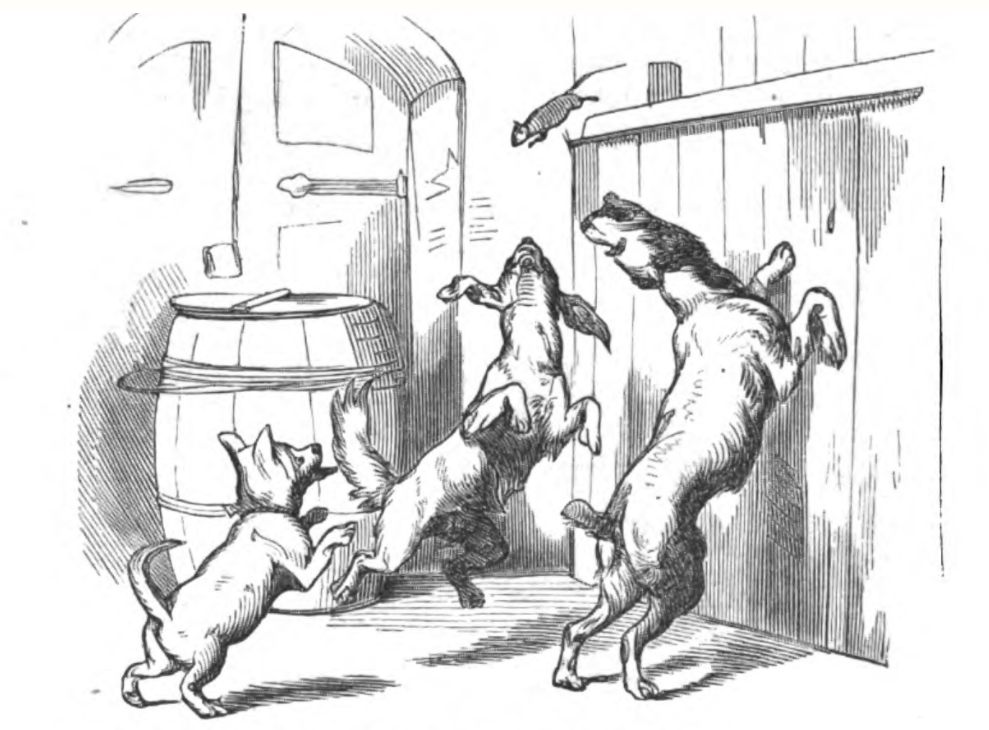

“Now, Towzer, you have him! No — yes!” From the stair He leaps through the rods of the banister, where Old Towzer gets caught at the instant his teeth Are ready to snap his poor victim beneath. A rally, a dash, and across the hall floor They pursue to the store-room, rush in through the door, And follow, with furious yelping and leaping, Close under the cleat along which he is creeping. Beyond stands a cask, — he springs off upon that; The dogs are there almost as soon as the rat, Capsizing the cover with clatter and din; — Away goes the rat, while a dog tumbles in.

Who cares all the while for the rat and his troubles? For life, ’t is for life that he dodges and doubles, — For even a rat finds it pleasant to live, — And ’t is death to be caught; and O, what would he give — What mountains of cheese and what treasures of corn — To be back in the dark cellar where he was born! In vain by the churn and the firkin, in vain Behind barrels he lurks, a brief respite to gain. They are dragged from the wall, and, with clamor and scrabble, Behind and before comes the mad, rushing rabble, Upsetting the churn, overturning the firkin, Not leaving him even a corner to lurk in.

Out into the passage away they go dashing, Through entry and pantry, with dashing and crashing. Snap, always too late by a second appears Excitedly barking and pricking his ears; While along with them speeds the young rat-catcher, clearing The way for them, stamping and shouting and cheering. I wonder how one little frightened rat feels With a boy and three wild, yelping curs at his heels! “Seek! seek now!" The poor, panting fugitive has a Last chance for himself on the old back piazza. Now Towzer is on him — he jumps from his jaws; Nouncer and Snap — he darts under their paws; Now all three together! — in one second more Three moist muzzles meet at a hold in the floor,

Just in season to tickle their tongues with the slight Taper-end of a tail as it frisks out of sight! They valiantly bark at the hole, and then, falling Exhausted beside it, lie gasping and lolling. Rob voes he will swap his three dogs for one cat, — But it wasn't so bad, after all, for the rat!

TROWBRIDGE, J. T. “The Rat Hunt.” OUR YOUNG FOLKS: AN ILLUSTRATED MAGAZINE FOR BOYS AND GIRLS 9, No. 11 (November 1873): 661-65.

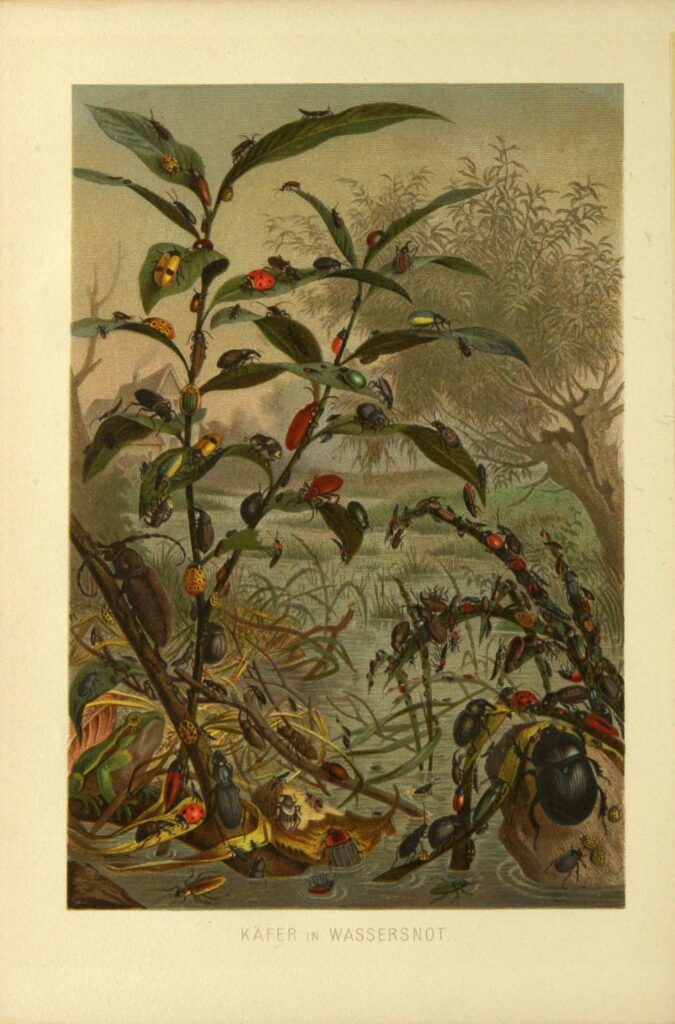

Contexts

“The Rat Hunt” is an original poem by J.T. Trowbridge, one of the editors, along with Lucy Larcom, of Our Young Folk. The printing similarly includes an uncommon number of illustrations, possibly indicating a degree of editorial privilege. This poem provides an interesting presentation of space through the hunt’s movement through the house, subtly providing a social context for a family that might own dogs as pets and finds entertainment with this type of sport — one that would also have paid labor to clean their home. The empathy shown to the rat is unlike in some other poems, such as “Turkey. An Ode to Thanksgiving.” Here, Trowbridge offers an attempt at understanding events from the animal’s perspective; this poem does not end with a justification of the dogs’ attacks on the rat.

Definitions from Oxford English Dictionary

churn: A vessel or machine for making butter, in which cream or milk is shaken, beaten, and broken, so as to separate the oily globules which form the butter from the serous parts.

firkin: A small cask for liquids, fish, butter, etc., originally containing a quarter of a ‘barrel’ or half a ‘kilderkin’.

Resources for Further Study

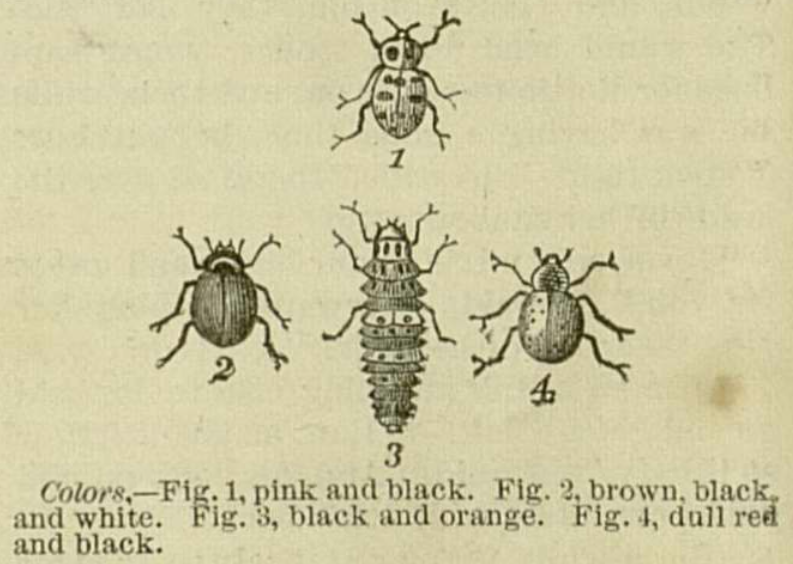

- An overview of the dog breeds that were specifically bred for the activities depicted in the poem

- An overview of dog breeds and the jobs they were bred to do

- An article focusing on the often misunderstood rat

Contemporary Connections

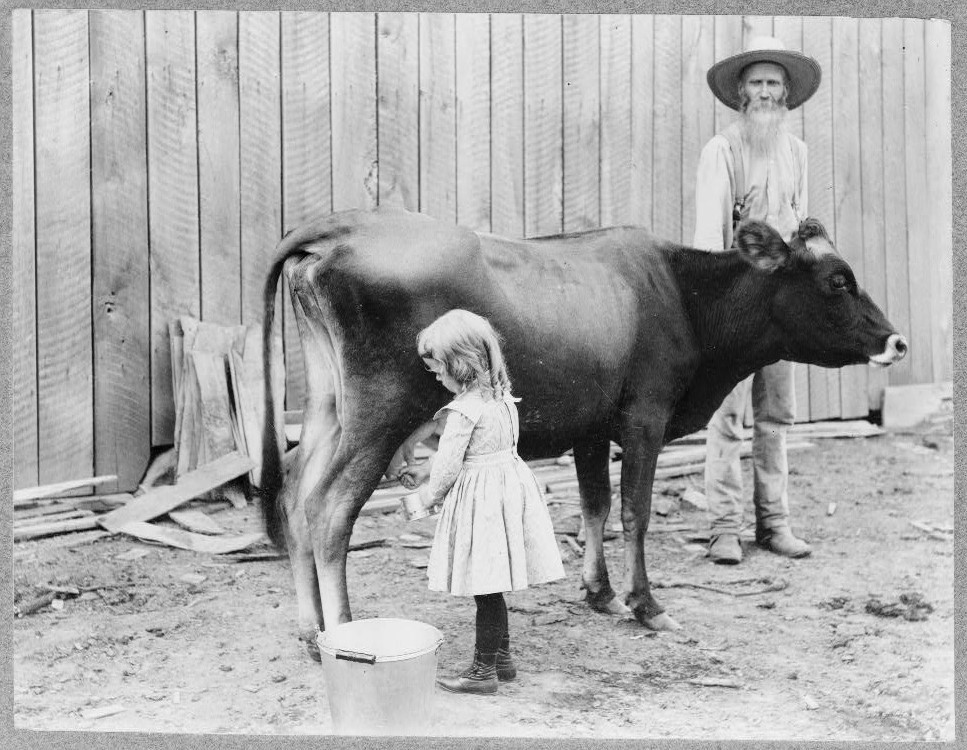

If your dog is a home pet and companion, it can be difficult to imagine them carrying out duties such as ratting or herding. Not very long ago, jobs like those were a dog’s primary function. While modern dogs are much less likely to do the tasks for which they were initially bred, many breeds have retained the instincts that allowed them to do their jobs — and the energy that went along with those instincts. This poem reminds us that dogs are energetic creatures with a desire to follow their instincts, which should be considered when choosing a dog to bring into your family. Additionally, this poem demonstrates that allowing your dog to chase other animals is not an enjoyable activity for the animal being chased. Thankfully, dog toys of every shape and size replace creatures like the rat in this poem.