A Lullaby

By Cora J. Ball Moten

Annotations by Rene Marzuk

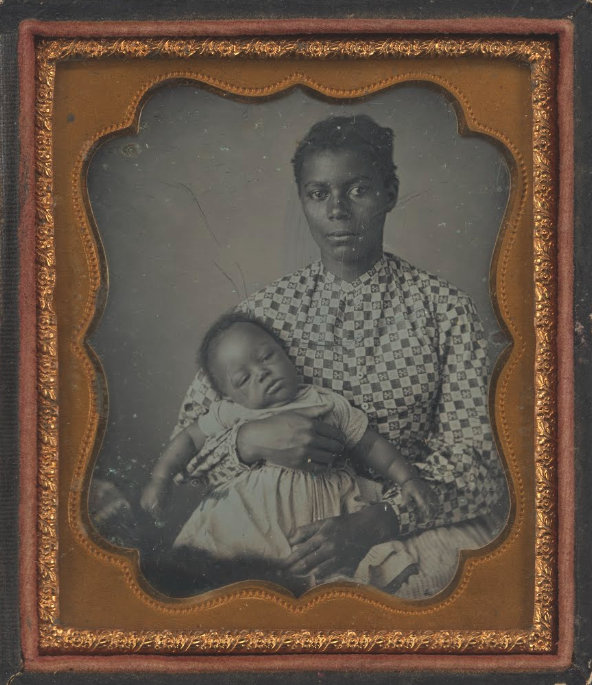

Dusky lashes droop and fall, Night-winds whisper, night-birds call. Closed your tired sleepy eyes, Earth is singing lullabies. Kindly twilight shadows creep O’er a world that longs for sleep. Little dusky babe of mine Close those sleepy eyes of thine. Mother’s love will softly keep Watch above you while you sleep. Cruel hate and deadly wrong Cannot silence mother’s song Though against thy soft brown cheek She may hide her face and weep. Sleep, brown baby, while you may Peacefully, at close of day. Oh, that mother’s love could guard, Keep thee safe ‘neath watch and ward From the cruel deadly things That await thee while she sings. Prejudice and cold white hate: These, my baby, these, thy fate, Little, gentle, trustful thing, Thus, these sobs, the while I sing.

MOTEN, CORA J. BALL. “A LULLABY.” THE CRISIS, VOL. 8, NO. 6 (OCTOBER 1914): 296.

Contexts

Starting in 1912, the October issues of The Crisis, the official magazine of the NAACP, were dedicated to children. A typical edition of these children’s numbers would contain a special editorial piece and two or three literary works specifically for children, while still including the serious pieces about contemporary issues with a focus on race that The Crisis was known for. These October numbers were sprinkled with children’s photographs sent in by the readers.

In his first editorial for the Children’s number in 1912, W. E. B. Du Bois wrote that “there is a sense in which all numbers and all words of a magazine of ideas myst point to the child—to that vast immortality and wide sweep and infinite possibility which the child represents.”

The success of The Crisis’ children’s number led to the standalone The Brownies’ Book, a monthly magazine for African American children that circulated from January 1920 to December 1921 under the editorship of Du Bois, Augustus Granville Dill, and Jessie Fauset.

Definitions from Oxford English Dictionary:

watch and ward: The performance of the duty of a watchman or sentinel, esp. as a feudal obligation. Now only (as often in earlier times) a rhetorical and more emphatic synonym of watch.

Resources for Further Study

- In her 2006 book Children’s Literature of the Harlem Renaissance, Katharine Capshaw Smith refers to Cora J. Ball Moten’s poem “A Lullaby” within the context of The Crisis Magazine as representative of “maternal sorrow songs,” in which mothers “sing lullabies tinged with despair over the cribs of sleeping, still innocent, babes” (Smith 18). Smith connects this genre to the NAACP’s antilynching efforts.

- In her 2011 book Racial Innocence: Performing American Childhood from Slavery to Civil Rights, Robin Bernstein illustrates how the American idea of childhood innocence became racialized and excluded black children starting in the mid nineteenth century. A poem like Cora J. Ball Moten’s “A Lullaby,” enacts a powerful corrective to this ideological trend while also bringing attention to the anxieties of black motherhood.

- In 1943, Cora J. Ball Moten wrote “Negro Mother to Her Soldier Son,” a poem in which the speaker addresses her son lost in a war, perhaps World War II. Against the background of “A Lullaby,” the beginning of “Negro Mother to Her Soldier Son” is particularly poignant:

“Your tiny fingers kneaded my dark breast

like wind-stirred petals on the jungle bloom

of my fierce love for you, flesh of my flesh.

My knotted hands, work-calloused thru the years,

Once smoothed the fleecy softness of your hair.

That touch, remembered, thrills my fingers still.”

The poem appears in its entirety on volume 21 of Opportunity: Journal of Negro Life (1943), available through Google Books.