Legend of Horn Lake

By Stella Le Flore Carter (Cherokee-Chickasaw), age 9

Annotations by Karen L. Kilcup

My Aunt Lizzie lives at the head of the beautiful Washita canyon. [1] She is almost a full-blood Chickasaw, and has all the ways of a full-blood Indian. She tells many beautiful stories about her people, as she calls the Chickasaws. [2] She calls these tales legends and traditions, but Papa says they are pipe stories. Among others she told me what she calls the legend of Horn Lake, which I will tell you as she told it to me. [3]

Many years ago, when your Great Grandfather wore the breech clout and hunting shirt, a clan of my people lived in a beautiful valley, near the line of Mississippi and Tennessee.

The Chief of this clan had a beautiful daughter, named Climbing Panther. [4] She was known among all the Chickasaws for her pretty face and perfect form. One day the young men of the tribe cut down a large bee tree for they wanted the honey. [5] The trunk of the tree was found to be hollow and full of water, and a fish was seen coming to the surface for air. Climbing Panther wanted to get the fish, but the old Medicine Man fussed at her, and told her not to do it. But she took the fish home to her father’s wigwam[,] cooked it and ate it. She became very thirsty and they brought her water, but she could not get enough. At last she went to the spring and drank the water as fast as it ran from the spring. Before leaving camp she told her father that she was sick, and to call his people together and have a big Pashofa, or Medicine Dance. [6]

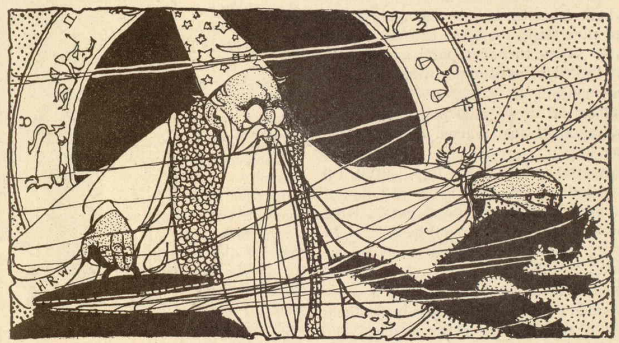

Her father called the people together that night, and when they were forming lines for the Tikbahoka, [7] the men on one side and the women on the other, they heard an awful roaring noise. A big snake as big as a horse appeared between the two lines. It had long horns and on its head was the face of Climbing Panther. Then they all knew that Climbing Panther had turned to a snake.

The lightning flashed and the Heavens gave a mighty roar. The body of the snake burst open, the ground sank and everything was covered with water except the long horns of the snake. This is the way Horn Lake was made. And the great horns of the snake can be seen sticking above the water today. And it was all caused by Climbing Panther’s disobedience.

STELLA LE FLORE CARTER, “LEGEND OF HORN LAKE,” TWIN TERRITORIES 5, NO. 5 (MAY 1903): 182-83.

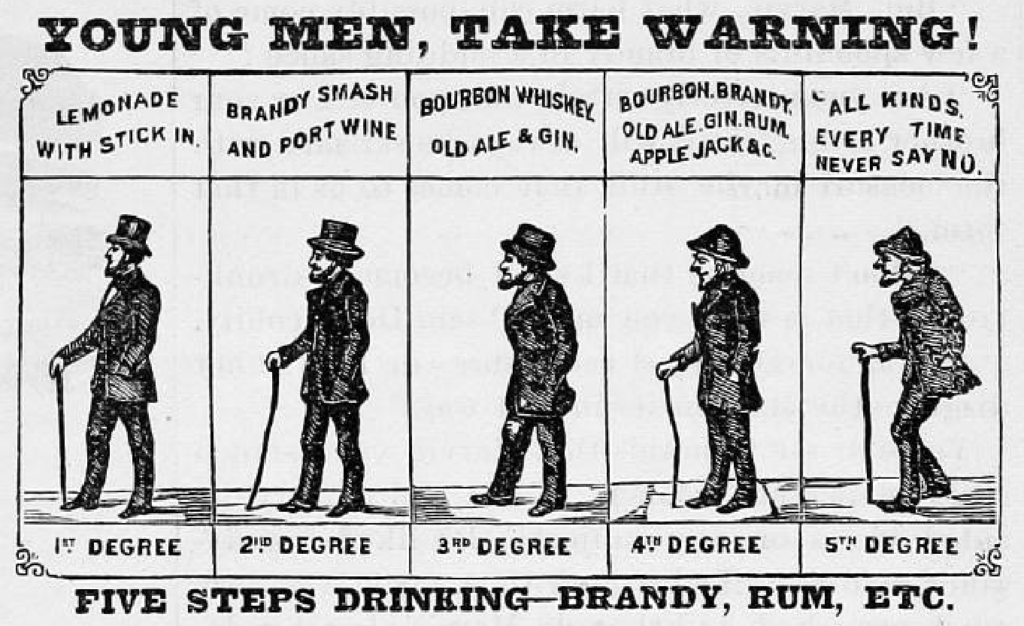

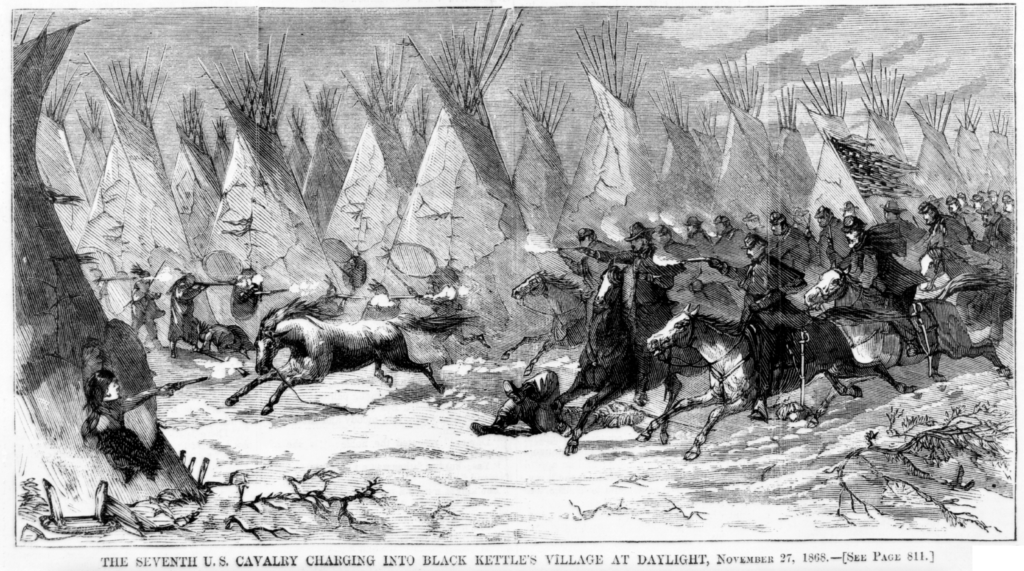

Harper’s Weekly 12 (December 1868): 804. Public domain.

[1] The Washita River, which meanders across many miles in southwest Oklahoma, figures tragically in Native American history. See Contexts and Resources for Further Study, below.

[2] The Chickasaw people were among the groups called the “Five Civilized Tribes” that the U.S. Government removed to Indian Territory (now part of Oklahoma) on the Trail of Tears. See Resources for Further Study, below.

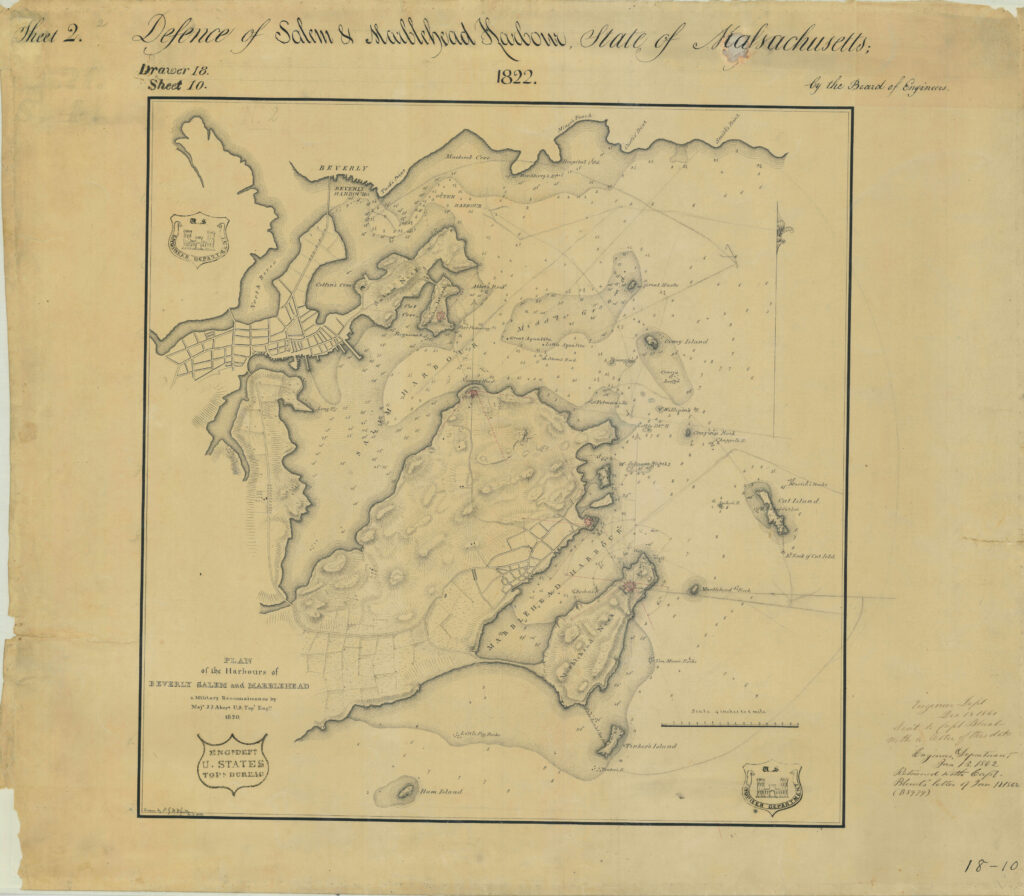

[3] Horn Lake does not appear in any contemporary or historical maps of Oklahoma. The location the story references is almost certainly in the traditional homeland of the Chickasaws. Crossing the Tennessee-Mississippi border, Horn Lake appears on a 1932 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers topographic map, as well as on contemporary Google maps. Thanks to Jessica Cory for locating this information.

[4] The name Climbing Panther may suggest that the chief’s daughter belonged to the Panther Clan, traditionally regarded as hunters.

[5] As its name suggests, a bee tree contains a colony of honeybees. Those we regularly reference today are not native to North America but were brought here from Europe in the seventeenth century. Before this time, American Indians “enjoyed a different kind of honey prior to the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors. The Mayans and Aztecs ate honey from a bee, Melipona beecheii, that used hollowed-out logs as hives.” See Carson in Resources for Further Study, below.

[6] “Pashofa” is a traditional Chickasaw dish composed of pashofa corn and pork. The Chickasaw Nation website, which contains recipes, comments that it “was, and still is, served at large gatherings of Chickasaws, for celebrations and ceremonies.”

[7] The author may have transcribed this word imprecisely, for a search reveals no results. The context suggests that it references the Medicine Dance mentioned in the previous paragraph.

Contexts

Stella Carter’s story exemplifies a notable genre of Native American literature, the traditional tale that explains the origin of a natural feature. The story’s key emphasis, however, lies in what the narrator calls “Climbing Panther’s disobedience”: in rejecting her elders’ wisdom and prioritizing her individual desires, she endangers the entire tribe.

Carter’s narrative does not mention the 1868 Washita Massacre, but her aunt would almost certainly have known about this attack in which U.S. soldiers led by Lt. Colonel George Armstrong Custer decimated the village of Peace Chief Black Kettle and killed the chief. Four years earlier, the horrific Sand Creek Massacre by U.S. soldiers in Colorado had killed many women and children, but Black Kettle attempted to maintain peaceful relations with the federal government. The websites of the National Park Service (NPS) and the Washita Battlefield National Historic Site in Oklahoma provide some historical background, although readers should be wary of non-Native accounts. The NPS description acknowledges that “Black Kettle, a respected Cheyenne leader, had sought peace and protection from the US Army and had signed the Little Arkansas Treaty in 1865 and the Medicine Lodge Treaty in 1867.” For eyewitness Cheyenne accounts, see Hardoff, below.

Resources for Further Study

- Brown, Dee. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West. 1970; rpt. New York: Henry Holt, 2007. See 167-68, 243.

- Carson, Dale. “The Origins of Golden Honey and its Gastronomic and Medical Uses.” Indian Country Today, January 26, 2013.

- “Carter, Charles David, 1868-1929.” Biographical Dictionary of the United States Congress.

- Hardoff, Richard G., ed. Washita Memories: Eyewitness Views of Custer’s Attack on Black Kettle’s Village. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2006. Notable because it contains accounts by Cheyenne Indians who witnessed the massacre.

- Hatch, Thom. Black Kettle: The Cheyenne Chief Who Sought Peace But Found War. Hoboken: John Wiley, 2004. See Chapters 8, 9, and 12.

- “History.” Office of the Governor. The Chickasaw Nation. This site encompasses Chickasaw history from the pre-settler period to the present.

- Horwitz, Tony. “The Horrific Sand Creek Massacre Will Be Forgotten No More.” Smithsonian, December 2014.

- Kosmerick, Todd J. “Carter, Charles David (1868-1929).” Oklahoma Historical Society.

Pedagogy

Boatman, Christine. “Lessons Learned in Teaching Native American History.” Edutopia. George Lucas Educational Foundation, September 18, 2019. “A white teacher shares resources and things she’s learned: Be humble, find the gaps in your knowledge, and listen to Native voices.”

“Chickasaw Nation Curriculum.” The essential guide for teaching primary and secondary grades about the Chickasaw Nation.

“English Language Arts: Oral Traditions.” Oregon Department of Education.

“Maps and Spatial Data: Map Resources for Teaching Oklahoma History.” Edmon Low Library. Oklahoma State University. Includes maps of Indian Territory from 1889 and of the proposed State of Sequoyah from 1905.

Reese, Debbie (Nambe Pueblo). “American Indians in Children’s Literature.” Website with numerous pedagogical resources.

———. “Proceed with Caution: Using Native American Folktales in the Classroom.” Language Arts 84, no. 3 (January 2007): 245-56. Open-access article that contains additional valuable resources for teachers at various levels.

“Teacher’s Guide. American Indian History and Heritage.” EDSITEment! National Endowment for the Humanities. “Transforming teaching and learning about Native Americans.” Native Knowledge 360° Education Initiative. National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian. The site offers educators and others free webinars, including many hosted by Native Americans, aimed to correct problematic narratives about Native Americans; it maintains an archive of previous sessions.

Contemporary Connections

For a Native American perspective on the events of November 1868, see Winter Rabbit (Métis). “Washita Massacre of November 27, 1868: 151st Anniversary.” Daily Kos, November 27, 2019.

Northwest of Foss Reservoir (and of the town of Washita) lies the 8,075-acre Washita National Wildlife Refuge, established in 1961. The refuge encompasses both resources for geese and other wildfowl and seven active natural gas wells. The Washita Battlefield National Historic Site lies near Cheyenne, Oklahoma.