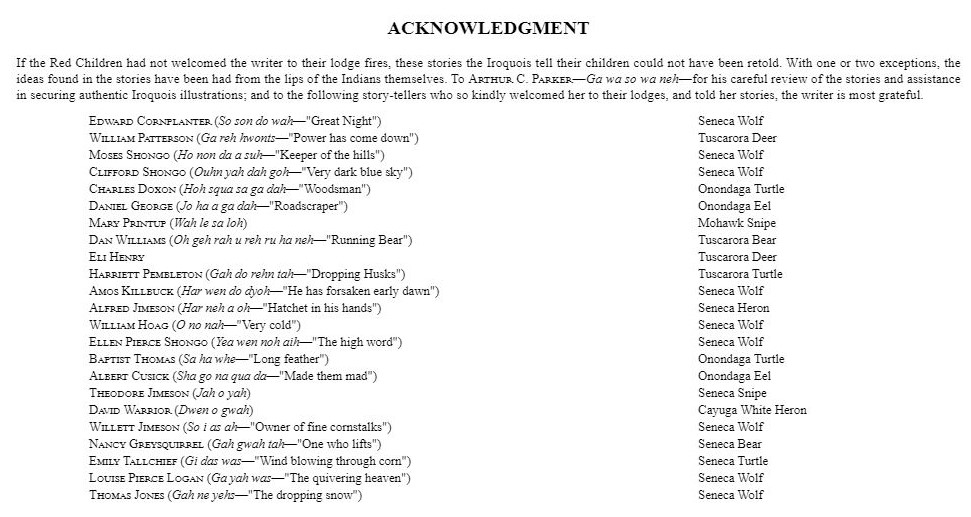

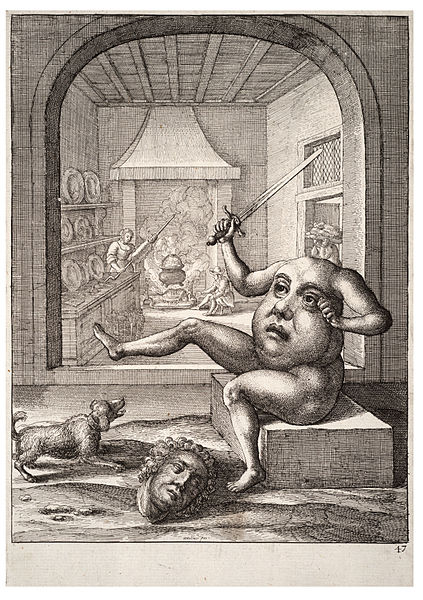

The Misfortunes of a Yellow Bird

By “C.”

Annotations by Celia Hawley

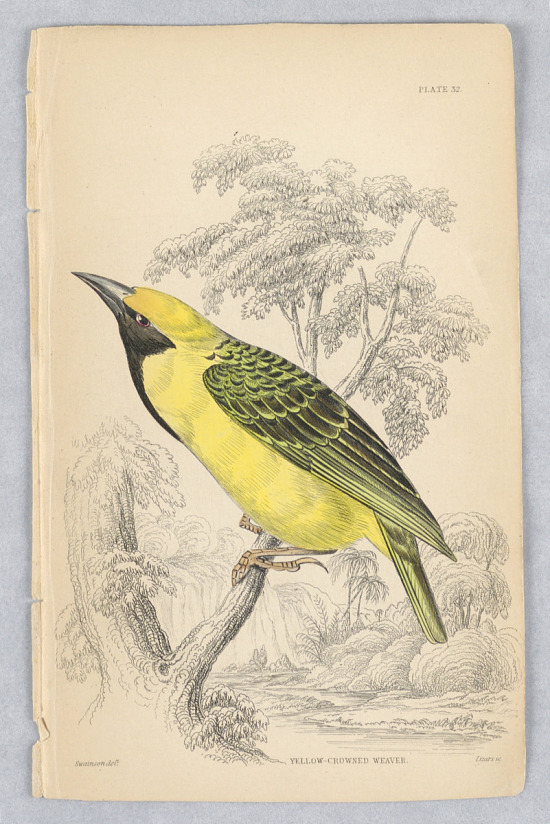

Print from William Swainson engraving, brush and watercolor on paper, 1837. Cooper

Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, N.Y.

When I gained the first knowledge I had of my own existence, I found myself resting very comfortably in the hollow of a neat little house, built of divers[1] materials, such as straw, thread, mud, &c., all being very ingeniously worked together, giving the nest the two needful qualities of strength and warmth. To the truth of the former quality I can give full testimony; having employed myself during my long confinement after birth, in the vain attempt of pulling to pieces my rustic abode.

I had several brothers and sisters for my companions. For many days we lay very quietly, and moved only to receive the food which our kind parents brought us. The foliage of the tree in which our nest was built was very thick, and afforded a delightful shelter from the sun, and reflected mild and pleasant light upon our just opening eyes. After a few days our bodies became strangely metamorphosed, and we appeared like new creatures, in our dress of yellow, ornamented with black edgings. I was much surprised at the sudden change, yet pleased; for truly we were rather uncouth looking animals at our first appearance. So happy were we now, with our splendid garb, that we began to chirp and made many awkward attempts to get out of our nest; we at last succeeded in our efforts to gain the edge of it, and felt quite proud at our wonderful achievement; and our parents sung merrily over us. In a few days, these fond parents taught us to spread our wings and fly to the nearest branches of the tree in which we lived; and soon we were able to fly to all the neighboring trees.

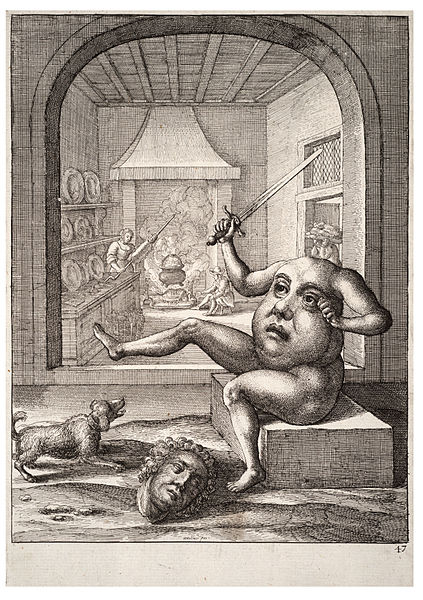

after John James Audubon, 1860. Smithsonian American Art Museum

and its Renwick Gallery, Washington, D.C.

We were perfectly happy; our days were spent in singing, and flying, and feasting ourselves from the newly budded trees around us, and our nights in quiet and undisturbed repose. We dreamed not of the evil that was awaiting us; but it came; and those happy days which I once knew, will I fear never return.

One beautiful morning we had all been amusing ourselves, by hopping from branch to branch, and flying from tree to tree, until we were quite tired, – and had returned to our nests. We had just quietly laid ourselves to rest, and our parents had gone in search of food, when we heard a loud noise beneath the tree, and immediately the bough, on which our home was built, began to shake so violently, that we were every moment in danger of being thrown down. We were all much terrified, but remained in our nest. In that we had ever found a refuge from the storm, from the birds who were our enemies, and from every other danger which had before threatened us. We therefor clung to it now as our only hope. Presently something was thrown over our nest, which left us in perfect darkness; we were almost dead with fright, and our nest was torn rudely from the tree. Then, for the first time, we heard the sound of the human voice; it sounded harsh and stunning to our ears, and only increased our fear. We were carried some distance with great care. We were then uncovered, but where we were I knew not; fright prevented my knowing.

The first thing I was conscious of, was being separated from my dear brothers and sister, and being placed in a very odd thing, which the people round me called a cage. I looked about as soon as I was placed in this, and found myself surrounded by numerous boys, some talking loudly, others screaming until I nearly fainted with fear. My prison house looked so slight and frail, that I imagined by beating it, I might force my way out. So I commenced flying against the sides, until seeing it had no effect, I sunk down exhausted by fright and exertion. Many of the boys thought I was dying, and begged my release; but the cruel boy who stole me from my happy home, would not grant their request.

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.

For weeks I was kept a prisoner; they treated my kindly — but it was slavery. Oh! how I sighed for my own dear home, for my native woods, with their beautiful shades and the dear music of my woodland loves! Oh, freedom is sweet to the bird, as well as to man! The boys seemed to love me; I could have loved them, had they given me liberty.

Since my captivity there are many kind faces that look at me, as though they wish to set me free; there is one who has often begged for my release, but my hard-hearted master will not grant it. He says he wishes to keep me; and for what wicked purpose think you? What, but, as he says, to lure other birds into his snares! So I have had in my cage a trap fixed, well baited: and it has been my duty to sing, and thus call the birds in to the trap.

One day a cat passed my cage, and the friendly creature, beast though she is, would have opened for me a passage out of my prison, had not the boys, seeing her designs, driven her away. When my imprisonment will end I know not. I live only in the hope that my master’s heart will be softened by my unhappy situation, and that he will set me free. Had I a human voice I would tell him how cruel he is thus to imprison me, and to make my confinement the means of reducing others into the same slavery. And if he would not hear my complaint, I would then appeal to his master, and try to touch his heart with my story, and beg of him to reprove my hard hearted keeper and open the door of my prison, and then might I hope to return to my beautiful home in the tree!

Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, N.Y.

C. “THE MISFORTUNES OF A YELLOW BIRD.” The Juvenile Miscellany 6, no. 3 (JulY 1834): 299.

Contexts

Excerpt from History.com’s U.S. Slavery: Timeline, Figures & Abolition:

“By the 1830’s there were more and more voices joining the anti-slavery cause. In the North, the increased repression of southern Black people only fanned the flames of the growing abolitionist movement. From the 1830s to the 1860s, the movement to abolish slavery in America gained strength, led by free Black people such as Frederick Douglass and white supporters such as William Lloyd Garrison, founder of the radical newspaper The Liberator, and Harriet Beecher Stowe, who published the bestselling anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin.”

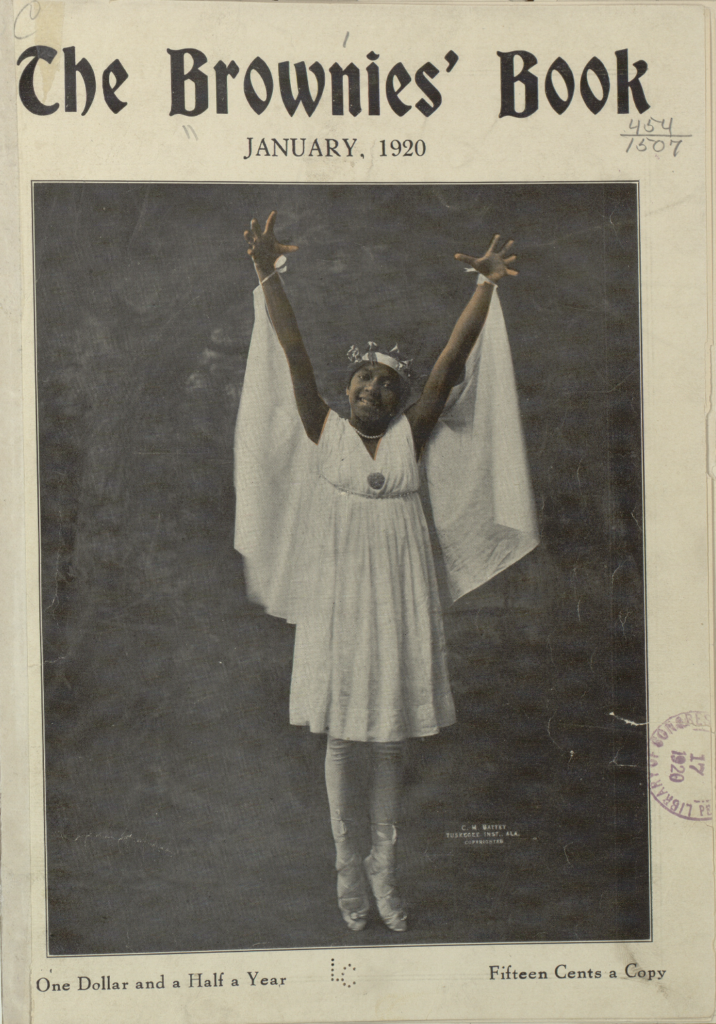

Children’s magazines such as The Juvenile Miscellany were vehicles for much of the abolitionist sentiment of the time.

Resources for Further Study

- The child’s anti-slavery book: containing a few words about American slave children and stories of slave-life by Julia Colman and Matilde G. Thompson has this passage: “Children, you are free and happy. …Thank God! thank God! my children for this precious gift. … But are all children in America free like you? No, no! I am sorry to tell you that hundreds of thousands of American children are slaves. Though born beneath the same sun and on the same soil as yourselves, they are nevertheless SLAVES. Alas for them! … I want you to remember one great truth regarding slavery, namely, that a slave is a human being, held and used as property by another human being, and that it is always A SIN AGAINST God to thus hold and use a human being as property!”

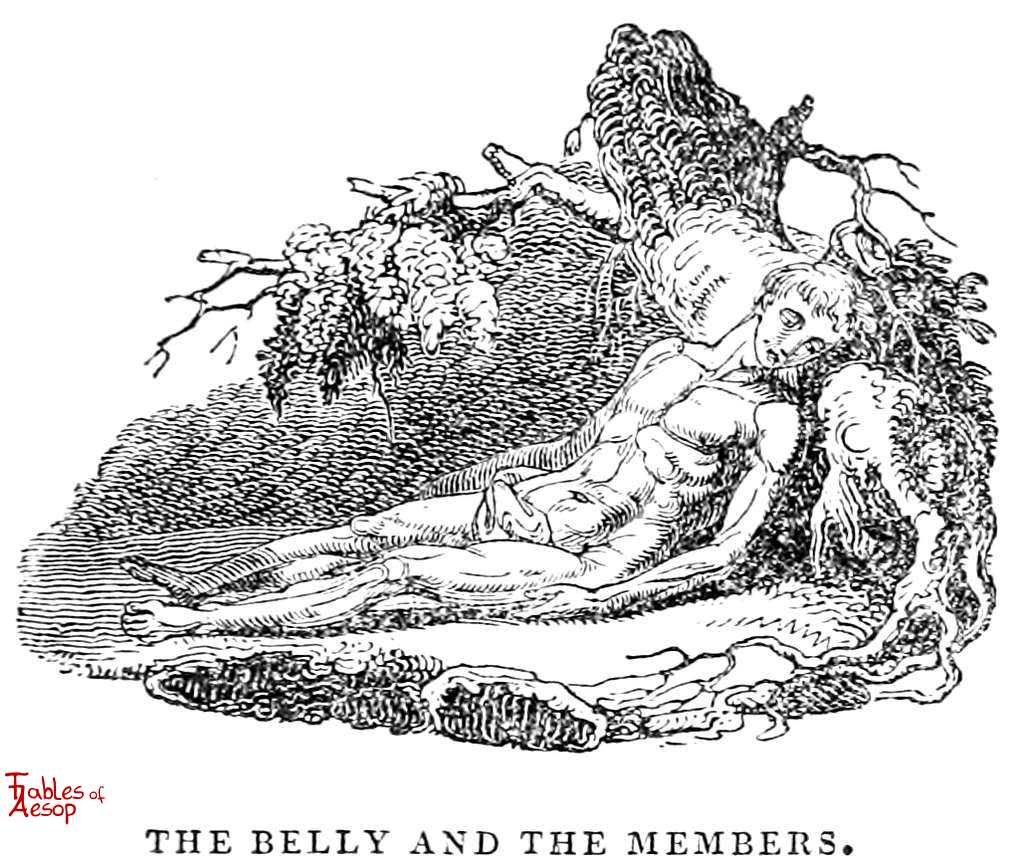

- Aesop’s Fables: Timeless Stories with a Moral

- Flocabulary: Video and vocabulary games for the fables of Aesop

Contemporary Connections

We can make a connection between the anonymous 19th-century writer of this piece and a well-known 20th-century one. Maya Angelou chose the same allegorical image, that of a caged bird, for the title of her critically acclaimed 1969 autobiography, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. Angelou was an American poet and author who was the recipient of many honors, among them the 2010 Presidential Medal of Freedom.

[1] diverse