How the Indian Corn Grows

By Jane Andrews

Annotations by josh benjamin

THE children came in from the field with their hands full of the soft, pale-green corn-silk. Annie had rolled hers into a bird’s-nest, while Willie had dressed his little sister’s hair with the long, damp tresses, until she seemed more like a mermaid, with pale blue eyes shining out between the locks of her sea-green hair, than like our own Alice.

They brought their treasures to the mother, who sat on the door-step of the farm-house, under the tall, old elm-tree that had been growing there ever since her mother was a child. She praised the beauty of the bird’s-nest, and kissed the little mermaiden to find if her lips tasted of salt water; but then she said, “Don’t break any more of the silk, dear children, else we shall have no ears of corn in the field, — none to roast before our picnic fires, and none to dry and pop at Christmas time next winter.”

Now the children wondered at what their mother said, and begged that she would tell them how the silk could make the round, full kernels of corn. And this is the story that the mother told, while they all sat on the door-step under the old elm.

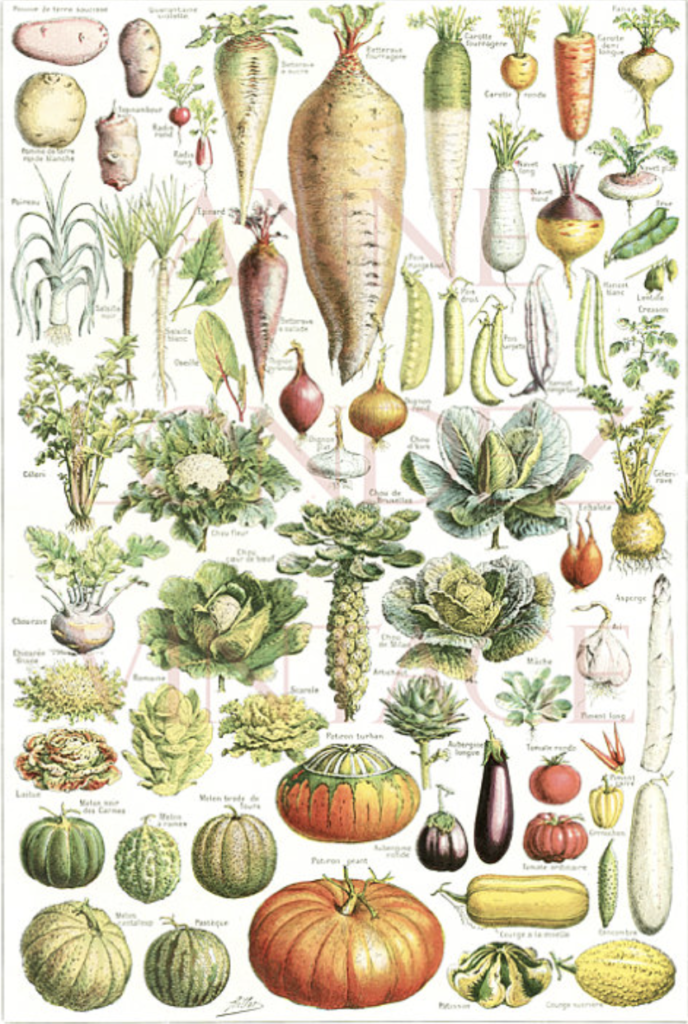

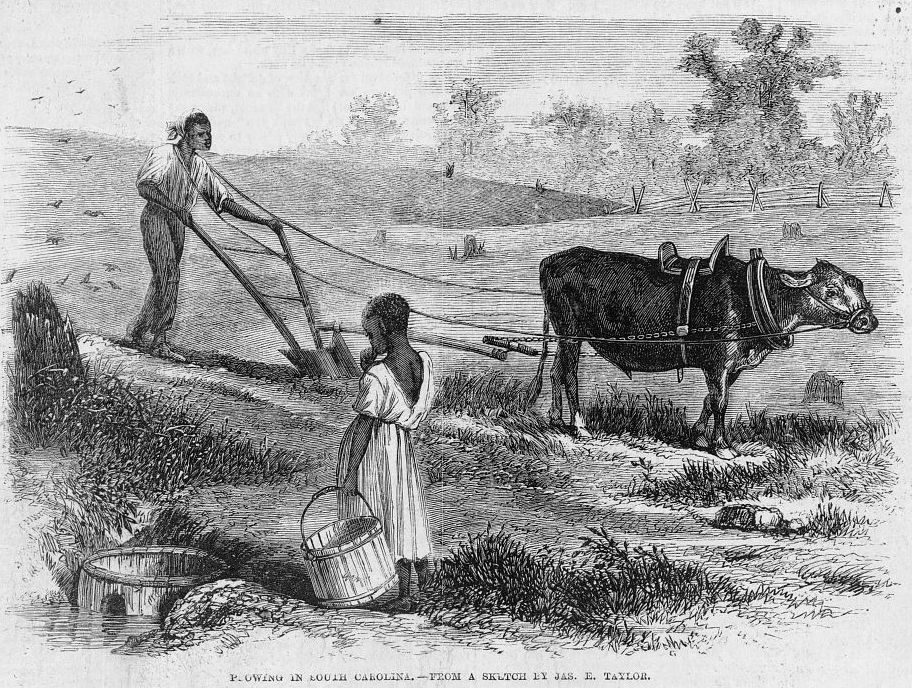

“When your father broke up the ground with his plough, and scattered in the seed-corn, the crows were watching from the old apple-tree; and they came down to pick up the corn; and indeed they did carry away a good deal ; but the days went by, the spring showers moistened the earth, and the sun shone, and so the seed-corn swelled, and, bursting open, thrust out two little hands, one reaching down to hold itself firmly in the earth, and one reaching up to the light and air. The first was never very beautiful, but certainly quite useful; for, besides holding the corn firmly in its place, it drew up water and food for the whole plant; but the second spread out two long, slender green leaves, that waved with every breath of air, and seemed to rejoice in every ray of sunshine. Day by day it grew taller and taller, and by and by put out new streamers broader and stronger, until it stood higher than Willie’s head; then, at the top, came a new kind of bud, quite different from those that folded the green streamers, and when that opened, it showed a nodding flower which swayed and bowed at the top of the stalk like the crown of the whole plant. And yet this was not the best that the corn plant could do, — for lower down, and partly hidden by the leaves, it had hung out a silken tassel of pale, sea-green color, like the hair of a little mermaid. Now, every silken thread was in truth a tiny tube, so fine that our eyes cannot see the bore of it. The nodding flower that grew so gayly up above there was day by day ripening a golden dust called pollen, and every grain of this pollen — and they were very small grains indeed — knew perfectly well that the silken threads were tubes; and they felt an irresistible desire to enter the shining passages and explore them to the very end; so one day, when the wind was tossing the whole blossoms this way and that, the pollen-grains danced out, and, sailing down on the soft breeze, each one crept in at the open door of a sea-green tube. Down they slid over the shining floors, and what was their delight to find, when they reached the end, that they had all along been expected, and for each one was a little room prepared, and sweet food for their nourishment; and from this time they had no desire to go away, but remained each in his own place, and grew every day stronger and larger and rounder, even as Baby in the cradle there, who has nothing to do but grow.

“Side by side were their cradles, one beyond another in beautiful straight rows; and as the pollen-grains grew daily larger, the cradles also grew for their accommodation, until at last they felt themselves really full of sweet, delicious life; and those who lived at the tops of the rows peeped out from the opening of the dry leaves which wrapped them all together, and saw a little boy with his father coming through the corn-field, while yet everything was beaded with dew, and the sun was scarcely an hour high. The boy carried a basket, and the father broke from the corn-stalks the full, firm ears of sweet corn, and heaped the basket full.”

“O mother!” cried Willie,“ that was father and I. Don’t you remember how we used to go out last summer every morning before breakfast to bring in the corn? And we must have taken that very ear; for I remember how the full kernels lay in straight rows, side by side, just as you have told.”

Now Alice is breaking her threads of silk, and trying to see the tiny opening of the tube; and Annie thinks she will look for the pollen-grains the very next time she goes to the cornfield.

Andrews, Jane. “How the indian corn grows.” Our Young Folks 1, No. 10 (October 1865): 630-31.

Contexts

This story, while not about large-scale agriculture, did come at a time when the strength of farming in several northern states helped buoy U.S. Civil War efforts. At the start of the war, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, and Iowa were seeing incredible growth in crop production, including wheat, corn, and oats. Plentiful domestic food sources were situated in the north, far from the fighting. The abundance also helped maintain U.S. economic importance for Europe as the Confederate States’ cotton exports dwindled. For more information on the economics of U.S. agriculture during the Civil War, see this paper by Emerson D. Fite.

Resources for Further Study

- The National Gardening Association further explains how corn grows.

- Native Seeds/SEARCH shows corn’s integral role in the Three Sisters garden, and Oneida Nation Elder Gail Danforth talks about the Three Sisters:

Contemporary Connections

Organizations like Native Seeds/SEARCH and Native American Food Sovereignty Alliance seek to preserve heirloom seeds and plants as part of larger missions involving food security and sovereignty for Native Americans. Corn is one of the important foods in these efforts, which presents a different philosophy than what makes corn the largest industrial farm product in the U.S. — an industry that supports animal farming, ethanol production, and processed foods.