“A Great Future is Dawning for North Carolina”: Expansion of the WABPS

Just a year after Leah Jones made her rounds to survey the state, there was a marked difference in interest from the public. Viola Boddie travelled extensively during the summers of 1903 and 1904 to speak on behalf of the Association. During one six-week period in the summer of 1903, Boddie spoke to 21 different audiences and organized at least 10 new chapters totaling over 500 members. She reported that the people she spoke with were interested and very responsive to her message. While the work was tiring, she found it rewarding to ignite the interests of people who were willing to put in the work but needed more direction.

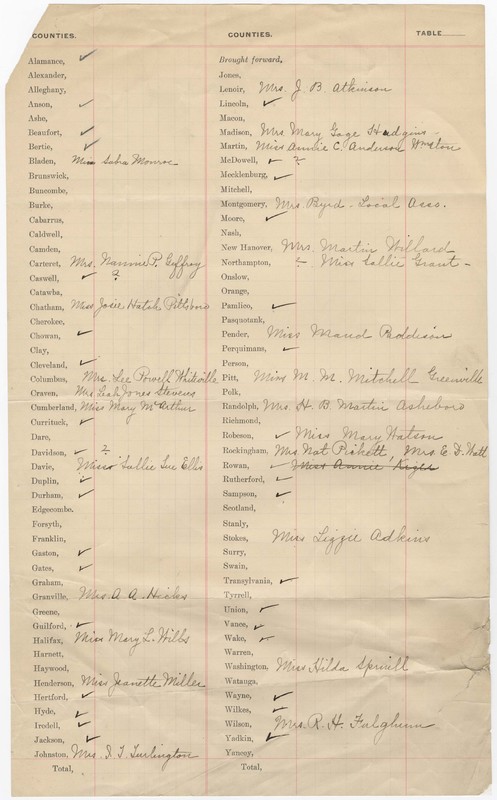

As word about the WABPS spread, dozens of teachers from across the state wrote to the State Association for information on how to start an association of their own. Letters of this sort came from women who were inspired by the work of the WABPS; they often described the small sums of money that their counties invested in education and the dilapidated schoolhouses that they worked in. In order to respond more effectively to these women, and because interest in the organization was growing so rapidly, McIver mailed out questionnaires to counties across the state to gauge the interest and need in creating a WABPS chapter in that area. These questionnaires inquired about what efforts had been made, if the recipient would be willing to establish a chapter (if there wasn't already), and how soon they could begin.

In addition, select women from the State Association also travelled the state speaking with teachers, parents, school board members, and anyone else who would listen about the work that the WABPS was doing. Instead of simply observing schools or taking note of what needed improvement, like they did early on, these women travelled to organize local associations and advocate for reform.

Women like Leah Jones had already stirred the pot by the time Viola Boddie, Edith Royster, and other Field Workers struck out to organize local associations. More often than not, they arrived to find people eager and excited to improve their local schools. The problem, as Boddie noted, was that they needed direction: the women of the WABPS were “glad to get behind the screen of a society to tell some of the teachers of their badly kept school rooms.” As a result, Field Workers held meetings with county teachers and superintendents to establish leaders of each local association. During these meetings, Field Workers would share the most effective ways to improve schoolhouses and engage the community.

Here are some of the practical suggestions that Field Workers made:

- Encourage county officials to propose a special local tax that would allot more funding for the improvement of public schoolhouses. Several counties were able to pass a special school tax of this nature.

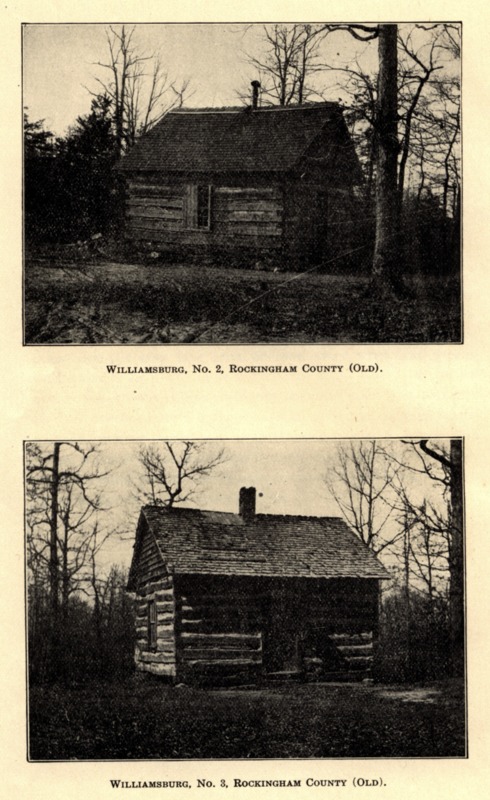

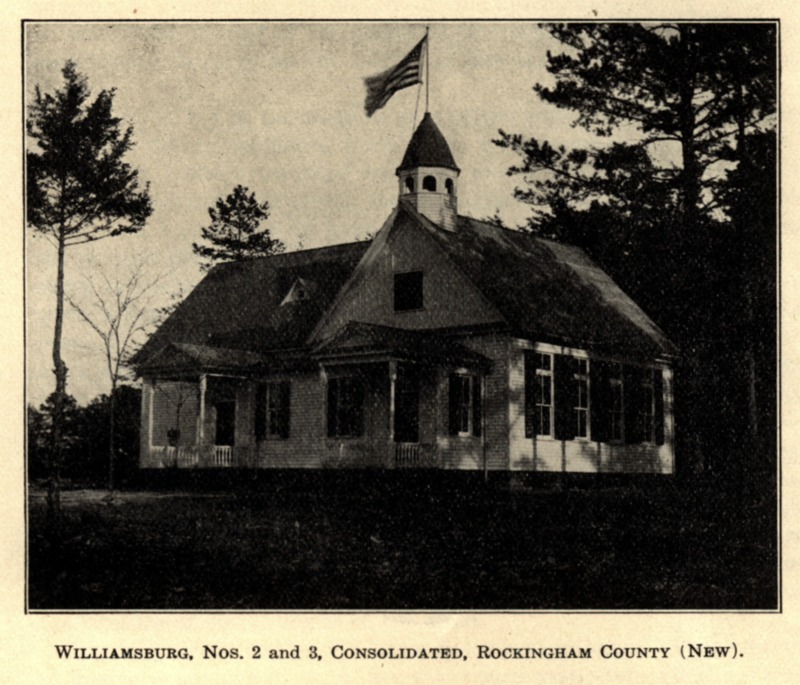

- Consolidate (white) schoolhouses in rural townships so more money could be spent on the improvement of the best available schoolhouse, or the construction of a new one.

- Introduce a bi-annual summer school for teachers. This better equips them for “more proficient teaching.” These were often led by the most experienced teachers in the county and comprehensive exams taken at the end of the summer school showed marked improvement in the preparedness of teachers. To incentivize teachers, the WABPS offered a scholarship to the teacher who makes the greatest improvement to the schoolhouse and grounds. This scholarship would pay all of the expenses for the winner to attend one of the best summer schools in the state.

- Extend the length of the school term.

- Encourage members of the community to support their local organization through donations of funding, labor, or supplies.

By 1912 there were over 70 county and local associations working hard to improve their teachers, their curriculum, and their schoolhouses.

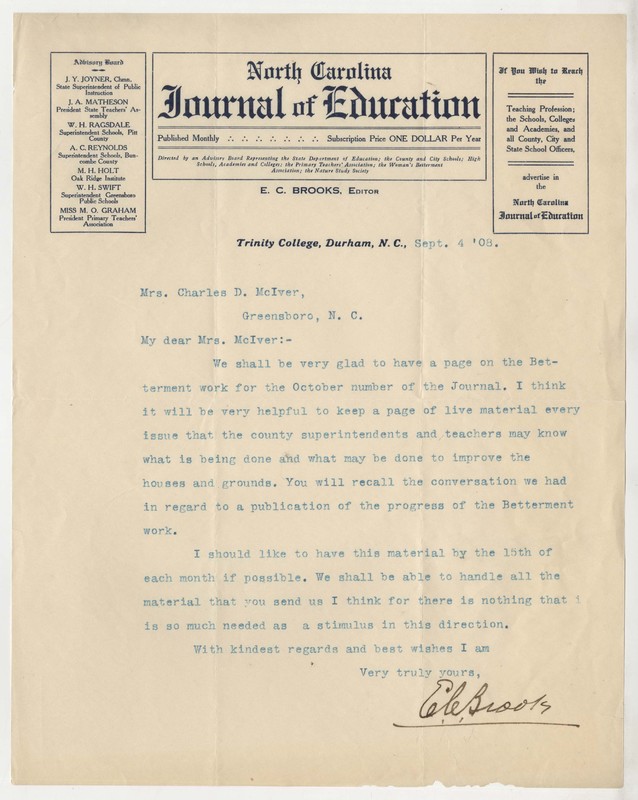

While the women of the Executive Committee worked hard to connect with other teachers and school officials across the state, they also employed the efforts of any person or group who were willing to advocate for their cause. Local businessmen offered free pamphlets on Ideal Public Schools and How to Set out Shrubbery. The head of The Youth’s Companion periodical distributed thousands of pamphlets titled "Free Public Education" to share the need for reform, and to publicize the work of the WABPS. The same paper also donated patriotic photos to be hung in schoolhouses across the state, as did local photography companies. Mr. O. J. Kern, Illinois’ State Superintendent of Public Instruction, sent numerous suggestions on the improvement of school houses and grounds. Editor Clarence Poe, of The Progressive Farmer, and E. C. Brooks, of the North Carolina Journal of Education, offered to publish articles on Betterment work.

Scroll through Andrew S. Draper's pamphlet to see diagrams of the ideal public school lot and landscaping.

In 1908, the Southern Historical Publication Society wrote Mrs. McIver to gather information about the WABPS. The editor was planning a book on the history of the southern states, and wanted to discuss the WABPS in a chapter on womens' part in the educational progress of the South. In 1903, the Southern School and Home Teachers’ Agency wanted to feature the WABPS in a special edition of their publication. They, like the Southern Historical Publication Society, wanted to highlight the association in an article about the work of womens' clubs as auxiliary educational organizations.

Additionally, many regional and county newspapers established a regular column on the work of their local association. The information for these columns was typically supplied by the president of the local association and were generally more detailed than what was published in journals or periodicals.

Several representatives from the State Association were sent out to educational conferences across the South. In 1909, Mrs. McIver gave a report of work done in North Carolina during the opening session of the Southern Educational Conference. Betterment workers from all of the southern states held daily meetings during the conference to discuss the work they’ve done and the work still needed. Aside from meeting with teachers and school officials, women of the WABPS also addressed audiences across the state, from university commencements to Daughters of the Confederacy meetings. During these talks, WABPS representatives spoke to the need for reform and the state of education in North Carolina.

From 1902 to 1909, the Women’s Association for the Betterment of Public Schoolhouses grew exponentially. The young women from Greensboro’s State Normal and Industrial College couldn’t have known the reach that their organization would have. In less than a decade, the women of the WABPS had impacted every aspect of life for teachers and schoolchildren across the state and a new standard had been set for public schoolhouses.